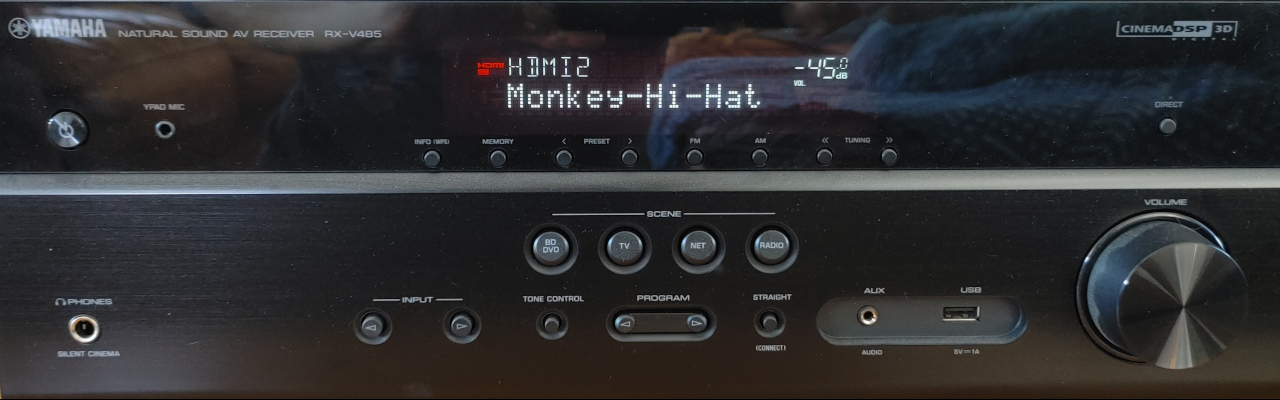

Monkey Hi Hat and the Eyecandy Library

An audio texture library for music visualization.

Last week I posted a short article, Introducing the Monkey Hi Hat Music Visualizer. The application and supporting utilities rely upon some interesting libraries and technologies that I want to write more about. This is the first of several articles about those. It discusses my .NET6 Eyecandy library, which handles the hard work of converting audio data to information that can be fed to OpenGL graphics shaders. This is a fairly complex system, so the library itself will span a couple of articles.

Back in the 1990s and 2000s, the MP3 file format was a new and popular way to collect, share, and listen to music. Around that time, everyone was using the wildly successful music player called WinAmp, and it supported audio visualization plugins – programs that displayed colorful, abstract graphics synchronized to whatever music was being played. (Some people may recall that the XBox, Xbox360, and the original Playstation had built-in visualizers, and even Windows Media Player briefly supported them, but nothing ever approached WinAmp’s dominance or quality. And wow, does YouTube compression suck for this type of content!)

Back then, music visualizers were popular for simple desktop use, or big-screen use at parties, or even as backgrounds at clubs and DJ events. I remember one trip to Miami in the mid-2000s when I counted six clubs in a row projecting music visualizations on the walls of their courtyards and streetside facades along A1A through South Beach. I recognized most of them as WinAmp plugins.

I’ve been interested in computer graphics for as long as they’ve been available on consumer-grade hardware. When I was a kid, I regularly entered little graphics routines in the monthly Soft Sector Magazine one-liner contests. Over ten years ago, I played around with Direct3D, then got into XBox programming via the XNA program. Later, my wife and I dabbled in more modern XBox programming via Unity, and that’s when I really got my feet wet with shader programming (albiet the Microsoft HLSL dialect, rather than OpenGL’s GLSL, but they’re pretty similar.)

Fast forward to the 2020s, and the MP3 format isn’t so popular any more (although I still have 45,000+ of them ripped from our CD collections). Now streaming music is what everyone uses. I was a paying subscriber to Pandora before Sony / SirusXM bought them and destroyed their excellent “music DNA” system. Now we use Spotify, like practically everyone else.

But I missed music visualizers (aka viz). It was time to write my own. How hard can it be?

Why is Everything a Web App?

Thanks to my interest in graphics, I’d long been aware of the GPU-melting fragment shaders (aka pixel shaders) available through the Shadertoy website. Some of those are audio-reactive, which were only technically interesting to me because the site primarily relies on single-track SoundCloud clips. (In recent years, SoundCloud has added playlist support, but I’m not sure if Shadertoy supports those – the handful I tried wouldn’t load.)

Recently, my wife discovered VertextShaderArt (VSA) which is sort of interesting because it’s driven by the other major half of the shader pipeline – vertex data, rather than frag data. The data itself is interesting too, being just a stream of integers (not representing geometry or any other specific data). This one does have the advantage of SoundCloud playlist support.

But these sites are limited. While they have cool things to see, it gets a little dull watching just one viz. Also, WebGL performance is relatively poor, and over time the browsers themselves tend to crash. Neat stuff, often impressive, but “not the droid I’m looking for.”

I should also mention an important third example, which is ButterChurn. Although it isn’t readily open to user-written creations like Shadertoy and VSA are, and content isn’t based on a standard like the GLSL shader langage, it’s notable because it seeks to reproduce the famous MilkDrop WinAmp viz plugin content from 20+ years ago. Unlike the other sites, it does run through a list of different viz routines, and like MilkDrop, it also mixes and overlays them, sometimes producing truly stunning effects (unfortunately, a few of them are also boring or just plain ugly, but mostly it’s pretty interesting). Sadly, it also locks up or crashes pretty regularly – much more often than the other two.

Shadertoy and ButterChurn also both allow for microphone input to viz routines (instead of SoundCloud), and with a little effort, it turns out you can set up a loopback arrangement – anything playing through your speakers also gets fed into the audio recording system as if a microphone was picking it up. And in fact, this is the basis for the way Eyecandy and Monkey Hi Hat obtain streaming audio data…

Audio Data: Then and Now

I’ve already spent a lot more time in this article meandering down Memory Lane instead of talking about the Eyecandy library, so suffice to say the older systems like WinAmp and MilkDrop had to provide their own audio interception and representation techniques, and “in the old days” they also didn’t have fancy 3D APIs available like D3D or OpenGL for the graphics output. Some of the techniques are probably useful (like beat detection), but the specific code and processing is markedly different.

Today, sites like those listed in the previous section rely on shaders using the OpenGL-based WebGL graphics APIs, and audio data is translated into bitmap data, which are presented to the shaders as texture data.

This might sound strange at first – texture data commonly means graphical bitmaps, but in the world of shaders, that’s a historical artifact. Textures are regularly employed as general-purpose data-transfer buffers for all kinds of data – shadow data, surface data (such as “bump maps”), and arbitrary application-specific data. I once wrote a program which encoded a strategy war game’s map border data into the red channel of a bitmap, player data into the green channel, and special-effects data (used to make the borders glow) into the blue channel. One bitmap, three types of completely unrelated data.

That’s what happens with audio data in these programs. There are three main categories of data:

- Wave audio (pulse-code-modulated, aka PCM)

- Frequency (decibels and magnitude)

- Volume (primarily root-mean-squared, aka RMS)

You can read more about each of those on the How It Works wiki page at the Eyecandy repository.

The texture representations of that data is available in seven formats, each identified by the names of the classes that process and manage the data:

AudioTextureWaveHistoryAudioTextureVolumeHistoryAudioTextureFrequencyDecibelHistoryAudioTextureFrequencyMagnitudeHistoryAudioTexture4ChannelHistoryAudioTextureWebAudioHistoryAudioTextureShadertoy

In the next article, I’ll get into the details of how audio data is represented by these classes. For now, we have to talk about system configuration.

Capturing Audio Playback

All the details of configuring your system is in the Monkey Hi Hat Windows or Linux Quick Start wiki pages. I should note that the Linux instructions were created using a 32-bit Raspberry Pi 4B. While the 1.x versions of Eyecandy and Monkey Hi Hat support the Raspberry Pi, in the future I’ll be dropping that support due to GPU limitations. However, general Linux compatibility is something I’m interested in retaining, and at a minimum, I’ll try to ensure everything works via Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL).

At a high level, you need to set up “loopback” audio. In theory, you could do this with a physical cable, which is where the term comes from: plug the speaker output into the microphone input and you’re off to the races. But since this is the 21st century, we’ll do it with software.

On the Linux side, the steps are more complicated but everything is probably already available within the OS. For Windows, you will have to install a loopback driver. I use a “donation-ware” product from VB-Audio called Cable, and I found another product for sale which I didn’t try called Virtual Audio Cable.

Once the configuration is done, your computer will offer an input (recording) device which represents the same data currently being played through speakers or some other output device.

This is a big improvement over “the old days” – you aren’t tied to MP3 files or a particular player. The program can intercept audio from any source: movies, videos, streaming audio playback, web browsers, you name it.

I assume readers of my blog will already have .NET installed, but the .NET6 runtime is the other must-have configuration item required by Eyecandy. It’s also highly recommended to install the OpenAL Soft drivers on top of the older, no-longer-maintained OpenAL drivers. All of these points are also detailed in the Quick Start wiki pages.

General Library Usage

Once again I will recommend the repository’s wiki pages, specifically Windowed Usage and Audio-Only Usage, but as those topics suggest, the library supports at least two usage scenarios.

Audio-only usage involves pointing the library’s AudioCaptureProcessor at an audio input device, defining a callback for notification when new audio data is available, and reading and using the data however you wish.

Windowed-usage assumes you’re interested in the viz aspects of the library. You’ll probably want to subclass the BaseWindow helper class (although this isn’t a requirement), and use the AudioTextureEngine to define the kinds of audio texture data you need.

The library offers a demo project which contains a variety of utilities and samples that employ each of these requirements.

Library Structure

If you dig into the eyecandy directories at the source repo, you’ll find that the library code is organized under four directories:

Audiois where most of the work is done – audio capture and managing the processing of audio data into OpenGL textures.AudioTexturescontains the base class and the individual audio texture classes mentioned earlier in this article. Each of these do the actual conversion work when new audio samples are available. I have thought about offering plugin support, but I’m not sure there are many other rational interpretations of the audio data to make the effort worthwhile. If you have ideas, please definitely drop me a note. A PR to create a new class might make more sense.Utilsis where enumerations are defined, error logging is handled, and the library’s two configuration classes are defined.Visualholds the library’s two helper classes – the windowing base class, and a shader-management class.

Dependencies

In addition to the source code organization, the library uses three library packages:

- OpenTK is the real star of the show. The OpenTK library provides high-quality (but lightweight!) wrappers around the OpenGL and OpenAL (audio) APIs. It also wraps the GLFW API, which provides OpenGL-based cross-platform windowing and input support (keyboard, mouse, etc).

- FftSharp is a fast, simple, handy utility-library for performing Fast Fourier Transforms. These are necessary to generate frequency data (decibels and magnitude).

- The standard Microsoft.Extensions.Logging library is also used. Wiring this up is completely optional, but if you do, I very strongly recommend the excellent Serilog libraries. Monkey Hi Hat has a very basic zero-configuration LogHelper class which makes basic Serilog integration totally painless.

Conclusion

This article was a fairly high-level introduction to the Eyecandy library. In the next installment, I’ll explain what the library produces – the raw audio data, as well as the texture output.

Meanwhile, if this interests you, pull a copy down, build it, configure your system according to the wiki instructions, and check out the demo program.

Comments