Architecture of the Eyecandy Library

A quick look at how the Eyecandy audio texture library works.

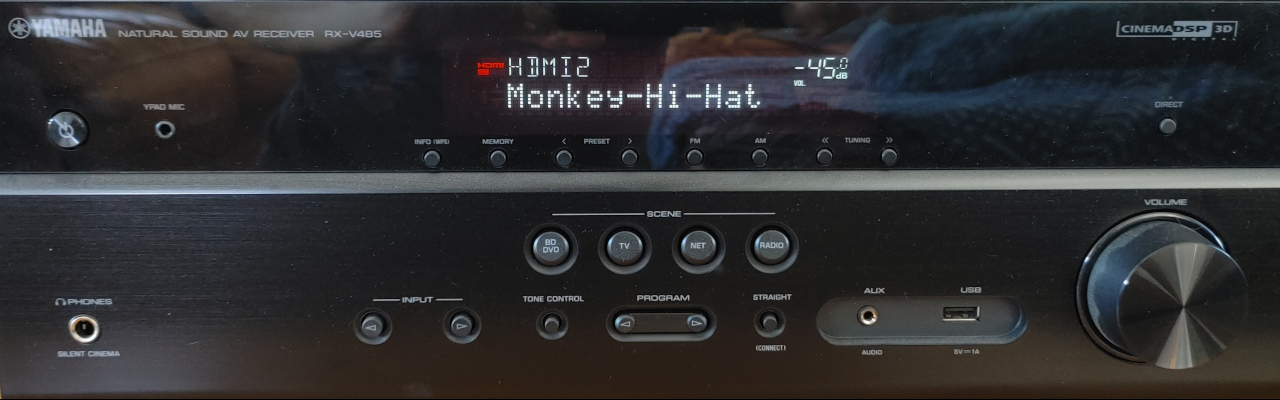

Welcome to another installment in a series of articles about my Monkey Hi Hat music visualizer application, and the supporting libraries, applications, and content. You may wish to start with the earlier articles in this series:

- Introducing the Monkey Hi Hat Music Visualizer

- Monkey Hi Hat and the Eyecandy Library

- Monkey Hi Hat and Eyecandy Audio Textures

Today I’m going to quickly cover the general architecture of the Eyecandy library. When I decided to write a music visualizer, I had no idea how any of this actually worked. It took about a month to create mostly-working code, at which point I threw it all away and started writing Eyecandy from scratch. That took about two months, and then I spend another month writing Monkey Hi Hat, which resulted in several point releases of Eyecandy.

However, architecturally-speaking the library is pretty simple. All of the heavy-lifting is orchestrated by the AudioCaptureProcessor and AudioTextureEngine classes.

Audio Capture

As earlier articles and the wiki notes, the library can be used for audio capture only, although that’s so easy to do with off-the-shelf OpenAL (or more likely OpenAL-Soft), there’s not much point in using Eyecandy for that. The big difference between typical OpenAL capture code and the Eyecandy approach is that audio is processed on a separate thread. This can be a little bit tricky since neither OpenAL nor OpenGL are particularly friendly to multi-threaded code.

At a high level, the AudioCaptureProcessor class constructor requires an EyeCandyCaptureConfig object, which defines things like the audio sample size, normalization factors, and other things which will probably never need to be adjusted from their default values. (Indeed, I still haven’t gotten around to supporting Monkey Hi Hat config-file entries to alter these defaults.)

The constructor initializes a few buffers, makes some private copies of certain fields which will need to be read by the separate audio-capture thread, and that’s about it.

There is also an AudioProcessingRequirements property which the library consumer must keep up-to-date. This is just a set of flags which controls the different post-processing options (for example, whether the consumer needs RMS volume data).

The library consumer uses Task.Run to invoke the Capture method on a separate thread. Capturing is terminated via CancellationToken and the method requires a callback Action which is invoked when the OpenAL library has enough audio sample data available to fill the buffer (which, by default, is short[1024]).

Before the callback is invoked, a ProcessSamples method is called. This reads the samples, performs various required calculations like generating RMS volume or FFT decibel-scale frequency data, and the results are also stored into buffers.

For thread-safety purposes, the various buffers are grouped into the AudioData class, and two of these are swapped back and forth using Interlocked.Exchange ensuring that the publicly-accessible buffers will never be accessed by the background thread. The Timestamp property on that class can be used by consumers to determine when the buffers were updated.

Once the updated AudioData has been flipped to the publicly-accessible side, the consumer’s callback function is invoked to do something with the data. It’s important to remember that this callback will also be running on the background thread doing the capture.

Even though it runs on a background thread, checking for audio sample data availability is still a polling loop. That led to a study of the various delay, sleep, and wait options in .NET, and there are many of them. Also, in many cases passing a 0 or 1 value often has special meaning. Originally my code called Thread.Yield which works, but later on when Monkey Hi Hat was useable, I returned to this area and started reviewing the frame-rate impact of the various options. I finally settled on Thread.Sleep(0) which cedes control to any thread of equal-priority, yet produces the best frame rate out of all the options. While I did re-run each test many times, I didn’t take any special measures to optimize testing conditions; I tested while streaming Spotify, with several copies of VS running, god-only-knows how many Firefox processes loaded, and so on. The comments in the code (and below) document my findings, noting the approximate average frame rate, as well as what my research indicated the different calls do behind the scenes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

// Relative FPS results using different methods with "demo freq" (worst-performer).

// FPS for Win10x64 debug build in IDE with a Ryzen 9 3900XT and GeForce RTX 2060.

Thread.Sleep(0); // 4750 cede control to any thread of equal priority

// spinWait.SpinOnce(); // 4100 periodically yields (default is 10 iterations)

// Thread.Sleep(1); // 3900 cede control to any thread of OS choice

// Thread.Yield(); // 3650 cede control to any thread on the same core

// await Task.Delay(0); // 3600 creates and waits on a system timer

// do nothing // 3600 burn down a CPU core

// Thread.SpinWait(1); // 3600 duration-limited Yield

// await Task.Yield(); // 3250 suspend task indefinitely (scheduler control)

Once the consumer cancels the CancellationToken, the sample polling loop ends and stops capturing. Although my use-case doesn’t work that way, it should be possible to call Capture again as long as Dispose hasn’t been invoked.

Audio Texture Management

For visualization programs, the AudioTextureEngine class coordinates the conversion of audio data to OpenGL textures. The library consumer doesn’t have to deal with the audio capture aspect at all. Like the audio capture class, the constructor requires an EyeCandyCaptureConfig object defining various audio capture settings, and again, the defaults are probably always acceptable.

Although the release-version of the library is v1.x as I write this, the v2 constructor has an interesting OpenGL call querying the maximum number of texture units (there is a simliar value which misleads a lot of people, the number of units individual shaders can access, but that’s not of interest here).

While I don’t intend to get into the nitty gritty details of OpenGL, working with textures is frankly a pain in the ass. You have texture handles which is how you’d work with data in most normal APIs. But OpenGL requires you to go a step further and also assign textures to texture units (TUs), which are apparently the numeric identifiers of memory slots where textures are actually stored. You’d think an API could figure those things out transparently, but 20 years ago some sort of backwards compatibility decision was made that probably seemed like a good idea at the time, and today we’re still paying the price.

Each GPU and driver combo supports a limited number of TUs. In the early days it was commonly just the required minimum 16 units, but modern hardware goes well beyond that. The total number reported by my card is 192.

Because I intend to support multiple-pass shaders, post-processing effects, and similar features, and the framebuffers involved also need TU assignments, and because Eyecandy currently only supports a small number of audio texture types, I decided to hard-assign the TUs internally.

The v1 releases require the library consumer to manage TU assignments, although this just amounts to a number in the visualizer config file; in v2 that number just becomes a config-file indexer and has no bearing on OpenGL API usage. Also, v1 uses the OpenTK / OpenGL TextureUnit enums, but v2 uses integers. I have since learned that nobody uses the enums, they only support 32 TUs, after which the OpenGL spec people gave up and decided numbers were easier. One quirk: if an API requires the enum, you have to add the integer to TextureUnit.Texture0 because that’s some oddball number – but you can “legally” go beyond the defined Texture32 enum all the way to your card’s upper limit. The v2 library now stores all TUs as int.

To minimize collision possibilites, TU numbers are assigned to audio texture types descending from the maximum value. Since the library currently has seven audio textures available, this means texture units 189 through 191 should be considered “reserved” for Eyecandy use. TU zero through 188 are available for use by the library consumer. In the case of Monkey Hi Hat, I don’t imagine more than eight or ten might be used in extreme cases.

The library consumer indicates which audio textures are needed by calling Create<AudioTextureType> and specifying the shader uniform name. Nothing is returned, audio texture management is 100% internal to the library. From there, it’s a simple matter of calling BeginAudioProcessing, then in the library consumer’s render loop, call UpdateTextures and SetTextureUniforms.

The UpdateTextures method exits immediately if the audio data hasn’t been updated since the last call (as long as all the textures have been updated at least once, which ensures the buffers are fully initialized). Otherwise it loops through whatever textures were requested by calls to Create and those objects are each invoked to update themselves. More on that in the next section.

The call to SetTextureUniforms requires a reference to the active Shader object because, of course, that’s where the uniforms are defined and used.

The only real quirk is shutdown. The async EndAudioProcessing is the ideal way to cleanly terminate processing, but the OpenTK GLFW windowing system doesn’t have async events. So we’re stuck making a sync-over-async call via EndAudioProcessing_SynchronousHack which is unfortunate, although in practice (after hundreds of hours of runtime) it hasn’t been an issue.

Under the hood, BeginAudioProcessing just uses Task.Run to call the AudioCaptureProcessor.Capture method described in the previous section. The audio sample callback is ProcessAudioDataCallback which just loops through the currently-loaded audio texture objects and invokes their UpdateChannelBuffer methods.

This brings us to the texture classes themselves.

Audio Texture Generation

Each audio texture derives from the abstract AudioTexture class, where most of the work is done. Since the class has many settings and requirements, and a some of those have to be defined during construction by the implementation (so that buffers can be sized accordingly, for example), a factory method is used to keep construction and initialization internal to the base class.

Generally speaking, a texture implementation only has to specify the pixel width, row count, and the audio data type(s) the class uses, plus an implementation of the abstract UpdateChannelBuffer method which reads the audio buffers and writes pixel color channel values to the texture buffer. For history textures, a ScrollHistoryBuffer method is provided.

Because these calls are in response to the audio capture background thread, it is necessary to use a lock section around all access to the texture buffer to guard against access requests from the UI thread.

Most of the textures are quite simple. AudioTextureVolumeHistory only has six lines of code (ignoring comments, method declarations, etc.). Only AudioTextureShadertoy has any real logic inside owing to the fact that Eyecandy uses textures which are 1024 pixels wide, but Shadertoy only uses the first 512 elements of the 1024 elements of frequency data.

I have considered adding plugin support for additional audio textures, but I’m having a hard time imagining what else might be usefully done with the audio data – and true plugin management is still kind of hairy (although these are extremely simple objects).

Conclusion

And thus concludes the whirlwind tour of the Eyecandy library. There is also a relatively trivial BaseWindow class that handles a few minor UI chores, and the Shader class which just loads, compiles, and verifies vertex and fragment shader source files, and offers some helpful utility functions, but they’re self-explanatory.

In the next installment, we’ll take a look at the Monkey Hi Hat program itself.

Comments