SignOutAsync and Identity Server Cookies

Handling sign-out correctly can be complicated, and the behavior of ASP.NET Core’s SignOutAsync method is not always obvious. We’ll examine one common scenario that can be very difficult to diagnose.

Recently my wife and I began building a service that relies upon Identity Server to authenticate users. In general, the various concerns and edge-cases around login and logout are surprisingly complex topics that I will write more about soon. While planning the account management for the site, we identified a scenario we wanted to support which isn’t available on any site we’re aware of.

Let’s imagine a new service called ChatterBook becomes the next big social media superstar. Your users are clamoring to sign on using their ChatterBook account. You tweak your server’s list of identity providers (IdP) to include your ChatterBook-provided API key, perhaps fiddle with the login page a little, and boom, you’re up and running. Users love it. Soon you have many accounts signing in daily through ChatterBook authentication.

Fast forward a couple of years, and suddenly ChatterBook has gone the way of MySpace, a zombie-service full of outdated content with little or no traffic. Your ChatterBook users are unhappy. Thankfully your service hasn’t become a MySpace graveyard full of <blink> tags and animated GIF backgrounds, but you’ve added the hot new FriendBook login option and your ChatterBook users begin emailing support, asking ask to switch their login to FriendBook without starting over with a new account. Perhaps your users are the holy grail: paid subscribers, whom you really don’t want to blow off by answering that a new login requires creating a brand new account. Even if you’re willing to pay for the overhead of support staff handling the change-overs on demand, it’s a bad user experience and you’ll likely lose users as time goes on.

And there’s the hitch with third-party authentication: How do you let the user migrate their account to a different identity provider?

This article isn’t about solving that problem. It actually isn’t a difficult problem to solve, most sites just ignore it altogether (and I suspect they may not realize the problem exists). This article is about a subtle problem that arose while addressing that requirement.

Identity Provider Migration

Before we talk about the real issue, we’ll quickly review how to solve the IdP-migration problem. Your system will have a database that stores information about the users. In order to support OIDC authentication, you rely on IdP claims to identify the user. In particular, the Subject Id (often just “Subject”) is the unique identifer for that user in the IdP system. You’ll also normally use IdP claims to obtain a user name and email address. The typical model with Identity Server is to also generate a locally-assigned Subject Id that is your unique user identifier. You can’t rely on IdP Subjects across your system because there may be collisions between different IdPs. Identity Server also requires persisting grants to the database, and in the system we’re building, our user store also saves the IdP claims to the database since they can be useful for troubleshooting and support purposes. All of these come into play when migrating an account to a new IdP.

In our system, we have an additional complicating factor: users may also login with a local account (a username-and-password login) rather than selecting a third-party IdP. We decided to support login migration between third-party and local-account IdPs, as well as external-to-external.

The trick to IdP migration is to identify a common factor between the IdPs, and for all practical purposes, that factor will be the user’s email address. Certain standards bodies state that email should not be treated as a unique identifier, but in the real world, if your site doesn’t know your user’s email address, your users probably aren’t doing much that is interesting anyway. Important features like password reset treat email as sufficiently secure and unique, so it’s a pretty safe assumption for IdP migration, too – just be certain your users understand that, as well.

As stated earlier, the solution is simple. When a logged-in user indicates a desire to migrate their account to a new IdP, drop a flag in the database, logout the user, and send them back to the login page. The account is migrated during the new login flow. Somewhere in that process, explain that they need only login with their new IdP, and that both IdPs must reference the same email address. Additionally, the user can cancel this change by logging into the original IdP again.

While processing the login, the new IdP will appear to be a new account. In that case, check the database for a different user with the same email address (something you should guard against anyway), and if that user account has the “migrate” flag (we actually use a CryptoRandom code, an expiration, and some other safety-features), drop the old IdP and substitute the new one, and skip the new-account creation.

Switching from an external IdP to a local account requires an extra step: prompt the user to create a password. We update the account and consider the migration complete at that stage, but logout/login is still required because Identity Server needs to recognize the IdP change, and the login process is the logical place to remove the old IdP claims from the database. The other direction, local to external IdP, works exactly like external-to-external.

As the article title suggests, the problem was related to logging out the user.

A Tale of Two Signouts

Our fledgling client website has two places for signout. One is part of the IdP-migration process described in the previous section. The other is available as soon as the user is authenticated. The page header displays a few account-related options including simple Logout link:

Under the hood, an AccountService object exposes a very simple SignOutAsync method to execute a logout. Both of the signout processes call this same method:

1

2

3

4

5

public async Task SignOutAsync()

{

await httpContext.SignOutAsync("Cookies");

await httpContext.SignOutAsync("oidc");

}

Dead easy, right? And yet, those two simple lines of code hide the subtle and confusing issue we’re here to discuss.

Just about anywhere you look, this is the recommended way to handle ASP.NET Core cookie authentication sign-out (and, obviously, the "oidc" scheme is specifically for OIDC signout). And sure enough, if you click the Logout link in the header, the browser fires the AccountController method shown below and the user is logged out.

1

2

3

4

5

6

[HttpPost]

[ValidateAntiForgeryToken]

public async Task Logout()

{

await acctsvc.SignOut();

}

Here is the confusing part: Although signout worked perfectly from the Logout link in the page header, the user was only temporarily signed out when this Razor Pages postback-handler was executed to begin the IdP-migration process. Notice line 5 in this method and the one above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public async Task<IActionResult> OnPostMigrateAccount()

{

var acct = await acctsvc.GetAccountUser(User);

await acctsvc.ApproveIdpMigration(acct);

await acctsvc.SignOutAsync();

return Redirect(Url.Page("MigrateInstructions"));

}

The details of how that code sets up the IdP migration aren’t important. What matters is that both sign-out processes call that two-line SignOutAsync method, yet only one achieved permanent signout. When the user landed on the MigrateInstructions page, some client-side Razor debug code showed that User.Identity.IsAuthenticated was false. As far as ASP.NET Core’s Identity system servicing the client web app was concerned, the user really was logged out at that point in time.

And yet, clicking the Login button on that page immediately returned the user to the client application’s Index page, and the user was once again fully logged-in. No login page was presented. Similarly, if the user didn’t click the Login button, but instead navigated back to the client app homepage, they were automatically logged back in.

Anyone familiar with the OIDC flow and/or Identity Server will recognize that the user was still logged in on the Identity Server side. When that happens, no login UI is presented. Identity Server recognizes the user and can “restore” their signed-in status automatically. Indeed, we rely upon this behavior in my earlier article, Persistent Login with IdentityServer4 to keep a user logged in across multiple sessions.

The mystery isn’t why the user is logged in again – it’s why they weren’t logged out on both servers regardless of which bit of code called our two-line sign-out method. After all, the Login link in the header of the same page (the one that handles IdP migration) works reliably every time, and they’re both calling the same AccountService method.

The Struggle is Real

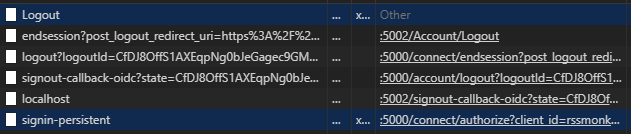

A quick trip through Chrome’s F12 network log proved the sign-out code behaved differently depending on where it was called from. With the header Logout link, the traffic for a working, permanent sign-out looked something like this (with non-auth requests like images or scripts filtered out). Port 5000 is Identity Server, port 5002 is the client website.

It begins with the HTTP POST to the Logout action in AccountController. As we saw earlier, that doesn’t do anything but await the two-line AccountService sign-out method. Those calls to HttpContext.SignOutAsync result in the OIDC endsession flow. The final two requests are the client site’s attempt to restore a persistent login, as described in the earlier article. This attempt fails because the user is signed out in Identity Server – exactly what we’re trying to achieve here.

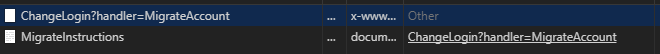

However, sign-out from the OnPostMigrateAccount handler tells a very different story:

There is only the HTTP POST to the OnPostMigrateAccount hander followed by the final redirect to the migration instructions. For some reason, HttpContext.SignOutAsync removed the local cookies (which is why the Razor debug code shows User.Identity.IsAuthenticate is false on that page), but seems to have ignored the OIDC endsession flow. As soon as we do anything that checks Identity Server for a persistent login, the user’s login is restored.

Different behavior based on where the call originated? Perplexing.

Behavior Modification

It’s worth noting there are many questions that seem to relate to this problem on StackOverflow, GitHub issues, and other developer Q&A sites. Worse yet, there are few correct answers (actually, none that I could find). Most people either brute-force attack their client site cookies by arbitrarily expiring them (basically forcing login failures), or they write code to explicitly redirect the browser to the OIDC endsession URI. Neither of these approaches are correct.

The clue came from a comment posted on GitHub back in 2015 by Microsoft’s Hao Kung, a developer who works on ASP.NET Identity:

The new behavior is sign out redirects immediately rather than later so before the sign out would win. Now the redirect to home wins which is why you need to return empty result.

Apparently someone at Microsoft decided to change how SignOutAsync works. In the old days (2014), the endsession endpoint would be called every time, guaranteed. But now it only happens if there is no other output within the context of the same Task.

As far as I can tell this change is not documented anywhere.

When Hao Kung says one value or another “wins,” that really means the last redirect that is issued is the one that will actually be sent to the client. HttpClient.SignOutAsync ends with redirect that would kick off the OIDC endsession flow. However, our OnPostMigrateAccount page handler “overwrites” this redirect with a different redirect to the MigrateInstructions page. The endsession redirect never happens.

OIDC Sign Out Callback

Unfortunately, we do need control over where the user lands after logout, so Hao Kung’s recommendation to simply return an empty result isn’t the end of our troubles. Luckily the OIDC standard has a simple solution.

HttpContext.SignOutAsync has an overload which accepts an AuthenticationProperties object, and that class has a RedirectUri property. When that URI is provided, it overrides the default URI defined in the Identity Server client configuration.

We change our AccountService.SignOutAsync to accept an optional redirectUri parameter (optional because a use-case such as the header Logout link doesn’t need to specify a redirect URI):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public async Task SignOutAsync(string redirectUri = null)

{

var props = (redirectUri is null) ? null : new AuthenticationProperties()

{

RedirectUri = redirectUri

};

await httpContext.SignOutAsync("Cookies");

await httpContext.SignOutAsync("oidc", props);

}

Then, instead of issuing an IActionResult redirection from the OnPostMigrateAccount handler, we change the signature to a Task with no underlying return type, and pass the target URL to the AccountService sign-out method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

public async Task OnPostMigrateAccount()

{

var acct = await acctsvc.GetAccountUser(User);

await acctsvc.ApproveIdpMigration(acct);

await acctsvc.SignOutAsync(Url.Page("MigrateInstructions"));

}

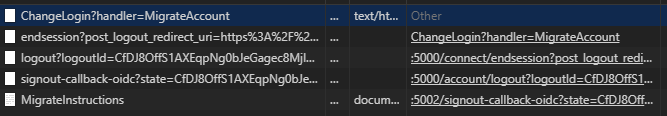

Running the code verifies this works as expected – the user is logged out and stays logged out. Returning to the browser network traffic viewer shows the OIDC endsession request that triggers signout on Identity Server, followed by a redirection back to the client site’s MigrateInstructions page:

Problem solved.

Conclusion

When troubleshooting Identity Server or other OpenId Connect problems, it’s critical to understand what is supposed to be happening behind the scenes, then verify that’s actually happening. Unfortunately, this rather major change to ASP.NET Core’s signout behavior was not just made quietly, and seemingly without discussion, it isn’t even documented anywhere that I could find. To me, this is another failing of the “convention over configuration” and “it just works” mentalities driving recent ASP.NET development. Sometimes it just doesn’t work and one can lose a great deal of time trying to figure out which piece of the puzzle is responsible.

Fortunately, this riddle had a simple and effective solution. Next time we’ll take a big-picture look at authorization concerns and their related flows – less about the code and more about the processes.

Comments