Persistent Login with IdentityServer4

Users expect a persistent login to “just work” as soon as they reach the website, and landing pages rely on user authentication to vary what the user sees (“Register / Login” versus “Account / Logout”). This is relatively simple to add to an IdentityServer4 client and id provider.

In the article IdentityServer4 Without Entity Framework, we created a client web application that triggered the Identity Server login process by adding an [Authorize] attribute to the page model for the About page, and we altered the external login cookie for a long-duration expiration (compared to IdentityServer4’s default setting of session expiration).

This is a form of persistent login. When authorization is required, as long as the user still has a valid login cookie on Identity Server, the user will be transparently authorized in the client application for the remainder of the session.

However, the lead paragraph describes an edge-case. What if your landing page should recognize authorized users who signed in during some previous, separate session, but also allow anonymous users – either new users without an account, or users whose previous login has expired?

Fortunately, this is easy to add. We’ll build on the IdentityServer / client app projects used in earlier posts – specifically starting from the code from HTTPS in IdentityServer4 and ASP.NET Core 2. Files changed or added in this article can be found in this repository.

Create the Problem

The earlier article didn’t have any landing-page code that responded to login status.

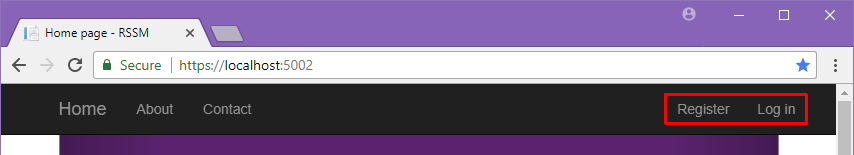

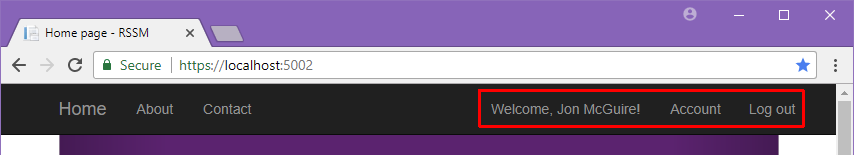

Anonymous users will see registration and login links when they navigate to the landing page.

However, when a properly authenticated user loads the same page, they will be welcomed with their name, a link to manage their account, and another link to log out of the site.

To accomplish this, we’ll borrow from Microsoft’s ASP.NET Identity template project by loading a Razor partial into the client application’s layout template. Open _Layout.cshtml and locate the Home, About, and Contact links. Add the partial reference as shown.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

<div class="navbar-collapse collapse">

<ul class="nav navbar-nav">

<li><a asp-page="/Index">Home</a></li>

<li><a asp-page="/About">About</a></li>

<li><a asp-page="/Contact">Contact</a></li>

</ul>

<!-- add this -->

@await Html.PartialAsync("_LoginPartial")

</div>

Next, create a file named _LoginPartial.cshtml in the client app’s Pages folder containing the following code. (This isn’t exactly what you’d find in an ASP.NET Identity template project since we aren’t using Microsoft’s Entity Framework Identity assemblies.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

@using ClientWebApp.Services

@inject IAccountService AccountService

@if(AccountService.IsSignedIn(User))

{

<form asp-controller="Account" asp-action="Logout" method="post" id="logoutForm" class="navbar-right">

<ul class="nav navbar-nav navbar-right">

<li><a asp-page="/Account/Manage/Index" title="Manage">Welcome, @AccountService.GetUserName(User)!</a></li>

<li><a asp-page="/Account/Manage/Index" title="Manage">Account</a></li>

<li><button type="submit" class="btn btn-link navbar-btn navbar-link">Log out</button></li>

</ul>

</form>

}

else

{

<form asp-controller="Account" asp-action="Login" method="post" id="loginForm" class="navbar-right">

<ul class="nav navbar-nav navbar-right">

<li><a asp-page="/Account/Register">Register</a></li>

<li><button type="submit" class="btn btn-link navbar-btn navbar-link">Log in</button></li>

</ul>

</form>

}

Login and Logout

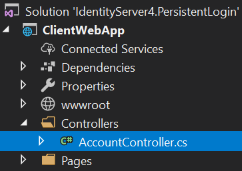

You may have noticed the login/logout forms in _LoginPartial point to asp-controller="Account". Registration and account management are beyond the scope of this article, but it’s easy to make the Login and Logout links functional. Add a new top-level Controllers folder to your client app, then create a new AccountController class.

Change the code in AccountController as shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

using System.Threading.Tasks;

using IdentityModel.Client;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Authentication;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

namespace ClientWebApp.Controllers

{

public class AccountController : Controller

{

[HttpPost]

[ValidateAntiForgeryToken]

public IActionResult Logout()

{

return new SignOutResult(new[] { "oidc", "Cookies" });

}

[HttpPost]

[ValidateAntiForgeryToken]

public async Task Login(string returnUrl = null)

{

// clear any existing external cookie to ensure a clean login process

await HttpContext.SignOutAsync("oidc");

// see IdentityServer4 QuickStartUI AccountController ExternalLogin

await HttpContext.ChallengeAsync("oidc",

new AuthenticationProperties() {

RedirectUri = Url.Action("LoginCallback"),

});

}

[HttpGet]

public IActionResult LoginCallback()

{

// TODO read user data by subject id

return RedirectToPage("/Index");

}

}

}

Account Service

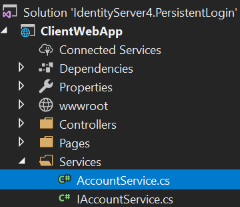

A website that uses Microsoft ASP.NET Core Identity Entity Framework relies upon two services: SignInManager and AccountManager. We don’t necessarily need everything those services provide, so we’ll just create a single service. First, create the interface so we can register it for dependency injection. Create a top-level folder named Services, and inside that add a class file named IAccountService and another named AccountService.

The IAccountService interface only requires two methods.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

using System.Security.Claims;

namespace ClientWebApp.Services

{

public interface IAccountService

{

bool IsSignedIn(ClaimsPrincipal principal);

string GetUserName(ClaimsPrincipal principal);

}

}

The correpsonding AccountService class is also simple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Http;

using Microsoft.IdentityModel.Tokens;

using System;

using System.Linq;

using System.Security.Claims;

namespace ClientWebApp.Services

{

public class AccountService : IAccountService

{

private HttpContext httpContext;

public AccountService(IHttpContextAccessor diContextAccessor)

{

httpContext = diContextAccessor.HttpContext;

}

public bool IsSignedIn(ClaimsPrincipal principal)

{

return principal?.Identities != null &&

principal.Identities.Any(i => i.AuthenticationType == TokenValidationParameters.DefaultAuthenticationType);

}

public string GetUserName(ClaimsPrincipal principal)

{

string name = principal.FindFirstValue(ClaimTypes.Name);

if(String.IsNullOrEmpty(name))

name = principal.FindFirstValue("name");

// TODO load persisted user data via subject id, if needed

return name;

}

}

}

The IsSignedIn method looks for a recognized authentication process. After a successful third-party authentication through IdentityServer4, this will contain the value AuthenticationTypes.Federation. Oddly, this seems to originate from DefaultAuthenticateType from this Azure Active Directory assembly, which appears to be the only Microsoft repository where that specific string appears. For any real application, you should probably test the contents of this property after authentication against all of your supported identity providers.

As indicated by the TODO comment in the GetUserName method, in a real application, this service would probably be enhanced to retrieve and cache the user’s persisted data from the database, most likely by querying agianst the subject id (“sub”) claim.

Finally, we must register the service for dependency inject. Open the client app’s Startup.cs class and add these using statements at the top of the file.

1

2

3

using ClientWebApp.Services;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Authentication.OpenIdConnect;

using IdentityModel;

Now add the following to the very end of the ConfigureServices method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

// other config code omitted

// add this

services

.AddScoped<IAccountService, AccountService>();

}

The “scoped” service lifetime matches the lifetime used by SignInManager and AccountManager in ASP.NET Core Identity.

Persistent Login Handler

In the earlier article, the AddAuthentication configuration established cookie-based authentication using an AddOpenIdConnect scheme named oidc as the default login process. We’re going to expand on that by adding a second AddOpenIdConnect scheme named persistent. It is exactly like the scheme named oidc except it defines an alternate sign-in endpoint URI (the redirect target after IdentityServer4 completes the login process), and adds a couple of event-handlers. Add the new scheme as shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

// default scheme from the earlier article

// normal OIDC login flow (via Login button or [Authorize] attrib)

.AddOpenIdConnect("oidc", options =>

{

options.SignInScheme = "Cookies";

options.Authority = "https://localhost:5000";

options.RequireHttpsMetadata = false;

options.ClientId = "mv10blog.client";

options.ClientSecret = "the_secret";

options.ResponseType = "code id_token";

options.SaveTokens = true;

options.GetClaimsFromUserInfoEndpoint = true;

})

// add this

// attempt to re-establish persistent login for new session (see IndexModel.OnGet)

.AddOpenIdConnect("persistent", options =>

{

options.CallbackPath = "/signin-persistent";

options.Events = new OpenIdConnectEvents

{

OnRedirectToIdentityProvider = context =>

{

context.ProtocolMessage.Prompt = OidcConstants.PromptModes.None;

return Task.FromResult<object>(null);

},

OnMessageReceived = context => {

if(string.Equals(context.ProtocolMessage.Error, "login_required", StringComparison.Ordinal))

{

context.HandleResponse();

context.Response.Redirect("/");

}

return Task.FromResult<object>(null);

}

};

// the rest is identical to the interactive scheme named "oidc"

options.SignInScheme = "Cookies";

options.Authority = "https://localhost:5000";

options.RequireHttpsMetadata = false;

options.ClientId = "mv10blog.client";

options.ClientSecret = "the_secret";

options.ResponseType = "code id_token";

options.SaveTokens = true;

options.GetClaimsFromUserInfoEndpoint = true;

});

CallbackPath is the after-sign-in redirect URI.

The OnRedirectToIdentityProvider event handler changes the Prompt option to the value none, then allows the login flow to proceed. In the OpenId Connect world, the none value tells the OIDC server to fail silently if there is no valid login cookie available (either because the user hasn’t logged in yet, or because the existing login has expired). This is the key to avoiding the presentation of a login prompt to a genuinely anonymous user trying to reach our authentication-aware landing page.

When there is no login presented, Identity Server sends back login_required in the OIDC protocol’s Error field. The OnMessageReceived event-handler watches for this and simply redirects the user back to the landing page.

Triggering Re-Authentication

By itself, the preceding code does nothing. We need more code to tell ASP.NET Core to ask Identity Server to authenticate the user. That happens in the page model code for the Index page. Open Index.cshtml.cs and change the class to the code shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

using System;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc;

using Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.RazorPages;

namespace ClientWebApp.Pages

{

public class IndexModel : PageModel

{

private bool PersistentLoginAttempted = false;

private const string PersistentLoginFlag = "persistent_login_attempt";

public IActionResult OnGet()

{

// Always clean up an existing flag.

bool FlagFound = false;

if(!String.IsNullOrEmpty(TempData[PersistentLoginFlag] as string))

{

FlagFound = true;

TempData.Remove(PersistentLoginFlag);

}

// Try to refresh a persistent login the first time an anonymous user hits the index page in this session

if(!User.Identity.IsAuthenticated && !PersistentLoginAttempted)

{

PersistentLoginAttempted = true;

// If there was a flag, this is the return-trip from a failed persistent login attempt.

if(!FlagFound)

{

// No flag was found. Create it, then begin the OIDC challenge flow.

TempData[PersistentLoginFlag] = PersistentLoginFlag;

return Challenge("persistent");

}

}

return Page();

}

}

}

The real work is performed by the return Challenge("persistent") statement. That emits the IActionResult equivalent to calling HttpContext.ChallengeAsync, which instructs ASP.NET Core to begin the authorization flow named persistent. However, if we only triggered that flow, the client app would get locked into a redirect loop with Identity Server: the user would request the landing page which starts the flow, Identity Server would send back some kind of response, the client app would start processing the Index page’s OnGet again which would start a new login flow back to Identity Server, and the whole process would loop until Identity Server’s rate-limiting feature refused the connection.

The page needs a way to remember across sessions whether or not it is in the middle of this flow. We achieve this by dropping a flag into TempData, the cookie-based session-data feature of Razor Pages. We also use the PersistentLoginAttempted boolean to track whether we’ve already attempted to refresh the persistent login within the current session, since that should only be done once per session.

Identity Server Configuration

There is one final piece to the puzzle: the client configuration in the Identity Server project. If you run the client at this stage, Identity Server will respond with an unauthorized_client error because Identity Server doesn’t recognize the login-redirection endpoint specified by our new scheme (/signin-persistent). This is a security feature preventing an attacker from tricking a user into logging in, then redirecting them to a malicious site which could operate under their newly-authenticated identity.

Open the ConfigIdentityServer class in the Identity Server project. Around the middle of the GetClients method you’ll see a statement that assigns a value to RedirectUris. Notice that value is actually an array. Add the new scheme’s URI to the list.

1

2

3

4

5

// replace with this

RedirectUris = {

"https://localhost:5002/signin-oidc", // after normal login

"https://localhost:5002/signin-persistent" // try persistent login on new session

},

Now Identity Server will recognize both schemes as valid redirect targets for the client id mv10blog.client.

Test Run

Start Identity Server, then start the client. Click Login, sign in with Google, and upon your return to the client app, you will see the welcome message and the Account and Logout links. Close the browser, then restart the client app, and after a few seconds you will return to the landing page with your credentials restored.

It is also easy to demonstrate that an expired login results in transparent anonymous access upon the user’s next visit. Click Logout, then stop both applications.

You may remember from the earlier IdentityServer4 article that we changed external login cookies to a long-duration expiration. This is the relevant part of code we changed in the IdentityServer Quickstart’s AccountController.ExternalLoginCallback method.

1

2

3

4

// make external logins persistent rather than session-duration

AuthenticationProperties props = new AuthenticationProperties();

props.IsPersistent = true;

props.ExpiresUtc = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow.Add(AccountOptions.RememberMeLoginDuration);

In the Identity Server project, open AccountOptions and change the duration to a very short period as shown.

1

2

// temporary change for demo purposes

public static TimeSpan RememberMeLoginDuration = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(1); // TimeSpan.FromDays(30);

Now restart both projects, log into your account, and close down the client while you are still logged in. Wait at least 1 minute. The login cookie will now be recognized as expired the next time it is checked. Restart the client – you will be treated as an anonymous user again. In effect, you were logged out due to expiration.

(Don’t forget to undo the 1-minute timeout!)

Conclusion

This article demonstates how easy it is to achieve true first-class persistent login with Identity Server 4 and ASP.NET Core. At this point in my impromptu Identity Server and ASP.NET Core series, you should have all the tools you need to build and deploy a secure real-world application with both local-account and third-party authorization support.

Comments