.NET Core Class Library Dependency Injection

Adding dependency injection to class libraries in .NET Core 2.0 is almost as easy as DI in ASP.NET, but class libraries may require a few extra tricks that aren’t immediately obvious.

Any MVC developer is familiar with the stack of services.Add commands in Startup, and many will have encountered AddTransient, AddScoped, and possibly AddSingleton for registering new service interfaces for injection. Most blog articles online never go beyond the Startup and controller scenario, and it can be difficult to find good, correct advice about how to extend DI into an external class library.

If you’re reading this, it’s likely you already understand DI. The primary benefit touted for DI is unit test mocking, but in my opinion the real value is consistency. The older approach of static classes and methods for libraries definitely prevents mocking, but it also denies the opportunity to leverage other DI features like scoped and lazy instantation.

NuGet Package for DI

The good news is Microsoft externalized their DI solution when they began working on ASP.NET Core. Now it lives in the NuGet package Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection. Pull that package into your class library and you’re nearly finished!

This package gives you access to several important tools. We’ll focus on three of them.

Extending IServiceCollection

This is the familiar services collection used in ASP.NET Core’s Startup class. It stores all of the available services and various configuration details for each registered service. In DI terminology, that Startup process is known as the composition root. In practical terms, it’s the place where injectable services are registered.

You don’t need ASP.NET to use DI and the services collection. A simple console program could act as the composition root by creating an instance of this collection and using it to register services.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

public class Program

{

public static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var services = new ServiceCollection();

services.AddUsefulService();

}

}

Your class library should make it easy for the consuming application to register its services. In ASP.NET the many services.Add options (like AddUsefulService above) are implemented as extensions of IServiceCollection, and your class library can do exactly the same thing.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

namespace Example.Library.Azure

{

public static class IServiceCollectionExtension

{

public static IServiceCollection AddExampleAzureLibrary(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddScoped<IGetSecret, GetSecret>();

services.AddScoped<IKeyVaultCache, KeyVaultCache>();

services.AddScoped<IBlobStorageToken, BlobStorageToken>();

services.AddScoped<IBlobWriter, BlobWriter>();

return services;

}

}

}

Once this is built and your client application has a reference to the library, it can register the library’s services with a single line of code. This is how the example abouve would be used in an ASP.NET Core Startup class.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

using Example.Library.Azure;

namespace Website

{

public class Startup

{

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddExampleAzureLibrary();

}

}

}

I usually take the approach of adding an extension for each namespace in the library, and then one big extension that pulls together all the namespace-level registrations. If your library is particularly complex, you may want to take a different approach, creating several extensions that register various logical commonly-used combinations of your namespaces. It’s a decision to be made on a case-by-case basis.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

using Example.Library.Azure;

using Example.Library.Database;

using Example.Library.Security;

namespace Example.Library.Utilities

{

public static class IServiceCollectionExtension

{

public static IServiceCollection AddExampleLibrary(this IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddExampleAzureLibrary();

services.AddExampleDatabaseLibrary();

services.AddExampleSecurityLibrary();

return services;

}

}

}

I’m writing the end of this section almost four years later – a reader pointed out that I don’t actually cover the usage of any of the examples shown above. I originally wrote this under the assumption that readers were already familiar with DI as it was used in ASP.NET Core, but it’s easy enough to round out this section with another example. Microsoft’s DI uses constructor-based injection (there are other DI techniques out there with various pros and cons). The earlier code snippet for AddExampleAzureLibrary registers four services:

IGetSecretIKeyVaultCacheIBlobStorageTokenIBlobWriter

Those examples were based on an earlier article I had written about storing data in Azure Key Vaults. Let’s say you are creating a class that retrieves that data by calling a Fetch method on an IGetSecret object (ignoring that a real Azure library would use async Tasks). Elsewhere during program initialization, you would have already called services.AddExampleAzureLibrary() which tells DI how to associate those interfaces with their concrete implementation classes. To use it, you need only declare IGetSecret in the class constructor, and DI does the rest:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

using Example.Library.Azure;

namespace MySecretsProgram

{

public class SecretsReader

{

// the constructor will set this

private IGetSecret getSecret;

// DI populates the getSecret argument

public SecretsReader(IGetSecret getSecret)

{

// store the reference for later use

this.getSecret = getSecret;

}

public string Read(string key)

{

// use the private reference

return getSecret.Fetch(key);

}

}

}

(Side note: when I wrote the article in 2018, I tended to prefix the constructor arguments with di, but the technique shown above – using the same name for the argument and the private reference, and differentiating with the this keyword – has become popular over the years and it is my preference.)

Now, in order for DI to populate the constructor argument, that means DI must instantiate the class you just created. Ideally, this means SecretsReader would also be registered as a service, and any other class which needs that object would also use injection to obtain a reference. Similar to async/await, the use of DI tends to have a ripple effect – it is usually easiest to use DI everywhere, top to bottom (which is part of the reason I wrote this article, it’s nice if “top to bottom” includes your stand-alone libraries). But arguably, there are exceptions, which is a nice segue to the next section of the original article…

(My thanks to Gary D. for suggesting the additional clarification.)

Embrace the Anti-Pattern

The other two tools we’ll discuss from the DI NuGet Package are:

ActivatorUtilitiesIServiceProvider

These allow us to retrieve registered services without declaring dependencies in the constructor.

At this point, the Pattern Priesthood will begin freaking out, reciting mystical lore: “Requesting services without dependency injection is the Service Locator anti-pattern!” This is often a valid concern, but we’ll take a look at a couple of equally-valid exceptions to this advice. (And advice is all architectural patterns are. All too often Architecture Astronauts invoke the Secret Truths of Patterns, to be treated by their flock as inviolable rules handed down by Authorities. Hopefully one of these Authorities has declared that to be an anti-pattern!)

All joking aside, I will emphasize that I do agree DI is usually preferable to Service Locator (otherwise there would be little point to writing this article), but class libraries are a special case where “doing the wrong thing for the right reasons” sometimes applies.

.NET Core DI uses the common approach of declaring dependencies in the constructor. The parameters define the dependencies as interface references, and the DI system wires up the parameters with concrete instance references.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class MyUtility

{

private readonly IUsefulService svc; // local reference so we can use the service

public MyUtility(IUsefulService diSvc) // dependency delcared in constructor

{

svc = diSvc; // save the reference provided by DI

}

// other methods

}

The Service Locator anti-pattern is when a method inside the class uses some other technique to acquire a reference to an object managed by the DI system. The dependency is not declared in the constructor and the reference is not established when the class is created.

This article was inspired by my efforts to convert an old-style static class library to DI. There was existing code in both the library itself and dependent applications with certain patterns of usage relating to the static design that would have been very time-consuming and expensive to refactor into a 100% pure DI architecture.

Let’s examine two cases where the Service Locator anti-pattern was more useful than harmful.

Minimizing Complexity

The first case where it’s reasonable to apply Service Locator is when the alternative adds significant complexity. Every developer has run into circular references. They almost always indicate there is a problem with the overall design, but on rare occasions they make sense. This is a prime example of “doing the wrong thing for the right reasons” you may encounter while developing class libraries. (If you want examples from a Higher Authority than me, check out the circular references within the .NET Framework; Microsoft even uses multi-pass compilation with custom tooling to build these DLLs.)

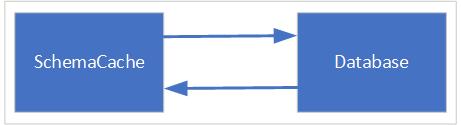

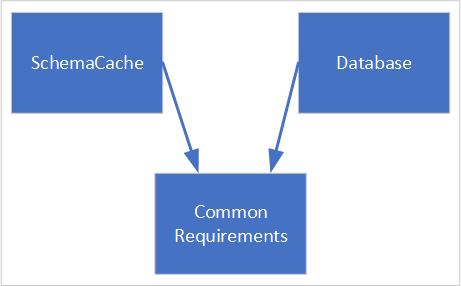

The static library I was converting to DI had just such a scenario. The classes were very simple. The separation of concerns was very clean: one encapsulated routine, low-level database access, and the other cached database schema and performed related operations. Some client apps and parts of the library itself would reference the database class first, and others would reference the schema first. If the schema cache wasn’t initialized, the schema class would use the database class to open a connection. The very same database method that opened connections checked that the schema was initialized since many other database methods used the schema for things like parameter typing. It was a classic circular reference scenario.

The standard recommendation for resolving circular dependencies is to analyze both classes and break out the dependencies into a third class. Each of the original classes can then depend on the new third class. However, this just felt wrong. As I described above, both classes felt well-designed and appropriately-sized. Breaking them up purely to make DI happy would also require significant changes throughout the rest of the code base. The standard answer just felt wrong.

IServiceProvider

It turns out there was exactly one call to the database class from the schema class. It was far cleaner to simply embrace the Service Locator anti-pattern and grab a reference to the database class on the rare occasion it was needed. The DI package includes a ServiceProvider class which does exactly that: provides references to services registered for DI.

Before the change, the static classes looked something like this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

public static class SchemaCache

{

private static List<TableDefinition> Table { get; }

private static List<ColumnDefinition> Column { get; }

public static bool IsInitialized { get => (Table == null); }

public static async Task Initialize(SqlConnection conn = null;)

{

var connection = (conn != null) ? conn : await Database.GetOpenConnection();

// ... load the schema

}

public static async Task SomeOtherMethod()

{

if(!IsInitialized) await Initialize();

// ...

}

}

public static class Database

{

public static async Task<SqlConnection> GetOpenConnection()

{

var connection = new SqlConnection(connectionstring);

await connection.OpenAsync();

if(!SchemaCache.IsInitialized) SchemaCache.Initialize(connection);

return connection;

}

}

The naive circular reference version is shown below. This throws a circular dependency exception at runtime the first time either class is referenced.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

public class SchemaCache

{

private readonly IDatabase db;

public SchemaCache(IDatabase diDb)

{

db = diDb;

}

public async Task Initialize(SqlConnection conn = null;)

{

var connection = (conn != null) ? conn : await db.GetOpenConnection();

// ... load the schema

}

// other properties and methods omitted

}

public class Database

{

private readonly ISchemaCache schema;

public Database(ISchemaCache diSchema)

{

schema = diSchema;

}

public async Task<SqlConnection> GetOpenConnection()

{

var connection = new SqlConnection(connectionstring);

await connection.OpenAsync();

if(!schema.IsInitialized) schema.Initialize(connection);

return connection;

}

}

We eliminate the circular reference by removing the IDatabase dependency in the SchemaCache constructor, replacing it with a dependency on IServiceProvider instead. The Database class is unchanged from the version shown above – it remains dependent upon an injected reference to SchemaCache.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public class SchemaCache

{

private readonly IServiceProvider provider;

public SchemaCache(IServiceProvider diProvider)

{

provider = diProvider;

}

public async Task Initialize(SqlConnection conn = null;)

{

var db = diProvider.GetService<IDatabase>();

var connection = (conn != null) ? conn : await db.GetOpenConnection();

// ... load the schema

}

// other properties and methods omitted

}

Creating Objects with Dependencies

The second case where I felt the Service Locator anti-pattern was appropriate is very easy to define. Part of the library needed to create multiple instances of a class which itself declared a dependency. (Remember, this used to be a static library: the class used to simply call the static methods it needed from the dependency.) It is very definitely not a good idea to call new on a class with dependencies – it defeats the whole point of doing DI at all: the creating class becomes much more tightly-tied to the target class, the creating class may need to declare dependencies it doesn’t otherwise need purely so it can create the target class, and so on.

The library created a List of data items, and those objects depended on another class for data-sanitization. The original static version had the following structure (greatly simplifed here, obviously).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

public static class Sanitizer

{

public static string SanitizeInput(string input) { ... }

}

public class DataItem()

{

public string Data { get; set; }

public string ProcessData()

{

return Sanitizer.SanitizeInput(Data);

}

}

public class DataManager()

{

public List<DataItem> ReadData(List<string> rawData)

{

var list = new List<DataItem>;

foreach(string data in rawData)

{

var item = new DataItem();

item.Data = data;

}

return list;

}

}

The DI version of this would register ISanitizer as a DI-ready service, and DataItem would add a constructor requesting an instance of an ISanitizer object. But how does DataManager iterate over the raw input data, creating new DataItem instances as it goes? Each new DataItem has dependencies that need to be resolved.

ActivatorUtilities

The solution is the CreateInstance method in the ActivatorUtilities class from the DI package. As the name suggests, it will create a new instance of the requested type, processing any DI requirements in the process. The method requires an instance of IServiceProvider so the class in question has to declare a dependency on that.

The DI-friendly version of the three classes are as follows.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

public class Sanitizer

{

public string SanitizeInput(string input) { ... }

}

public class DataItem()

{

private readonly ISanitizer sanitizer;

public DataItem(ISanitizer diSanitizer)

{

sanitizer = diSanitizer;

}

public string Data { get; set; }

public string ProcessData()

{

return sanitizer.SanitizeInput(Data);

}

}

public class DataManager()

{

private readonly IServiceProvider provider;

public DataManager(IServiceProvider diProvider)

{

provider = diProvider;

}

public List<DataItem> ReadData(List<string> rawData)

{

var list = new List<DataItem>;

foreach(string data in rawData)

{

var item = ActivatorUtilities.CreateInstance<DataItem>(provider, null);

item.Data = data;

}

return list;

}

}

Conclusion

As you can see, it’s very easy to provide first-class support for dependency injection in .NET Core class libraries. The library itself can leverage dependency injection internally, as well as being available service-style to other libraries or applications that consume the library.

Comments