Reusable Dependency Injection for Azure Function Apps

We show how to turn an Azure Function dependency injection experiment into a reusable library for any Azure Function V1 project.

Important: When I originally wrote this, I didn’t realize that Azure Function names defined by the [FunctionName] attribute are meant to be global at the csproj level. That means you should only have one trigger with the default RegisterServices name. That actually ends up working well in practice. Since a Functions project should be small and tightly-focused, typically the individual function methods tend to need most or all of the same services anyway. (Shortly after I posted this, Functions 1.0.8 was released and the build will fail on duplicate Function names; I half suspect this article was the reason, one of the pull-request contributors forked this project.)

Functions V2: The approach in this article only supports .NET Framework-based Azure Functions V1 apps. Microsoft is working on dependency injection support for .NET Core V2 apps, but you can find my interim solution in this newer article.

Code for this article can be found here.

Dependency injection has become a standard technique for writing testable, loosely-coupled applications and libraries. And yet, Azure Function users have been waiting for almost two years for DI support. The original request was posted in 2016, and it wasn’t until a few days ago that Microsoft linked it to an open GitHub issue that has been active since 2017.

I have a project with a large, complex DI-driven library which must be shared between several web apps as well as a variety of services implemented as Azure Function apps. I knew DI wasn’t “officially” available and would be a challenge. I struck paydirt when I found the GitHub discussion about DI. Two users contributed their interesting experiments in Function DI support. Last October, basic DI was accomplished by BorisWilhelms, but that implementation tightly ties service registration to the rest of the injection system. Just a few days ago, user yuka1984 forked that project to add an inspired custom Function trigger that moves DI service registration out of the injection system and into the Function app.

I spent some time reviewing their work and realized they were very close to a reusable library. I’ve done quite a bit of cleanup, commenting, and refactoring of their code, and I made quite a few changes to the code that demonstrates how the different use-cases work, but the basic concept is unchanged and they deserve all the credit for their insights.

Using the Attributes

Azure Functions are static classes, which makes them incompatible with the normal constructor-based DI. BorisWilhelms’ solution was to create an [Inject] attribute which can be applied to Function parameters to declare dependencies. From there, yuka1984 created an injection-configuration custom Function trigger and changed the [Inject] attribute to also reference the function name that registers the DI services. I renamed the trigger to [RegisterServicesTrigger] to better reflect what happens when the Functions execute.

Injection configuration is triggered by the injection request.

The result is very easy to use.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

public static class DemoFunction

{

[FunctionName("QueryUsefulData")]

public static async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Run(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get")] HttpRequestMessage req,

[Inject("Registration")] IUsefulDataProvider data)

{

return req.CreateResponse(data.GetUsefulData());

}

[FunctionName("Registration")]

public static void Config([RegisterServicesTrigger] IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddSingleton<IUsefulDataProvider, UsefulDataProvider>();

}

}

Although it isn’t obvious from looking at the code above, one of the really interesting ideas in yuka1984’s solution is to use a Lazy<> approach to activation of the trigger Function. Thus, service registration is not actually processed until it is used, and it is only processed once regardless of how many [Inject] tags reference it.

Since Azure Function apps are only C# class libraries as far as the compiler is concerned, treating the end-result as a library was trivial. I just created a new Function project to act as the “main” project (the one that actually runs Functions) and referenced the DI project from there. After a recompile, the attributes just work.

A useful feature I added is a default registration Function name of RegisterServices for the [Inject] attribute. Most Function apps will only need a single registration Function, and you’ll still have to add the [FunctionName("RegisterServices")] attribute to the trigger Function for it to work, but the trigger name should help to jog your memory.

Verifying Full-Graph Injection

Since my real-world use-case is a large, complex, DI-dependent utility library, I modified their demo code to demonstrate to my own satisfaction that dependencies declared by the injected objects would also be correctly resolved. I also made changes I felt better demonstrated the different service lifetimes.

The original demos used an IGreeter interface and classes to demonstrate injection. I moved these to a separate .NET Standard library project. In yuka1984’s version of the demo, he thoughtfully added a counter one of the IGreeter implementations to demonstrate that the AddSingleton registration was really exhibiting singleton behavior. My modification was to simply add ICounter which is injected into the concrete CountUpGreeter class.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public class Counter : ICounter

{

public int count { get; set; } = 0;

}

public class CountUpGreeter : AGreeter, IGreeter

{

private readonly ICounter counter;

public CountUpGreeter(ICounter counter) : base()

=> this.counter = counter;

public new string Greet()

=> $"Hello World, counter {counter.count++}, ms:{constructed.Milliseconds}";

}

A quick test shows the counter works, confirming that DI carries through to referenced members of the separate class library.

Demonstrating Singleton Services

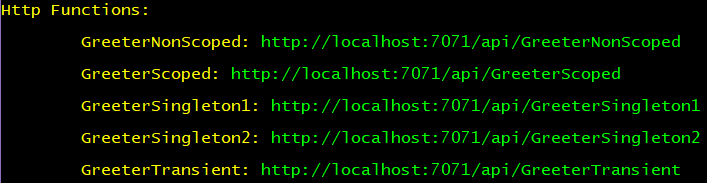

When you run the demo locally using the Azure Functions CLI, the console window dumps the URLs for any HTTP-triggered Functions defined in the application. Executing those functions is as easy as pointing your browser at them.

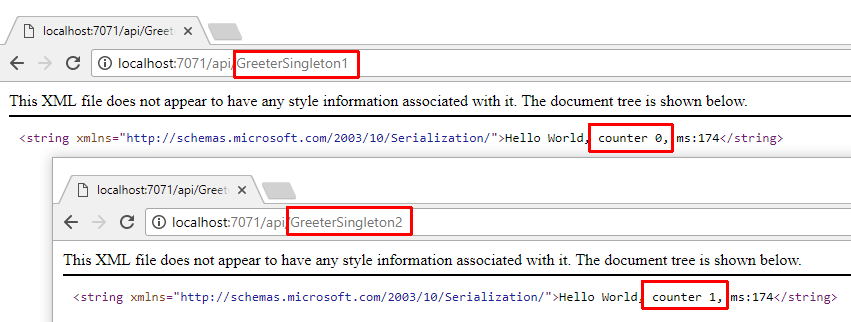

You can see there are two singleton URLs. Calling each of these proves they do indeed reference a singleton instance of the service thanks to yuka1984’s addition of an incrementing counter.

Demonstrating Transient Services

I was surprised that neither version of the DI experiments demonstrated transient registration. Transient services are even defined by the documentation as great choices for the kind of services Function apps are meant to provide.

Transient lifetime services are created each time they’re requested. This lifetime works best for lightweight, stateless services.

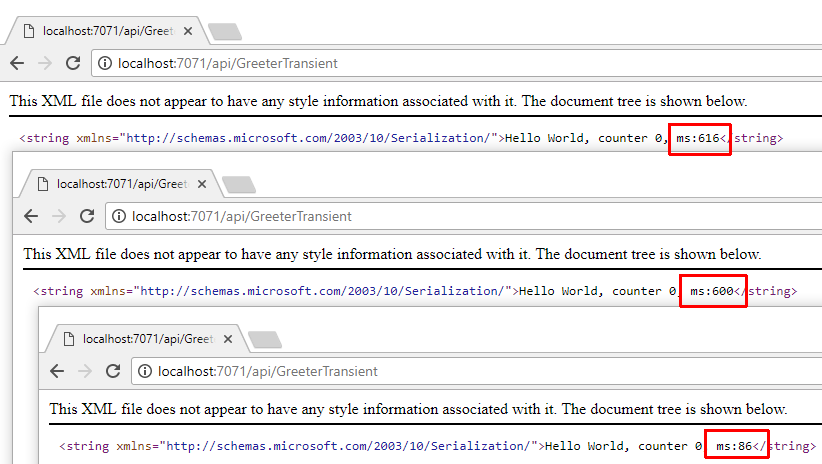

I added a constructed property to the AGreeter base class. It is set to the date and time when the constructor is executed, and is emitted at the end of the “greeting” string as ms:xxx. You can see that multiple injections of IGreeter registered with AddTransient show a different creation time on every call.

Demonstrating Scoped Services

The documentation says this about registering with AddScoped:

Scoped lifetime services are created once per request.

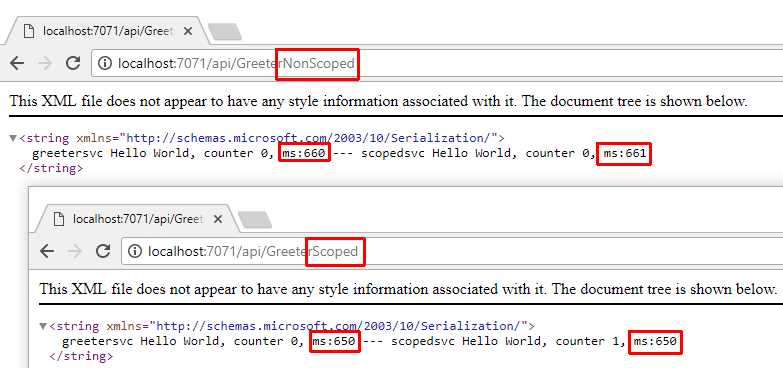

Unfortunately yuka1984’s scoped demonstration didn’t illustrate the effects of a scoped lifetime. It did register IGreeter using AddScoped but that alone won’t prove that the service is created once per request. To do this, some other service would have to be registered which also injected IGreeter during the same request. When IGreeter is registered as scoped, both injected services will show the same constructed millisecond timestamp from their references to IGreeter, but should IGreeter be registered as transient, each service will receive a new copy of IGreeter and exhibit different timestamps.

To show this, I created scoped and non-scoped variants along with an IGreeterConsumer service (which is always registered as transient; its lifecycle isn’t relevant, only the lifecycle of the IGreeter upon which it depends). You may have to run the non-scoped version a few times before you get different timestamps, it’s possible for both instances to be created within the same millisecond.

Service Registration Helpers

These demonstrations are simple, but a real-world class library is likely to have extensive and complex dependencies. It isn’t realistic to expect library-consumers to understand and register them correctly. Anyone who uses ASP.NET MVC or Core will recognize the many services.Add commands, which is an example of the solution to this problem. I added the same type of registration extensions that service-consumers can rely upon to ensure all the necessary interfaces are registered for injection.

For the Function DI demonstration project, the GreeterInjectionExtensions class provides three methods to register IGreeter as singleton, transient, or scoped lifetimes. The IGreeterConsumer registration extension only supports transient registration since that’s all the demo requires.

For my real-world class library, I have to consider many different use-cases. Web applications have broad coverage and a relatively long lifecycle, and so it is appropriate to provide a heavyweight, one-time-startup registration which literally registers the entire library. However, Azure Function apps have very different needs, so it was expedient to create additional extension methods specific to each utility service or even individual Functions, pulling in only the library interfaces required by those scenarios.

The Right Place to Register Services

Update: See the Update at the start of the article. In short, you probably should have just one services-registration trigger per csproj and this is handled/enforced by the Functions SDK if you rely upon the default RegisterServices trigger name. (You could still create multiple registration points by explicitly providing your own non-default names.)

Earlier I mentioned that I didn’t like the way service registration was tightly tied to the rest of the DI code in the original example from BorisWilhelms. When I first reviewed yuka1984’s changes, I also initially questioned service registration localized to the Function class.

I spent a few hours considering ways to move registration to a separate class within the Function app, similar to the way ASP.NET Core relies upon Startup.cs to register services. However, executing a Function in another class turns out to be very complicated (and maybe impossible) in a Function app. The class RegisterServicesTrigger has a method called AddConfigExecutor which defines the Lazy<> reference to the configuration Function. In the source, you’ll find the following line of code:

1

2

3

executor.TryExecuteAsync(

new TriggeredFunctionData() {TriggerValue = services},

CancellationToken.None).GetAwaiter().GetResult();

That causes the WebJob library to execute a Function. TriggeredFunctionData optionally allows for a custom invoker to execute the target, but an invoker is fairly complex (take a look at the code for the default invoker), and more importantly, right now Microsoft has the IFunctionInvoker interface declared as internal, so I couldn’t roll my own even if I really wanted to tackle that headache.

Fortunately, after thinking about it for awhile, I’ve concluded that service registration within each Function class is a good fit for the Function application model.

As mentioned in the previous section, when a web application uses my utility library, there is a good chance most of the library will be used at some point. It is reasonable to just register everything in one shot. The web application runtime model is relatively loose about memory usage and in comparison to the default five-minute maximum Function lifecycle, a web application can remain active in memory for many hours.

On the other hand, Functions are meant to be very self-contained and very memory- and processing-efficient. These concerns should be reflected in the dependencies the Functions require and how related services are registered. Therefore, it makes sense to me that service registration should also be localized to the Function’s class. Yes, it is still important for the library to provide helpers so that the Function isn’t too tightly tied to internal library requirements, but registrations should be kept as streamlined as possible.

Multiple Composition Roots

There is one unusual side-effect of registering services via Function trigger: the application effectively has multiple composition roots. Normally, an application registers services once at startup. But the nano-service orientation of a Function application means that each invocation of the application potentially has different, very tightly-constrained requirements. As a result, a Function app which provides several logically-related services may have very different runtime requirements.

The implementation of service registration as separate Lazy<> instances means each registration Function acts as a completely unique composition root. In fact, an individual Function can even reference multiple registration trigger Functions (ie. more than one composition root), even providing references to the same interface but registered with different lifetimes from other injected references on the same Function. It’s hard to imagine a use for this last bit, but the flexibility is certainly interesting.

// TODO: WebJobs Host JobActivator

There are quite a few examples online of implementing DI for WebJobs. The WebJobs host configuration has a property called JobActivator that will perform DI when pointed to a container, which in .NET Core DI is an IServiceProvider. I noticed RegisterServicesTrigger implements the WebJobs IExtensionConfigProvider interface, which requires just one method:

1

public void Initialize(ExtensionConfigContext context)

The ExtensionConfigContext object’s Config property returns a reference to the JobHostConfiguration, which suggests a more direct route to Function DI may be available to us.

I suspect it would work to register a class-level IFunctionInvocationFilter and point the activator to the DI provider, creating a composition root for that Function class. (Filters can also be registered at other levels such as globals or individual Functions, so other DI composition techniques should be possible, but as I explained earlier, class-level composition “feels” right.)

I hope to find some time to investigate this later.

Update: I did look into this for another project, and unfortunately, as far as I can tell, the underlying JobHostConfiguration is inaccessible once the Functions layer is up and running.

Update: NuGet Packages

Feb-02-2018 Update: When I build libraries I share them to my other apps as local NuGet packages to avoid transient dependency problems. For some reason, a project that depends on the Azure Functions SDK for version 1 (.NET Framework) prevents Visual Studio’s automatic package generation from working.

The solution is simple – remove the reference to Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions and create references to the individual packages. You’ll want to take a look at the package dependencies in your Azure Functions application that will use DI. Version 1.0.7 of the SDK is still stuck on the beta versions shown below, and unfortunately the dependency is version-specific (= rather than >=) which means you can’t reference the release versions yet, even though they’ve been available for a while (a lot of this Azure stuff has become a modern-day package-based version of DLL Hell).

| Package | Version |

|---|---|

Microsoft.Azure.Webjobs |

v2.1.0-beta4 |

Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions |

v2.1.0-beta4 |

Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Extensions.Http |

v1.0.0-beta4 |

I’ve updated the GitHub project accordingly.

Conclusion

Thanks to the efforts of BorisWilhelms and yuka1984, we have an easy-to-use, highly flexible, reusable dependency injection library for Azure Function apps. They may have handed Azure Function DI to Microsoft on a platter, although the possibility of a JobActivator-based solution is intriguing. Hopefully my contributions will prove helpful, and here’s hoping we see some type of official DI support soon!

Comments