Cache and Release Resources in Azure Functions

Azure Functions don’t have a clearly-defined lifecycle, so it appears difficult to safely cache and release objects that are expensive to create but require Dispose or Close calls. This is a short article demonstrating a technique for safe caching of a single reference as well as a threadsafe pool of references for Function apps (v1 and v2).

Many Azure “Best Practices” guides recommend caching heavyweight object references. Some examples like this resort to static references, but none of them that I could find demonstrate actually releasing those resources. Another example of a recommendation to rely on caching is the Cosmos DB DocumentClient API documentation, which states:

It is recommended to cache and reuse this instance within your application rather than creating a new instance for every operation.

There’s no example of this (and it probably wouldn’t apply to Function apps anyway). The documentation moves on to discuss proper disposal through using and try/finally blocks, neither of which are useful in a cache-and-reuse scenario.

Azure Functions are challenging in this respect because their static nature is meant to enforce a stateless design. Presumably we are expected to pretend there is no underlying application lifecycle. Unfortunately, the real world is not so neatly arranged.

The safe-release technique is simple enough to describe in one sentence: Hook the ProcessExit event.

The code in this article is based upon a real library I’m working with, so the examples use constructor-based dependency injection and interfaces for DI service registration. You can read more about a DI technique for Azure Functions in an earlier article I wrote recently, Reusable Dependency Injection for Azure Function Apps.

Caching a Single Instance

Some resources only require caching a single instance. HttpClient is an example of this. The implementation only requires a few lines of code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public class HttpClientCache : IHttpClientCache

{

private static readonly HttpClient client = new HttpClient();

public HttpClientCache()

=> AppDomain.CurrentDomain.ProcessExit += (s, e) => client.Dispose();

public HttpClient Client { get => client; }

}

Consumers declare a dependency on IHttpClientCache then just use the Client reference directly.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public class FetchAndParse

{

private static readonly IHttpClientCache http;

private readonly IDocParser parser;

public FetchAndParse(IHttpClientCache iHttp, IDocParser iParser)

{

http = iHttp;

parser = iParser;

}

public async Task<ParsedDoc> Fetch(string uri)

{

using(Stream stream = await http.Client.GetStreamAsync(uri))

{

var results = await parser.ParseStream(stream);

return results;

}

}

}

Of course, it works the same way from within an Azure Function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

[FunctionName("FetchParseQueueListener")]

public static async Task Run(

[ServiceBusTrigger("fetch-and-parse", AccessRights.Listen)]FetchParse message,

[Inject] IHttpClientCache http,

[Inject] IDocParser parser)

{

using(Stream stream = await http.Client.GetStreamAsync(message.uri))

{

var results = await parser.ParseStream(stream);

// omitted: post message

}

}

// omitted: DI service registration

Caching Multiple Instances

Some heavyweight resources are not globally reusable. An example of this is the Azure Service Bus MessageSender object, each of which is tied to a specific queue or topic after creation. Our application uses many queues, and some Functions can send hundreds or even thousand messages in response to a single initial event, so we definitely don’t want to allocate and tear-down these expensive objects over and over again.

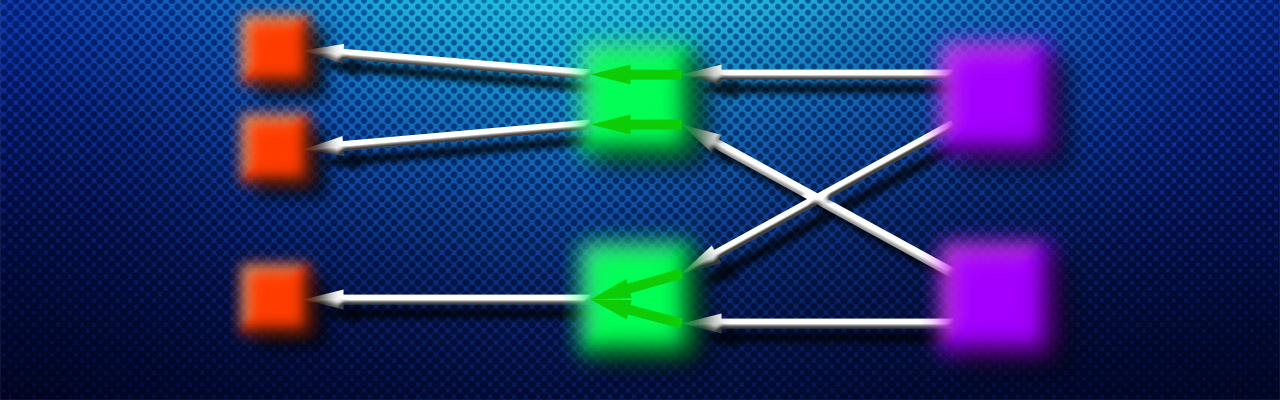

In this example, we combine the ProcessExit approach with a technique I first read about in Andrew Locke’s article last year. This is a thread-safe approach to on-demand instantiation with Lazy<> factories stored in a ConcurrentDictionary. The use of Lazy<> ensures one and only one instance with the desired configuration (in this case, the queue name) will be created regardless of whether multiple clients make overlapping requests for the resource.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

public class MessageSenderCache : IMessageSenderCache

{

private readonly string connect;

public MessageSenderCache(IConfigCache config)

{

connect = config.QueueSenderConnectionString;

AppDomain.CurrentDomain.ProcessExit += CloseMessageSenders;

}

private ConcurrentDictionary<string, Lazy<IMessageSender>> cache

= new ConcurrentDictionary<string,

Lazy<IMessageSender>>(StringComparer.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

public async Task<IMessageSender> GetMessageSender(string queueName)

{

return cache.GetOrAdd(queueName,

new Lazy<IMessageSender>(() =>

{

return new MessageSender(connect, queueName);

})).Value;

}

private void CloseMessageSenders(object sender, EventArgs e)

{

foreach(var n in cache)

{

Lazy<IMessageSender> wrapper = n.Value as Lazy<IMessageSender>;

IMessageSender send = wrapper.Value as IMessageSender;

send.CloseAsync().GetAwaiter();

}

}

}

Usage in a Function is equally simple.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

[FunctionName("FetchParseQueueListener")]

public static async Task Run(

[ServiceBusTrigger("fetch-and-parse", AccessRights.Listen)]FetchParse message,

[Inject] IMessageSenderCache sendercache,

[Inject] IHttpClientCache http

[Inject] IDocParser parser)

{

var sender = await sendercache.GetMessageSender("parsed-results");

using(Stream stream = await http.Client.GetStreamAsync(message.uri))

{

var results = await parser.ParseStream(stream);

var payload = Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(JsonConvert.SerializeObject(response));

var message = new Message(payload)

{

ContentType = "application/json"

};

await sender.SendAsync(message);

}

}

// omitted: DI service registration

Register with AddSingleton

These examples would be easy to convert to a static library approach, which is probably how I’d implement them if we were not using the dependency injection extensions in our Functions apps, and if we didn’t have non-Functions dependencies on the libraries.

If your cachces are injected services, it is important that the services be registered with AddSingleton, otherwise you’ll incur the very startup overhead you’re trying to avoid, and the application will rarely (if ever) correctly release those references.

Keep your cache services as lightweight as possible, since any dependencies they declare will also have to be singletons. (This constraint avoids a problem known as captive dependency.)

Failure Scenarios

By sheer coincidence, last month I helped a colleague resolve memory exhaustion shutdowns related to leaking Entity Framework resources. He was attempting to correct the problem using class finalizers. I referred him to a very good article by Rayomond Chen explaining why finalizers aren’t reliable: Everybody thinks about garbage collection the wrong way. If you’re not familiar with the issue, finalizers seem like a great tool to solve this problem, but unfortunately they’re far too finicky to be of much use.

For the sake of completeness, I’ll also point out that ProcessExit itself is not guaranteed to be called. As far as I can tell, though, this is really only a problem in what Mike Stall referred to as “rude process shutdown” (ie. killing the process). I don’t think it would be reasonable to expect an orderly shutdown in a kill scenario anyway, so I’m not terribly concerned about this edge-case.

I’ve done quite a bit of logging with both Functions and console-based test clients and I’m very satisfied with the reliability of this technique.

Compatible with Framework and Core

This technique works for both Azure v1 Functions based on .NET Framework and v2 based on .NET Core. The AppDomain APIs were not originally part of .NET Core but Microsoft brought them back as part of the major API expansion in .NET Standard 2.0.

https://apisof.net/catalog/System.AppDomain.ProcessExit

Possible Alternative

I like the ProcessExit approach presented here because my libraries are also used by ASP.NET Core web apps, not just Azure Functions.

I haven’t tried it yet, but in a pure Functions environment, it may be possible to register a global-scope WebJobs invocation filter, then Dispose or otherwise release references in the OnExecutedAsync method. The global scope is the “outermost” layer of filter registration, so it looks like that event implies the host is shutting down.

Conclusion

Safe and efficient caching and cleanup of heavyweight resources is easy once you’ve familiarized yourself with these techniques. Longer term I’m hoping Microsoft exposes at least minimal lifecycle events to Azure Function apps in some official capacity, but at least we have some alternatives in the interim.

Comments