How Web Apps Ruined Developer Productivity

Y2K heralded more than date-format hysteria, it was the dawn of web-based applications. I argue it was also the beginning of a steady and costly decline in enterprise developer productivity.

If you read my blog for technical content, you can probably skip this one. It’s an opinion piece about an enterprise development issue that has bothered me for many years.

Before I begin, I am certainly not arguing that the Internet or the web is somehow bad. I’m not even arguing that web-based apps are bad: anyone old enough to remember the pain of finding and buying plane tickets before the days of Expedia or Kayak will understand that. I used the Internet in the early 90s through a dial-up modem connection to a shell account provided by a FIDOnet BBS. I had a very expensive CompuServ dial-up account for Usenet access, and I spent years reading email with pine. I used the earliest Yahoo plain-text list of links from a genuine Mosaic browser. The Internet and I go way back.

No, my gripe is about the closed ecologies of enterprise development, which have been Doing It Wrong for almost 20 years. And things seem to be getting worse.

Rise of the Web Application

In the early days of the World Wide Web, the paradigm was “online library,” and even today, almost 30 years later, browsers are still highly document-oriented. At first, you picked your way through links to find other pages of interest, and more often than not, you had to just know the address where something useful could be found. Search was simple and not especially good. Modern all-seeing, relevance-ranking search engines were 15 years in the future.

A few years later, Netscape decided their variant of the Mosaic browser needed a scripting language. Sun was waging war with Microsoft and convinced Netscape that Java was their path to success. The new scripting language was released with the name JavaScript, even though it had little in common with the Java language, and within a year people were talking about “the browser wars.”

Dealing with incompatibility during the browser wars was painful and annoying, but arguably, it did drive innovation. Browser-makers raced to add new features and capabilities. Thanks to incremental scripting-language improvements and the implementation of advanced styling features towards the end of the 90s (including that other ad-hoc train-wreck, CSS), web pages saw a sharp increase in complexity and capability.

More importantly, the web had been successfully monetized: both Ebay and Amazon opened their marketplaces in 1995. Thanks to increasing availability of affordable high-speed Internet connections in the home and workplace, online shopping funded professional-grade development of large-scale websites, and the web-based application was born.

Over 20 years later, the line drawn between “web site” and “web app” is still fuzzy at best. Virtually all web pages use some script code, so that isn’t a useful definition. Some sites such as Wikipedia are vast and complex, but aren’t usually thought of as a web application. Others, such as Netflix, have very application-like capabilities and behaviors, and yet the average man on the street probably draws a distinction between a Netflix app and the Netflix web site. If I were to venture to define “web-based application,” it would probably be a site that allows a user to perform useful operations, often including creating and saving data, and is the sort of thing you wouldn’t be surprised to see implemented as a traditional, locally-installed desktop application.

There can be no doubt that the world loves web apps. Whatever definition you choose, the fact remains that Amazon, Ebay, Netflix and thousands of other successful businesses simply wouldn’t exist without something like web browsers making their services conveniently and instantaneously available. I certainly love them: thanks to almost-daily Amazon orders, I’m on a first-name basis with our UPS delivery man.

Slinging Code Like It’s 1999

In the late 90s while web apps were slowly building a head of steam, Microsoft arguably owned enterprise PC development at a level that was beyond the wildest dreams of any other company on the planet. This fact, not any desire to own the nascent browser market, was the real cause behind the war between Sun and Microsoft. Sun’s bread and butter was the corporate midsize-computer market in Unix shops, and they were being squeezed from both sides by clumsy mainframe modernization efforts and increasingly powerful PCs that were finally reaching server-level performance. For all practical purposes, those PCs universally ran Windows out of the box.

Enterprise PC developers during this time were most likely writing native Windows programs with Microsoft Visual C++ and Microsoft Visual Basic. There were many competing products such as Borland Turbo C and Powerbuilder, but none ever approached the popularity of Microsoft solutions. This isn’t to say there weren’t Unix shops out there, but Unix shops on budget-priced PC hardware just didn’t have the presence that Microsoft achieved.

In those days, servers generally had three main roles: file storage, database hosting, or external communications. If an enterprise had a web server, it was usually of the Company Intranet variety – largely static content, perhaps decorated with the company stock-ticker and friendly-looking pictures of senior management accompanied by inspiriational quotes. Client-server architectures were slowly being updated to multi-tier architectures and concepts like DCOM remoting were still relatively new concepts.

Today’s dev/ops processes just didn’t exist. Developers typically controlled the servers, we set up our own source control, we built installers, we figured out deployment strategies, and so on. End-users often called us directly with questions, ideas, and problems. The network guys that would eventually become “ops” were largely there to make sure the wires under the desk stayed connected to the switches and servers, that the backups ran, and that the firewalls kept bad guys from accessing management’s inspirational quotes posted to our intranet. Yes, there were other models – Unix shops had traditional sysadmins and different processes and security practices, and some Windows shops were more locked-down than others. The closer you got to mainframes, the more formalized things became. But by and large the “PC revolution” had happened so quickly, developers were the primary source of technology expertise, and it showed in our day-to-day activities.

We wrote stand-alone Windows applications, and managing completed applications was probably the biggest pain-point in enterprise software at the time. Challenges included deployment, installation, configuration, and upgrades. Products like Microsoft SMS were emerging to address these problems, but they were expensive, complicated, and new. The networking side of the house began taking over those responsibilities, but those products didn’t enjoy the rockstar popularity of “this new web thing” all the managers were reading about in PC Magazine.

And if I’m honest, speaking as a developer, it was new and therefore interesting. Many of us saw the potential of delivering business features without all that messy deployment and installation. In most cases developers still controlled the servers, so it also looked like an opportunity to side-step the managed-deployment bureaucracy that was slowly accumulating around products like SMS. Windows had a browser pre-installed, and with the flick of a configuration-switch, Windows servers became web servers. What could be easier than that? It was shiny and new, and it was an easy sell.

The enterprise web application was born.

Your New Dumb Terminal

The essential problem I have with enterprise web apps is that they’re a terrible waste of many kinds of resources. The first and most obvious resource they waste is desktop computing horsepower.

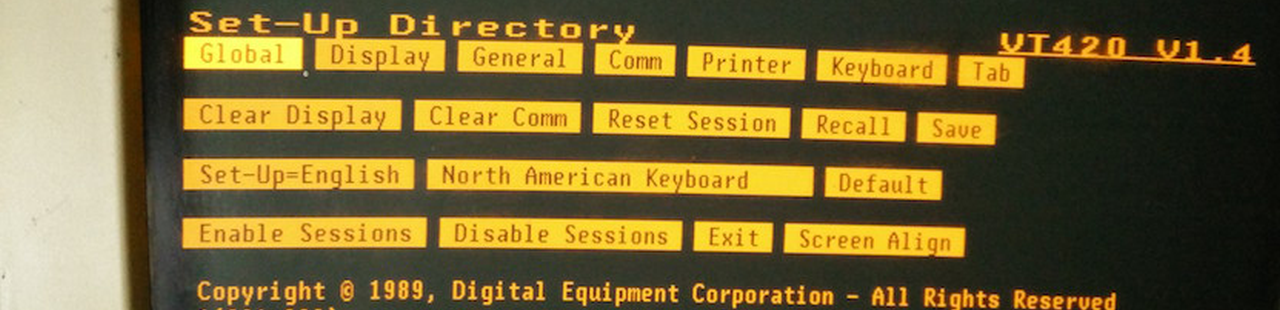

The world of mainframes gave us the dumb-terminal: a cheap keyboard and monitor that was literally a paperless version of the older typewriter-plus-printer for communicating with the “real” computer, the mainframe. Graphics were still weird, complicated, and expensive, so midsize minicomputers and eventually desktop microcomputing emulated this model.

But graphics were the future. Fierce competition didn’t allow PC manufacturers and software companies the luxury of the mainframe’s glacial progress. Faster, smaller, cheaper was the name of the game. Apple hijacked Xerox PARC’s GUI concept for their new Macintosh product, and Microsoft joined the fight with their competing Windows GUI. The term “operating system wars” entered the popular lexicon.

Fast-forward to the era of the web application, and the OS wars were largely resolved. Microsoft Windows owned the desktop, and Windows was making inroads in the newly-defined space of server-class PC hardware, which we now call “distributed” servers.

In a very real sense, the web-browser / web-server model is exactly where we started in the 60s and 70s when mainframe dumb-terminals were cutting-edge advances over punch cards and paper-based terminals. Presentation capabilities have improved considerably, and features like scripting and plugins provide capabilities far beyond the simple cursor-control and inverted-text display capabilities of mainframe dumb terminals. But at the end of the day, a browser is relatively useless without a server to tell it what to do, and they rarely do much with user-input except send it back to the server where all the important work is done.

Sure the HTML5 <video> tag was sort of neat, but 25 years earlier, I was running a shop of talented developers delivering interactive full-screen video as part of software training titles. And it ran smoothly on painfully underpowered 25MHz 486DX PCs, no less. Now we can do video! Again! In a dumb terminal web browser! Exciting!

Meanwhile, desktop PC hardware has continued to evolve at a blistering pace. Today’s average corporate desktop workstation is as powerful as the supercomputer Lawrence-Livermore National Laboratory used in the mid-90s to simulate nuclear weapons. Yet, apart from running Excel or Outlook, mostly they’re idle, chugging through clumsy web-based applications like a commodity dumb terminal from the 70s.

Let’s Pretend This Doesn’t Suck

Mainframe developers have a big advantage over web developers: nobody really likes using green screens, so nobody is surprised by the terrible user experience they deliver. On the other hand, the advanced display capabilities of modern web browsers have been leveraged by successful, single-purpose companies like AirBnB, Zillow, and many more, presenting simple, easily-navigated interfaces, colorful photos, and professional design. The browser’s dumb-terminal nature has gone underground. These flashy commercial sites set expectations for browser-based development that no enterprise developer can hope to match. In all likelihood those companies have their own internal enterprise-style systems and challenges, but user expectation is driven by the cutting-edge design of public-facing sites.

Additionally, end-users also still run programs like Excel and Outlook, which handle large amounts of data with relative ease. These, too, set certain expectations about modern computing in areas like response time. This type of interaction is still very difficult to achieve within the context of the many limitations imposed by web app development.

The mismatch between expectation and what enterprise developers can realistically deliver leads to real dissatisfaction for everyone. In some organizations, it’s just the elephant in the room that nobody talks about. In others, there is a lot of talk about lofty “modernization” goals – generally with very limited expectations of the actual outcome.

These translate directly into more wasted enterprise resources. It has been conclusively demonstrated that a dissatisfied user is a less-productive user. It’s common sense that users who dislike their work environment will also contribute to higher turnover rates, which leads to other inefficiencies like higher training costs. Additionally, increased development effort and frustration brings similar inefficiencies.

Software development has been a mainstream career long enough that younger generations have grown up thinking all of this is normal. The children of the Gen X’ers are the new enterprise developers, and as far as I can tell, they are embracing all that sucks about these dumb terminals of the modern era.

What am I talking about here? The rise of the Javascript framework. From a positive perspective, things like Angular are attempts to mask the complexities of building a web app that doesn’t suck. This sounds noble enough, but peek under the hood and you’ll find a rat’s nest of complex and frankly very brittle dependencies (many thousands, in the case of a typical Angular project). (And don’t get me started on the more perplexing fascination newer developers seem to have with clunky, unintuitive command-line utilities…)

From a more measured perspective, these efforts are basically hacks, no matter how well-executed they may be. There are significant problems with the core model of building browser-hosted, web-based enterprise applications, and throwing towering stacks of libraries at it is simply whistling past the graveyard.

(Even more shockingly, the web-app-everywhere mentality is metastasizing. I recently learned that the “infotainment” head-units, aka “stereos”, in current-model GM vehicles use Angular for their application UI. A web browser running a ponderous, complex Javascript MVC framework on overtaxed commodity QNX hardware. Why? Who knows? No, it isn’t enterprise development, but the web app fixation doesn’t get much more ridiculous than that.)

The Blame Game

If you’re old and cranky like me, you quickly find yourself wondering who is to blame for all this pain and inefficiency.

In a very real sense, the browser-as-dumb-terminal is slowly and clumsily mutating into browser-as-mini-OS (consider webasm…). It’s a poster-child for the old saw about design by committee. Every so often, long-overdue changes trickle out of the ivory towers of the W3C, the IETF, or maybe ECMA. Then years pass as the browser companies lurch their way towards compliance. Meanwhile, the millenials hack together new polyfills and patches, adding to the stack of frameworks, libraries, transpilers and bundlers that seek to mitigiate The Suck.

But those bureaucrats aren’t to blame. Consensus is difficult, and the browser companies have proven that without carefully-worded specifications to follow, some marketing dork is going to dream up some goofy new feature and push it out, and then we’ll waste another ten years undoing IE6-style incompatibilities.

Maybe we can blame the rise of the “ops” part of what we currently refer to as dev/ops? After all, in modern enterprise development, absolutely everything is on serious lock-down, and the ops people (formerly “network admins”) usually hold all the keys to the kingdom. I am aware of some enterprise environments that are so locked down that it’s difficult for a developer to even develop anything. Paperwork, permission, constant scrutiny and even outright suspicion as a baseline assumption… the people in the room who know the most about how things really work often face major roadblocks to putting that knowledge to good use.

And yet, they are also not to blame. The dev/ops people I know and work with are generally very talented and smart people. As the saying goes, they’re just doing their job. By their very nature, an enterprise must define policies and procedures, though I often question why they must be so aggressively restrictive. All the same: don’t shoot the messenger.

Let’s blame the policy-makers! When you start following the blame-chain, you quickly realize there is rarely any specific party or parties in an enterprise who deserve that blame. Policies evolve at many levels, and often the problems being discussed here are unintentional side-effects of addressing valid but unrelated concerns. Developers sometimes forget that few enterprises are in the software business. There is an actual line of business out there running, and enterprise development is just one cog in that machine. Policies that make good business sense despite making development more difficult is just a fact of life that will never go away.

Earlier I mentioned that all this fancy new web stuff was pretty exciting to developers, but over the years, developers have been pushed further and further down the food-chain by the “lock-down” situation that now exists in the enterprise world. These days, nobody asks developers much of anything that influences enterprise policy, so it’s hard to take the blame upon ourselves.

It is tempting to blame management, but in most cases, management relies on others for guidance. Does this mean I blame the enterprise architects who advise them? Also tempting (speaking as an architect myself), but not necessarily. It’s human nature to assume if we’ve always done it this way, it’s probably what we want to continue doing. Change is often expensive, and after all, two decades later, the enterprise has massive quantities of blood and treasure invested in web applications – and therein lies the clue.

So who is to blame?

Here’s the challenging part: Nobody.

We’ve Always Done It That Way

In a Computerworld article in 1976, Grace Murray Hopper (the famous inventor of COBOL) was quoted as saying:

…the most dangerous phrase a manager can use is “We’ve always done it that way.”

Two decades after the rise of the enterprise web application, this appears to be the reason we keep chasing our tails, using inferior and limited tools and paradigms to (poorly) service the needs of the enterprises that support us.

In every discussion I’ve had with other developers in other organizations about this problem, we eventually conclude it boils down to simple inertia. (Excluding developers who don’t see this as a problem – but I find they tend to be so heavily focused on web app development, they don’t have much experience with anything else. Not surprising.)

The irony is that enterprise developers are frequently subjected to motivational memes like Who Moved My Cheese? or various process- and productivity-enhancers like Six Sigma, Agile, or CMM. I’ve been through all of these and more, and I’ve talked to many others who have survived similar routines and lived to tell about it, and when the smoke clears, the outcome is consistent: it’s usually a struggle to identify concrete benefits, and the results never match the predicted revolutionary improvements.

But that doesn’t make those ideas wrong or bad. Those ideas never stood a chance, because we’ve learned to systematically ignore the real problem. We basically gave up challenging our core assumptions about how to build and deliver enterprise applications.

Like writing COBOL in the 70s, web apps turned into the way we’ve always done it, and we’re long overdue for a change.

Conclusion

Quite simply, I advocate a return to desktop application development as the default model for internal-use enterprise applications. By this point in the article, this should come as no surprise.

I don’t say this because I’m some grumpy old man pining for the golden days of yore – far from it. Many modern dev/ops concepts are simply amazing productivity-enhancers. The IDEs and other tools we have today are almost ridiculously powerful, as are the computers that run our code, the networks that they use, and the servers at the other end. It is quite the opposite argument: we are literally ignoring or under-utilizing enormously powerful capabilities already present in the enterprise, simply because it’s how we’ve always done it.

Let that sink in. An enterprise with 20,000 users and in-house development probably has an annual IT budget in the tens of millions. Imagine if such an enormous sum was being spent in any other area of the business, yet was provably under-utilizing equipment and capability despite having access to such funding. “We’ve always done it that way” wouldn’t stand a chance, and yet it’s the default attitude in enterprise development when it comes to the web application paradigm.

Change wouldn’t even be terribly difficult or disruptive. Zero-install has been easy for probably 15 years, meaning we don’t face many of the support problems that plagued us in the 90s and early 2000s. And, of course, we shouldn’t ignore the truly beneficial things that have arisen from this fixation on web-based applications. REST APIs and JSON serialization are fantastic tools, and the enterprise already has excellent processes in place to build, deploy, and support them.

My argument is that enterprises need to take off the blinders and expand the tools they permit developers to use. The web browser is great for delivering content to places we don’t control – that is, the general public. And they’re great for truly document-like content. Some uses of Sharepoint are a good example of this. Content Management Systems are an even better example. It’s what they’re actually meant to do.

We tried web apps, and it’s time we admit they suck.

There is a better way, the industry just seems intent on ignoring it.

Comments