Service Locator for Azure Functions V2

We examine an easy-to-use technique to simulate dependency injection for Azure Functions V2.

Code for this article can be found here.

A couple of months ago, I posted a pretty popular article named Reusable Dependency Injection for Azure Function Apps. At the time I was focused on V1 Function apps which are based upon .NET Framework and have been around for several years. I set about using the technique from the article in my own apps, and life was good.

Fast-forward to the end of March, and we’ve internally decided the .NET Framework will eventually become a dead-end for web-based-anything, and that likely includes Azure. If we’re right about that, you won’t find Microsoft openly stating this today – they don’t want to scare off their lucrative enterprise customers (quite reasonably), and the glide-path to obsolescence is likely a long one. But there is a great deal of writing on the wall. The intensity of their focus on .NET Core speaks volumes to us, as do little clues such as VS2017 classifying new .NET Framework projects as “Windows Classic Desktop”. We had therefore already concluded our Functions apps must migrate to V2 at some point (probably sooner rather than later).

First we’ll get the elephant in the room out of the way: as the title openly states, eventually I present code which implements the dreaded Service Locator anti-pattern. If you’re pattern-religious, you may wish to avert your eyes. Of course, in reality, patterns are merely guidelines and should not be treated as final rulings set in stone. Later I’ll explain a bit more about why I think it’s ok here as a stopgap measure.

I didn’t immediately turn to the Anti-Pattern Dark Side. Something about a recent V1 runtime update caused some deployed (but still in development) Functions to fail, so I decided to just roll up my sleeves and migrate them to V2, dependency injection bindings and all. “How hard can it be?”

I remembered seeing this announcement that V2 Functions on Azure had also recently been updated. The deployed runtime corresponds to Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions version 1.0.11. I branched my V1 code, crossed my fingers, and began converting, and almost immediately ran into problems. At that point, I set aside my real application and branched the simplified sample code in the repo from my earlier blog article, still intent on dragging the DI bindings into the Functions V2 world.

First Attempt

Sometimes it’s easier to just edit the csproj files directly, but other times it’s the only way to accomplish something. Such is the case with re-targeting. The first step was to change the compile target from the Functions V1 net461 dependency to the V2 netstandard20 dependency. Since I was already in the project files, I just changed the NuGet references by hand, too. I also had to change the various demo Greeter functions to match ASP.NET Core types. You can see the V2 conversion branch changelog here, but I will briefly list the important changes:

| Location | Change |

|---|---|

FuncInjector.csproj |

<TargetFramework>net461 netstandard2.0 </TargetFramework> |

update Microsoft.Azure.Webjobs.* references to 3.0.0-beta5 |

|

FunctionProject.csproj |

<TargetFramework>net461 netstandard2.0 </TargetFramework> |

update Microsoft.NET.Sdk.Functions reference to 1.0.11 |

|

remove the <ItemGroup> referencing Microsoft.Csharp |

|

GreeterFunction.cs |

change each Task<HttpResponseMessage to Task<IActionResult> |

change each HttpRequestMessage to HttpRequest |

|

change each return req.CreateResponse(...) to return new OkObjectResult(...) |

|

various using statements supporting those changes |

It compiled without a hitch, but running the Function app resulted in the following error message, whether I ran it locally or deployed to Azure:

Method not found: 'FluentBinder<!0> Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Host.Config.FluentBindingRule'1.Bind(Microsoft.Azure.WebJobs.Host.Bindings.IBindingProvider)'.

If you clicked that Github link to look at the V2 conversion changes in the repo, you may notice some of the version numbers don’t match the table above. During my troubleshooting, I determined that if I downgraded to SDK 1.0.10 and webjobs 3.0.0-beta4, the Function app does correctly run locally. However, it always crashed on Azure because the runtime on Azure isn’t backwards compatible. I actually tested every SDK/webjob combination that was netstandard20-compliant with the same results.

Clearly the error message meant something had changed in the way custom bindings are created, and since the earlier article’s [Inject] and [RegisterServicesTrigger] features were heavily dependent on that process, I prepared to troubleshoot my way to a fix.

To make a very long story short, I abandoned that approach for two reasons.

First of all, I ran across this Functions wiki page which states: “Custom triggers are not available for Azure Functions,” as well as various Microsoft employee replies to Stack Overflow questions that custom triggers aren’t a supported feature. I think that’s unfortunate, custom trigger bindings clearly do work in V1, but I can see how they could be troublesome to support over the long term.

But more importantly, Microsoft is busily implementing real Functions dependency injection. Reading between the lines in various Github discussions, it sounds like this will be available in the v3.0 runtime. (This will still be Functions V2 – a poor choice of names, if you ask me – why not Functions Core?)

Although I am still very impressed by the registration trigger trick (originally dreamed up by others, as explained in the earlier blog article), I decided to shelve the approach and re-think the problem.

Wrong Things, Right Reasons

In my real project, my Function apps and several ASP.NET Core websites rely on a pretty complex set of libraries which themselves make extensive use of dependency injection. I couldn’t just give up on the idea entirely. Since Functions have that weird static design with parameter-binding-based pseudo-injection, I clearly couldn’t use real DI (otherwise neither of these articles would exist). I considered just waiting for the 3.0 runtime and hacking each Function into it’s own composition root. But cutting-and-pasting loads of service registration code struck me as a particularly nasty fix, and without a lot of extra gyrations I’d lose the option for things like singleton lifetimes for Functions within a single app.

Effectively, I needed to create a reusable Composition Root for each Function app, and since real DI was not in the cards right now, I also needed to suck it up and live with the horrors of a Service Locator until runtime 3.0 delivers us from evil.

I wanted to minimize the impact on my existing Function apps, and I wanted to continue (re)using the service registration extensions provided by the libraries they depended upon. I don’t know what Microsoft’s dependency injection will look like for Functions, but if it’s remotely like any other DI solution, I think my interim solution should be quick and easy to convert, just as it’s quick and easy to convert my V1 [Inject] bindings to this temporary work-around for V2.

Best of all, the solution is very simple. The whole thing is less than 20 lines of code (give or take, depending on what you choose to count).

Registering and Locating Services

The V1 solution in the earlier article and the new V2 solution behave in exactly the same way: they register variations on the Greeter library in different ways to demonstrate the various service registration lifetimes. And, in fact, the Library project in both solutions (where the Greeter implementations live and where dependency injection service registration extensions live) are absolutely identical.

Before I go into how the service locator library works, I want to illustrate how the new system works from the viewpoint of the consuming Function app. In the V1 version, each [Inject]-dependent Function pointed to custom [RegisterServicesTrigger] Functions. Here are the V1 Functions that demonstrate a transient service:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

[FunctionName("GreeterTransient")]

public static async Task<HttpResponseMessage> Run5(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get")] HttpRequestMessage req,

[Inject("RegisterTransient")] IGreeter greeter)

{

return req.CreateResponse(greeter.Greet());

}

[FunctionName("RegisterTransient")]

public static void Config4([RegisterServicesTrigger] IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddGreeterTransient();

}

In the Functions V2 work-around, services are registered by a class that implements the IServiceRegistration interface. This is the new transient service registration class. Note that it is not static – it isn’t a Function implementation of any kind.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public class RegisterTransient : IServiceRegistration

{

public void RegisterServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddGreeterTransient();

}

}

And this is how a Function declares a dependency on that service registration, then requests services from our locator library:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

[FunctionName("GreeterTransient")]

public static async Task<IActionResult> Run5(

[HttpTrigger(AuthorizationLevel.Anonymous, "get")] HttpRequest req)

{

var services = GetServiceLocator<RegisterTransient>();

var greeter = services.Get<IGreeter>();

return new OkObjectResult(greeter.Greet());

}

As you can see, the usage pattern is fast and easy to implement, particularly in a V1-to-V2 scenario, and personally I can live with the dreaded anti-pattern knowing that real DI is in the pipeline.

It’s probably worth explaining that GetServiceLocator<T> is actually from a static class in the service locator library we’ll see in the next section. I used the C# 6.0 using static directive to cut down on the noise, saving us the need to prefix the method call with the class name.

How It Works

The sample code includes a netstandard20 library named FuncServiceLocator. It is comprised of three simple files: IServiceRegistration, ServiceLocator and ServiceLocatorFactory.

The interface that must be implemented by the Function app’s service registration classes defines just one method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace FuncServiceLocator

{

public interface IServiceRegistration

{

void RegisterServices(IServiceCollection services);

}

}

The ServiceLocator object that the Function apps use to request their dependencies is comprised of an internal constructor and a single Get<T> method. There’s nothing fancy here – a new DI ServiceCollection is created, and the service registration class is given the opportunity to register its dependencies. Then the ServiceCollection is processed and the resulting ServiceProvider is stored. The Get<T> method is just a simple wrapper around the GetRequiredService<T> method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

using Microsoft.Extensions.DependencyInjection;

namespace FuncServiceLocator

{

public class ServiceLocator

{

private readonly ServiceProvider provider;

internal ServiceLocator(IServiceRegistration serviceRegistration)

{

var serviceCollection = new ServiceCollection();

serviceRegistration.RegisterServices(serviceCollection);

provider = serviceCollection.BuildServiceProvider();

}

public T Get<T>()

{

return provider.GetRequiredService<T>();

}

}

}

Last but not least, the ServiceLocatorFactory class does all the heavy lifting with its single GetServiceLocator<T> method. The generic type must be a class that implements IServiceRegistration. If that class is not already present in the internal collection, it is instantiated and stored. In this way, we ensure that service registration only happens once if multiple Functions within the same app share the same service registration processes (which has been the most common use-case in my live apps). As shown above, instantiation also executes the service registration process. The result is returned to the Function app, where it can be used to obtain references to desired services.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

using System;

using System.Collections.Concurrent;

namespace FuncServiceLocator

{

public static class ServiceLocatorFactory

{

private static ConcurrentDictionary<Type, Lazy<ServiceLocator>> ServiceCollections = new ConcurrentDictionary<Type, Lazy<ServiceLocator>>();

public static ServiceLocator GetServiceLocator<T>() where T : IServiceRegistration, new()

{

return ServiceCollections.GetOrAdd(typeof(T),

f => new Lazy<ServiceLocator>(() =>

{

return new ServiceLocator(new T() as IServiceRegistration);

})).Value;

}

}

}

We’re done, right? Not so fast…

Fun With Beta Software

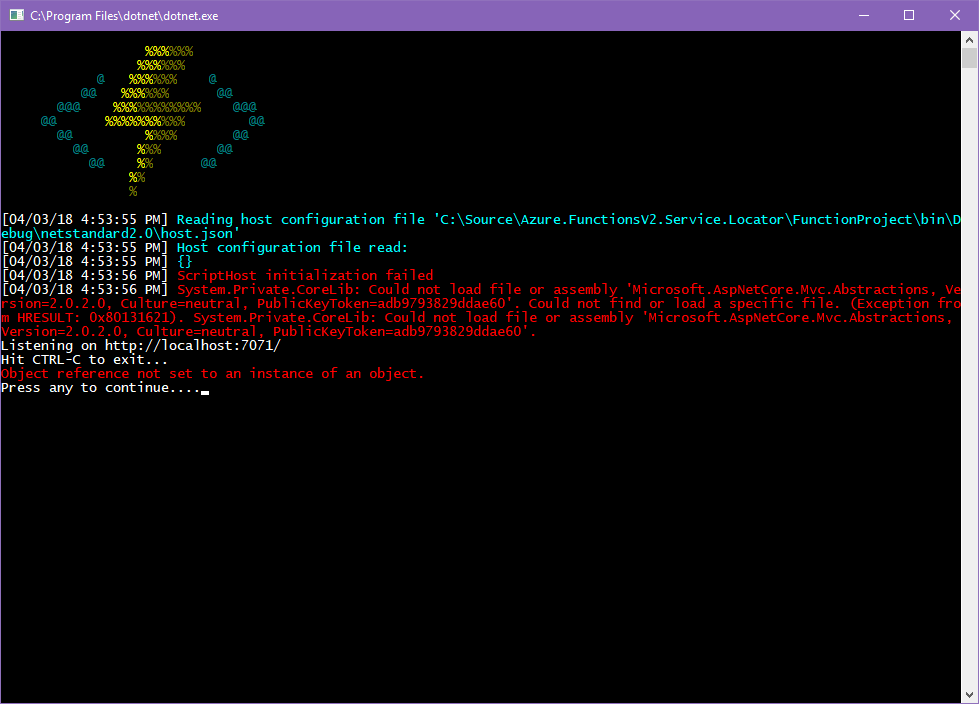

I was pretty happy with this little hack, so I was very disappointed when I hit F5 and was rewarded with:

Could not load file or assembly 'Microsoft.AspNetCore.Mvc.Abstractions, Version=2.0.2.0, Culture=neutral, PublicKeyToken=adb9793829ddae60'.

If I’m reading the tea leaves correctly, updates to the Visual Studio Extension “Azure Functions and Web Jobs Tools” isn’t completely in sync with the Functions V2 runtime releases. Update: Confirmed, the extension is currently not in sync. Open Github bug tracking here.

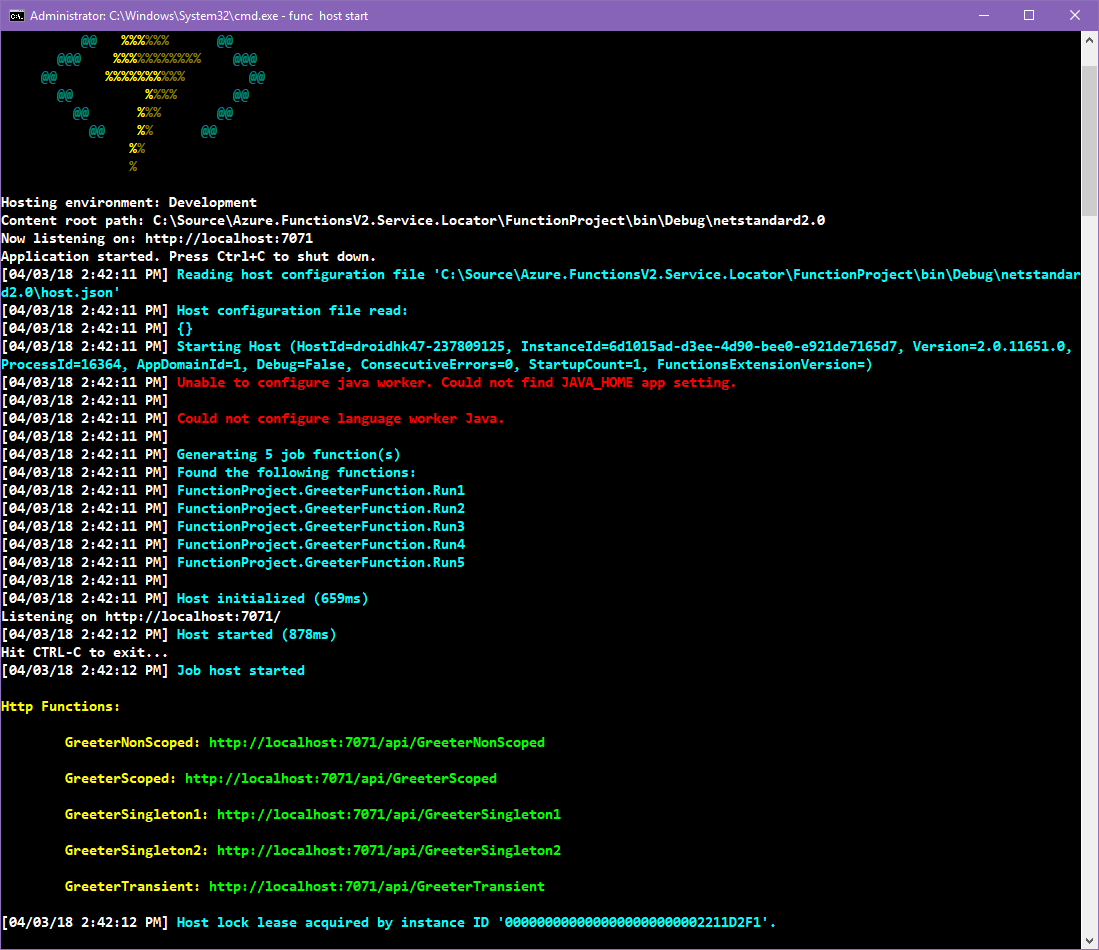

To make another fairly long story short, the solution was to launch the Function app manually from the command-line (is it 1990 yet?) with the Functions Core Tools CLI. This was sort of annoying since it also required me to install another command-line package manager I’ve been trying to avoid, namely npm, dragging an unwanted node.js installation along with it. Luckily there is an open issue around this, Microsoft recognizes requiring non-node developers find, install, and use a “foreign” packaging tool just for this one dependency is not an optimal experience.

The CLI is added to the path, so func can be run from anywhere. I opened a command prompt at the “content root path” for the Function app, which in this case was:

C:\Source\Azure.FunctionsV2.Service.Locator\FunctionProject\bin\debug\netstandard2.0

From that location, merely execute the command func host start, and we’re up and running!

I won’t waste time demonstrating that it works. The test cases are exactly like the tests in the earlier article, with one exception: .NET Core is so much faster than .NET Framework, I couldn’t get the GreeterNonScoped demonstration to show two different timestamps no matter how many times I re-ran the request!

Moreover, the Function app also works perfectly when it is deployed to Azure.

Conclusion

Relying on the Service Locator anti-pattern isn’t something you ought to make a habit of, but in this case it gives us a reasonable stand-in until a future Functions V2 runtime adds real dependency injection support. Hopefully you’ll find it useful in your own experimentation with Functions Core… er, Functions V2!

Comments