Cross-Platform Native Library Loading

How to use unmanaged native cross-platform libraries from a single .NET binary.

In the early 90s, I was managing a software engineering department for a multimedia training company. We were a Microsoft shop, but some of our media creation people had cool SGI machines and there were other Unix boxes floating around. We were just starting to think about the Web (we usually capitalized it back then), and I was lucky enough to get my hands on a late-alpha of this new language called Java. Fast forward to the release in 1996, and Sun was proudly proclaiming the era of “write once, run anywhere” had finally arrived. It didn’t take too long for developers to start using the phrase “write once, debug everywhere”.

Since its inception, .NET Core has been a cross-platform product. I haven’t yet had much serious need for that capability, but I’ve been meaning to get in there and play around with it at some point. While planning another series of articles, I decided to include simple console-based demos that will require more control than .NET offers in the System.Console class. A popular library for this type of thing is “curses” and more specifically the newer, slightly larger API of the “ncurses” library. The original dates back to BSD Unix around 1980 and it has been ported to practically every OS. It is certainly readily available for the three main .NET Core targets: Windows, Linux, and Mac OSX. While my future articles don’t have anything to do with cross-platform development, I quickly found myself thinking about it while researching the various .NET-friendly curses libraries. Some were quite old, some had Mono dependencies (doing cross-platform .NET before it was cool), some had design decisions that I found puzzling, and they were all a bit inflexible.

A few days later I found myself staring at a blank solution, preparing to write what would become dotnet-curses.

Cross-Platform Runtime Decision

When you build and prepare a .NET project for deployment (a process Microsoft now calls “publishing”), you must decide whether the program will depend upon a .NET runtime installed on the machine, or whether you create a “Self-Contained Deployment” or SCD (older Microsoft docs sometimes also call these “self-contained applications”).

Currently SCDs are enormous – they copy the entire .NET stack into your publishing folder along with your app binaries. This is often around 60MB depending on which packages you’re using. Microsoft is working on a variation of the Mono Linker that should trim this to only include the specific files you need, but this is not a great option unless you’re shipping a product so large that a 60MB runtime is inconsequential. On the other hand, an SCD should always work, because every possible dependency is dumped into one giant folder.

Relying on an installed .NET runtime is normal for those of us accustomed to the Windows .NET Framework world. Most of the time, .NET was always just there and ready to use. Obviously, this isn’t the case in the Mac OSX and Linux worlds. If you’re planning a commercial product, you’ll have to either consider dealing with installation yourself, or decide whether your userbase will be willing to do this. Fortuantely Microsoft has a simple, automated installer for Mac OSX. Unfortuantely, Linux installation is the typical mess of terminal apt-get commands, the instructions can vary considerably according to the distro and even the individual point-release you’re on, and when something goes wrong, things can get complicated quickly.

For development scenarios (testing your own cross-platform applications) the framework-dependent model clearly makes sense.

This page is where you download the Mac OSX .NET runtime installer.

Although there is an equivalent Linux page here, there are much better instructions with far more distros and versions listed in the prerequisites documentation on this page. While setting up my Linux VM, I tried to fudge it a little: I was originally running a release that was 0.1 ahead of the supported versions listed – it didn’t work and I don’t recommend it. Unless you can’t avoid it, stick to a specific version listed.

Cross-Platform Build-Target Decision

The other decision when you’re publishing your project is whether to target a specific OS, or stick with the “portable” binary. It’s pretty self-explanatory, although to target a specific OS, you have to jump through some hoops by adding Runtime Identifiers to your project file, then create a publish profile that targets the RIDs. I will only briefly discuss this approach in the next section, since working with native libraries from portable binaries is the focus of this article. (If your build targets a specific OS, you don’t really need the flexible runtime loading of native libraries that we’re going to discuss.)

There isn’t much to say about building the portable binaries. The files that wind up in the publish folder get deployed to whatever OS you choose. (Linux and OSX require an extra step to assign execution permissions which I’ll cover later.)

Everyone Curses Differently

For a couple of days, I thought I might use Raymond Nowley’s csharp-curses library. It has been in recent, active development, and I liked the approach he took to wrapping the native ncurses library. However, I noticed a lot of Windows developers expressing some confusion about how to get started with the library. Raymond told me he normally works in Linux so he hadn’t really explored the problem. By the time we had started talking, I had already decided to write my own library, but I did show him the RID approach described here.

First, the csproj is modified to add a <RuntimeIdentifiers> node which specifies the RIDs the project can target. Microsoft recommends using the most generic RIDs that will work for your project (there are variations on these that specify individual OS versions, sometimes even including patch releases).

1

<RuntimeIdentifiers>win-x64;linux-x64;osx-x64</RuntimeIdentifiers>

After that, three more lines are added which declare a build-time constant based on the RID targeted by the build process:

1

2

3

<DefineConstants Condition="'$(RuntimeIdentifier)' == 'win-x64'">$(DefineConstants);RUNTIME_WINDOWS</DefineConstants>

<DefineConstants Condition="'$(RuntimeIdentifier)' == 'linux-x64'">$(DefineConstants);RUNTIME_LINUX</DefineConstants>

<DefineConstants Condition="'$(RuntimeIdentifier)' == 'osx-x64'">$(DefineConstants);RUNTIME_OSX</DefineConstants>

This is necessary because, unfortunately, the various ncurses native libraries have different filenames on different platforms. On Windows, the file is named libncursesw6.dll. There are several names on Linux, but the most common seems to be libncurses.so.5.9 (where 5.9 is the version). Mac OSX currently deploys with libncurses.5.dylib but they also create a symlink to the latest version that is always named libncurses.dylib.

The normal .NET P/Invoke platform interop approach to calling native libraries is to pass the library filename to a [DllImport] attribute decorating a method with a matching signature. The class and the method must be static, and that filename must be defined at runtime (since it is used in the attribute). When I first used Raymond’s library, it was configured for the Linux curses filename:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public static class NativeMethods

{

const string cursesLib = "libncurses.so.5.9";

[DllImport(cursesLib)]

public static extern int addch(int ch);

// etc...

}

For OS-targeted builds, the cursesLib constant was replaced by this RID test:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

#if RUNTIME_OSX

const string cursesLib = "libncurses.dylib";

#elif RUNTIME_LINUX

const string cursesLib = "libncurses.so.5.9";

#else // RUNTIME_WINDOWS

const string cursesLib = "libncursesw6.dll";

#endif

This way, as long as your published build targeted the right OS, the correct library name is provided to the [DllImport] attribute and the app will work on the target OS. This kept me fat and happy while I began to familiarize myself with curses programming.

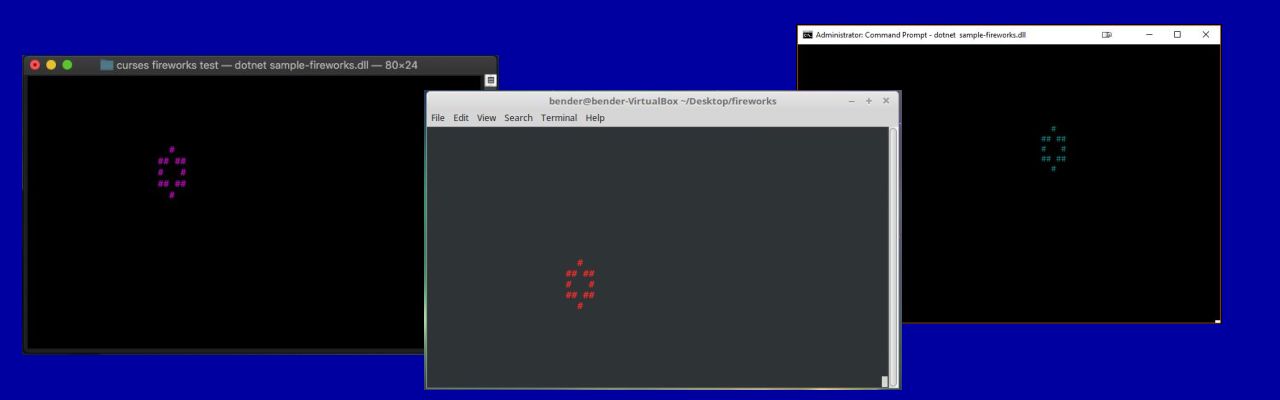

Fireworks and Exports

I remembered seeing a cool port of an old curses demo that drew colored fireworks in the console window. It was implemented in a different .NET curses library, Robert N’s CursesSharp. I decided wiring it up to Raymond’s csharp-curses library would be a fun exercise. However, I ran into a pair of curses properties used by the demo that were not yet exposed by the csharp-curses library: LINES and COLS. These hold the screen dimensions when the curses library is initialized.

It turns out that LINES and COLS are exported from the native curses library as global variables which are not supported by .NET’s current interop model (I have opened a github issue to discuss adding this capability). CursesSharp exposes these with a native shim DLL, and csharp-curses simply doesn’t have a good way to solve this problem.

I thought to myself, “How hard can it be?”

Win32 to the Rescue

I already had the RID-based code to get the correct library name, so I dusted off my Win32 C-API knowledge and added this to csharp-curses:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

public static int Lines => GetInt("LINES");

public static int Columns => GetInt("COLS");

[DllImport("kernel32")]

private static extern IntPtr GetModuleHandle(string fileName);

[DllImport("kernel32")]

private static extern IntPtr GetProcAddress(IntPtr module, string procName);

private static int GetInt(string symbolName)

{

var handle = GetModuleHandle(cursesLib);

var symaddr = GetProcAddress(handle, symbolName);

return (int)Marshal.PtrToStructure(symaddr, typeof(int));

}

It worked like a charm! The handle should probably be cached, and if you know Win32 you might wonder why I didn’t call LoadLibrary (answer: P/Invoke would have already loaded the DLL by the time GetInt is called), but my next big trick was to figure out how to do the same thing on Linux and OSX. Again… how hard can it be?

A bit of research showed that both operating systems (indeed all Unix/POSIX OSes) rely on dlopen to find or load a library, dlsym to fetch the address of an exported symbol, and dlfree to release the library, and these are in a library named libdl. Sometimes. It turns out that OSX does indeed store these in libdl.dylib but Linux often uses libdl.so.2, and sometimes other Linux distros use other names – there is no standard.

This bit of madness led me to this long Microsoft CoreFX github discussion about (drum-roll) cross-platform loading of native libraries: the reason we’re here today. And there is a real gem buried in that thread: the prototype project by Eric Mellino, NativeLibraryLoader, which is the basis for how this will be supported in a future .NET release (possibly and hopefully .NET Core 2.2, and probably as part of the interop Marshal class, in case you don’t feel like reading the whole thread).

What NativeLibraryLoader does not fix is the problem of dlopen and dlsym living in inconsistently-named libraries. It is discussed in that thread, and there are plans to deal with it at the same time this other new interop support is added, but that’s a problem which can only be addressed by the .NET internals. However, part of the prototype involved trying to load a list of library names, and that does solve the problem of inconsistent names for the ncurses libraries: now I could test for all the variations, however ridiculous they might be. Perhaps more importantly, it also uses an interesting delegates-based technique to defer wiring up a static method to an exported library call that isn’t resolved until runtime. It’s almost black magic.

How could I not write my own curses library with this kind of cool trickery staring me in the face?

I Hope You Like Typing

Every good fairy tale teaches you that black magic carries a high price, and NativeLibraryLoader is no exception. In all of the other .NET curses libraries, exposing the native addch function looks like this:

1

2

[DllImport(libraryName)]

public static extern int addch(int ch);

However, in order to wire up addch with a library call that isn’t resolved until runtime, NativeLibraryLoader requires this rather more complex declaration:

1

2

3

4

[UnmanagedFunctionPointer(CallingConvention.Cdecl)]

private delegate int type_addch(int ch);

private static type_addch sym_addch = LoadFunction<type_addch>("addch");

public static int addch(int ch) => sym_addch(ch);

The code isn’t too difficult to follow. A delegate is declared which matches the target function’s signature. It is followed by a static field of that delegated type which is initialized by a function that loads a symbol by name (the target function) and casts it to the delegated type. Finally, a public method is declared, again matching the target function signature, which is just a pass-through invocation of the delegate.

The technique is sort of obvious in hindsight, but I still think it’s pretty clever. Unfortunately it’s a lot of typing that doesn’t lend itself well to cut-and-paste (and for some bizarre reason, Microsoft removed macro capabilities from Visual Studio many years ago). This isn’t too bad if you’re dealing with a relatively limited native API, but the ncurses library has approximately 600 functions. Some of them are internal, but the bulk of them are not. Currently the dotnet-curses project exposes 91 of these functions, plus the LINES and COLS variables mentioned earlier.

Notice the [DllImport] version specifies the library name, but in the NativeLibraryLoader version the library name is nowhere to be found. This was one of the benefits of this library that I mentioned earlier: the ability to attempt to load from a list of library names.

The Great Library Search

A closed issue on the NativeLibraryLoader repository asks for an example of how to use this, and Eric replied with a link to this code in another repository he owns. In a nutshell, it produces an array of possible library filenames based on the runtime operating system reported by .NET. That list is passed to his NativeLibrary class which attempts to load each name until one succeeds (otherwise it throws an exception).

My curses library naming problems were solved! I added this to dotnet-curses:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

private static NativeLibrary lib = FindLibrary();

private static NativeLibrary FindLibrary()

{

string[] names;

if (RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.Windows))

{

names = new[] { "libncursesw6.dll" };

}

else if (RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.Linux))

{

names = new[]

{

"libncurses.so",

"libncurses.so.5.9"

};

}

else if (RuntimeInformation.IsOSPlatform(OSPlatform.OSX))

{

names = new[] { "libncurses.dylib" };

}

else

{

throw new Exception("Unsupported OSPlatform, can't locate ncurses library.");

}

NativeLibrary lib = new NativeLibrary(names);

return lib;

}

It worked like a charm on Windows and OSX … but there was still that issue of Linux hiding the library-loader functions in files with inconsistent names. As it stands today, the NativeLibraryLoader project assumes OSX and Linux use a library named libdl consistently (there is an issue about this). However, my Linux VM was using a file named libdl.so.2. My solution was to split the libdl class into libdl_linux and libdl_osx classes and modify the LibraryLoader class to treat Linux and OSX separately. It isn’t ideal but it will work well enough for my purposes until Microsoft improves the situation in .NET Core. (Because of these changes, dotnet-curses has a completely separate copy of NativeLibraryLoader. I may consider a PR to update the real NativeLibraryLoader, but I suspect Eric considers it a throw-away given that we know similar but expanded capabilities are in the pipeline for .NET Core.)

More Naming Shenanigans

Eventually I’d like to publish dotnet-curses as a NuGet package, so I was a little uncomfortable hard-coding curses library names into the project without any easy way for a library-consumer to expand upon or even completely replace the list. I addressed this by moving the default names into a separate class with virtual properties that a consumer can override. It looks like this (without comments):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class CursesLibraryNames

{

public virtual bool ReplaceWindowsDefaults => false;

public virtual List<string> NamesWindows => new List<string> { "libncursesw6" };

public virtual bool ReplaceLinuxDefaults => false;

public virtual List<string> NamesLinux => new List<string> { "libncurses.so.5.9", "libncurses.so" };

public virtual bool ReplaceOSXDefaults => false;

public virtual List<string> NamesOSX => new List<string> { "libncurses.dylib" };

}

At start-up, the library uses reflection to look for a class derived from this default class and either adds the filenames in the derived class to the defaults, or ignores the defaults and only uses the derived class list(s). In the curses world, it is relatively safe to attempt to load versions which were unknown when the library was built – curses releases are very infrequent and they tend to be additive. A derived class to add the name of a Windows version 7 DLL and completely replace the Linux list would look like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public class AdditionalLibraryNames : Curses Library Names

{

// add to the Windows defaults

public virtual List<string> NamesWindows => new List<string> { "libncursesw7" };

// replace Linux defaults

public override bool ReplaceLinuxDefaults => true;

public override List<string> NamesLinux => new List<string> { "libncurses.so.7" };

}

This actually led to a nasty TypeInitializer exception that was difficult to diagnose. The short version is that it’s related to the sequence that C# initializes static fields and the fact that this delegates-based method references the library handle before the library reference is resolved. The solution was to move the library reference into a separate static class from the curses library delegates.

Write Once, Run Anywhere

That covers all of the interesting parts of this little cross-platform journey, but I’d like to share a few links and cover a few points for anyone new to either the Unix world or curses programming.

I mentioned earlier that Linux usually ships with an ncurses implementation, and OSX always does. For Windows, you can download it from Thomas Dickey’s site (the current ncurses maintainer) from the MinGW links. Put it into a folder that is in your system PATH variable or your app deployment folder. That’s all it takes. A very basic, high-level intro to curses programming is here and Eric Raymond wrote a much more detailed article about it here.

Finally, if you’re preparing to test this kind of cross-platform development on OSX or Linux for the first time, you should know that you must grant “execute” permissions to the main application binary before you can, well, execute it. This is easy enough. Open a terminal window, cd to the location of the file, and use the chmod command to grant execute permissions. For the fireworks demo, the command would be chmod +x sample-fireworks.dll.

You may have noticed the “dll” extension on the main executable. You use the dotnet command to execute portable applications on all platforms: dotnet sample-fireworks.dll starts the show (press ESC to exit).

As always, I hope you found this interesting and useful, and I look forward to your comments and ideas.

Comments