Serialization for Encapsulated Enumeration Classes

Transparent JSON serialization of classes using the encapsulated enumeration pattern.

The enum keyword is one of those language features that seems like a great idea until you’ve lived with a whole bunch of them, each defined by different developers over a very long period of time.

I recently designed a modern replacement for a sprawling line-of-business system that is approaching 20 years in service. Much of the data used by that system comes from even older mainframe applications and databases which rely upon an enormous number of single-character code values. These were translated into various user-friendly on-screen descriptions, and the code values themselves drove various business rules behind the scenes. In an attempt to make the business rules readable, the old system added a third representation of these values by mapping the single-character database codes to various enum members. As the system grew and changed and developers came and went, sometimes the enums were used, sometimes declared constants were used, and sometimes hardcoded constants were used. Not everyone handled the mapping the same way. Sometimes you got mapping only in one direction or the other. I wanted to discourage this in the next 20-year lifecycle.

There is a fairly old pattern that goes by variations on the name “encapsulated enumeration.” The idea is to organize your enumeration values into full-blown (but simple!) classes that more cleanly and completely express what the enumerations are meant to represent. I first saw this in a 2003 edition of Dr. Dobb’s, though I suspect the idea is even older. It isn’t a ground-breaking concept, but if you’re dealing with systems of any complexity, you’ll welcome the consistency it adds to your code base. Encapsulation is handy, but my article title also mentions serialization: the encapsulating classes don’t serialize as cleanly as I liked, and fixing that transparently turned out to be slightly more work than I anticipated.

For those of us in the .NET world, Microsoft offers a reasonable starting point in their recent microservices architecture e-Book. In this article, I’ll expand on that example significantly.

Code for this article can be found on GitHub at MV10/Serializing.Encapsulated.Enumerators.

Going Generic

The Microsoft Enumeration class is a base implementation from which individual enumeration classes are derived. The class is pretty simple: a numeric Id and a corresponding Name, a ToString override, and some comparison support. If you’re familiar with the enum keyword, you may know that you can declare the enumeration to store the values as one of several numeric types. This isn’t too commonly used, but it’s already a limitation imposed by a class that is supposed to bring flexibility. Additionally, there is no reason to restrict enumerations to numeric representations.

As a result, my first deviation from the Microsoft example was to implement the class with generic support for the identifier. I also renamed the Id property to Code and the Name property to Description. I changed the constructor visibility to public for reasons that will be explained later, and the properties have protected set to support deserialization we’ll add later.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

public class Enumeration<T> : IComparable

{

public T Code { get; protected set; }

public string Description { get; protected set; }

public Enumeration()

{ }

public Enumeration(T code, string description)

{

Code = code;

Description = description;

}

public override string ToString() => Description;

public static IEnumerable<E> GetAll<E>() where E : Enumeration<T>, new()

{

var type = typeof(E);

var instance = new E();

var fields = type.GetTypeInfo().GetFields(BindingFlags.Public | BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.DeclaredOnly);

foreach (var info in fields)

{

var locatedValue = info.GetValue(instance) as E;

if (locatedValue != null) yield return locatedValue;

}

}

public override bool Equals(object other)

{

var otherValue = other as Enumeration<T>;

if (otherValue == null) return false;

var typeMatches = GetType().Equals(other.GetType());

var valueMatches = Code.Equals(otherValue.Code);

return typeMatches && valueMatches;

}

public override int GetHashCode()

=> Code.GetHashCode();

public int CompareTo(object other)

=> (other.GetType() != GetType()) ? -1 : CompareTo(other as Enumeration<T>);

}

The result is a more flexible representation that can handle numeric identifiers or string identifiers, which is much more useful in the real world.

A Simple Example: Yes and No

It’s common to work with databases that store a “Y” or “N” indicator in a single-character field to represent “Yes” and “No”. The limited set of code values and the universiality of the concept makes this a great candidate for a reference implemenation of an enumeration class.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public class EnumYesNo : Enumeration<string>

{

public static EnumYesNo Yes = new EnumYesNo("Y", "Yes");

public static EnumYesNo No = new EnumYesNo("N", "No");

public static EnumYesNo Undefined = new EnumYesNo("", "");

public EnumYesNo() : this(Undefined.Code, Undefined.Description)

{ }

public EnumYesNo(string code, string description) : base(code, description)

{ }

}

With just a few lines of code, we’ve created a flexible, fully-encapsulated enumeration with convenient code/decode capability. The enumerated code values and their plaintext descriptions are implemented as static members. I have learned that Undefined is a very handy convention – use it when you declare an EnumYesNo variable or property but don’t yet know what the value should be (or if there will be any value at all).

You wouldn’t want to burden enumeration classes with business rules, but in some cases (like this example) helper functions can make your code even cleaner. It’s natural to speak of Yes/No values in Boolean terms, so let’s add a few more lines to make this class even more useful on a day-to-day basis.

1

2

3

4

5

public static EnumYesNo FromBool(bool value) => (value ? Yes : No);

public bool IsYes => Code.Equals(Yes.Code);

public bool IsNo => Code.Equals(No.Code);

public bool IsUndefined => Code.Equals(Undefined.Code);

Consider how clean this makes the application code.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var EliteStatus = EnumYesNo.FromBool(QueryCustomerIsElite(customerId));

CustomerViewModel.EliteStatus = EliteStatus.Description;

if(EliteStatus.IsYes)

{

Flight.UpgradeToFirstClass();

}

else

{

Flight.DowngradeToCattleClass();

}

Your Data Deserves Better Than That

In the first line of the example above, we imagine QueryCustomerEliteStatus returns a Boolean. But in the real world it’s more likely we’ll have to consume the “Y” or “N” values stored by the database (or in my work scenario, values expected by and returned from the mainframe). This is an obvious candidate for serialization support. My system reads and writes JSON data, so we’ll implement this with the ubiquitous Newtonsoft JSON.NET.

In my first pass, I implemented a JsonConverter (which I’ll get to later), and the ReadJson method which turns a string into a matching enumerator object originally required each enumerator class to add a method that looked like this:

1

2

3

4

public object DeserializeJson(string jsonValue)

{

return GetAll<EnumYesNo>().Where(n => n.Code.Equals(jsonValue)).FirstOrDefault();

}

Since C# is not a “duck-typed” language, it is necessary to populate generics (like this invocation of GetAll<T>) using a static type that is known at runtime. There are ways to avoid this using the new(ish) dynamic keyword and the underlying DLR, but I didn’t want to pull in those dependencies, and they can exhibit performance issues. After just a few minutes I was able to serialize and deserialize my enumeration classes using only the Code values, just as the database and mainframe require.

However, when it came time to define all of my business-domain enumeration classes, cutting/pasting/tweaking this code over and over felt very wrong. It was time to bite the bullet.

First Bite of a Shiny Silver Bullet

Bite the bullet. Silver bullets. Shiny silver. Reflective… Reflection! Get it? I’m a programmer, not a stand-up comic.

The solution was to implement a single deserializer that uses reflection to find a match. Reflection also has a reputation for performance issues but in my experience it isn’t nearly as bad as the performance hit from using the DLR. (Virtually all off-the-shelf serialization options rely on reflection, for obvious reasons.)

The class derived from JsonConverter implements three methods, and classes that depend upon it reference the converter with a class attribute. The converter needs the dependent classes to implement a simple interface which is also shown below.

1

2

3

4

5

public interface IEnumerationJson

{

object ReadJson(string jsonValue);

string WriteJson();

}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public class EnumerationJsonConverter : JsonConverter

{

public override bool CanConvert(Type objectType)

=> (objectType == typeof(EnumerationJsonConverter));

public override object ReadJson(JsonReader reader, Type objectType, object existingValue, JsonSerializer serializer)

{

string jsonValue = JToken.Load(reader).ToString();

var enumClass = existingValue as IEnumerationJson;

return enumClass.ReadJson(jsonValue);

}

public override void WriteJson(JsonWriter writer, object value, JsonSerializer serializer)

{

var enumClass = value as IEnumerationJson;

JToken.FromObject(enumClass.WriteJson()).WriteTo(writer);

}

}

The converter doesn’t do much by itself, the real work is done in the classes that use the converter. ReadJson just grabs the string value (for EnumYesNo, this would be a “Y” or “N” value), casts the target object as an IEnumerationJson type, then passes along the value for processing by the dependent class. All the hard reflection work is done by the implementation code shown in the next section. The same three-step process takes place in the converter’s WriteJson implementation.

Enumeration Deserializer

Next, we decorate Enumeration<T> with the converter attribute, then we tackle the larger task of implementing the read/write methods required by the IEnumerationJson interface. Change the method signature as follows.

1

2

[JsonConverter(typeof(EnumerationJsonConverter))]

public class Enumeration<T> : IEnumerationJson, IComparable

Next we add the implementations of the two interface methods called by the converter.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public virtual object ReadJson(string jsonValue)

{

var type = GetType();

var instance = Activator.CreateInstance(type);

var fields = type.GetTypeInfo().GetFields(BindingFlags.Public | BindingFlags.Static | BindingFlags.DeclaredOnly);

foreach (var info in fields)

{

var locatedValue = info.GetValue(instance);

if(locatedValue != null && locatedValue.GetType().IsAssignableFrom(type))

{

var serializedValue = info.FieldType.GetMethod("WriteJson")?.Invoke(locatedValue, null);

if (serializedValue != null && ((string)serializedValue).Equals(jsonValue)) return locatedValue;

}

}

return null;

}

public virtual string WriteJson()

=> Code.ToString();

You can see that the WriteJson implementation is trivial – JSON data is always string data, so we just return the string value of our user-unfriendly Code value. But ReadJson is another matter.

Crucially, when ReadJson is invoked at runtime, GetType() will return the derived class such as EnumYesNo, rather than the Enumeration<T> class where this method is defined. The code retrieves a list of public static declarations. For EnumYesNo this list is the static Yes, No, and Undefined instances of the class. It iterates over that list looking for any entries that are of the same derived type. It compares the WriteJson output to the value passed in by JSON.NET, and if a match is found, that instance is returned. The call to Activator.CreateInstance is the reason our constructors are declared public rather than protected as in the Microsoft version.

This means each individual encapsulation class doesn’t need to handle serialization or deserialization at all. However, by declaring our implementations as virtual we can allow any derived class to override this implementation if necessary.

Incidentally, with a little casting, any part of your application could also use this method to turn a raw data value into an enumeration instance.

1

2

3

string EliteDataValue = QueryEliteFlag(customerId); // returns Y or N

var EliteStatus = (EnumYesNo)EnumYesNo.Undefined.ReadJson(EliteDataValue);

// etc...

Update: An earlier version of this article omitted Undefined in the parsing code shown above. More recently, I have posted this article demonstrating a cleaner approach to parsing.

Test Run

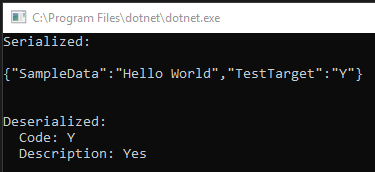

Testing serialization and deserialization is easy enough. This .NET Core console program has a class that referencs our encapsulated enumeration library. We set it up, serialize it to JSON, deserialize the result, and demonstrate that the enumeration code value survived the round-trip.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var WriteValue = new TestData() { TestTarget = EnumYesNo.Yes };

string json = JsonConvert.SerializeObject(WriteValue);

Console.WriteLine($"Serialized:\n\n{json}\n\n");

var ReadValue = JsonConvert.DeserializeObject<TestData>(json);

Console.WriteLine($"Deserialized:\n Code: {ReadValue.TestTarget.Code}\n Description: {ReadValue.TestTarget.Description}");

Console.ReadKey();

}

class TestData

{

public string SampleData = "Hello World";

public EnumYesNo TestTarget = EnumYesNo.Undefined;

}

}

Conclusion

This implementation of the encapsulated enumeration pattern has a number of important benefits. First and foremost, it’s small, simple, and fast. It is easy to create new enumeration classes, and they automatically support serialization with zero additional effort (so far I haven’t found a need to override the base class support). While you’d be hard-pressed to justify this effort for the simple Yes/No example in the article, in real-world use this implementation significantly improves the readability and maintainability of your code and reduces complexity.

I hope you find it useful, or at least interesting. Hit me up in the comments with any questions or thoughts.

Comments