Query Plaintext or Encoded XML with SQL Server

When XML data is stored as text in SQL Server, reading and querying that data requires a few extra steps.

Virtually every developer has worked with XML data in one form or another, but at the end of the 1990s, it was still in the “shiny new toy” category. At the time, I was building a complex financial application which involved a very large amount of varying content, and I designed the system around an XML document format that is still in use nearly 20 years later. The XML was stored in a SQL Server database, and we only extracted a small handful of data elements to store as discrete columns. In effect, I designed a NoSQL-like document database almost ten years before the concept had a name. (We also beat SOAP to the punch for XML-based remote method invocation, and with a lot less ceremony and overhead, but that’s another story.)

In those days, SQL Server didn’t have an XML data type, so we stored the document in a text-based field (originally a SQL text column but later migrated to the ANSI-compliant varchar(max) type). The user worked with the data from a single XML document throughout their session, identified by combinations of the six or seven data elements we extracted to dedicated columns, so there wasn’t any requirement to query against the XML itself.

Fast forward ten years and an external system found a need to store custom data as part of our system’s XML document. The X stands for Extensible, so we simply defined a new node and the other system began storing their information inside ours – we had no need to read, understand, or otherwise touch their data, and another ten years and many millions of rows later, the two systems are still living in harmony.

Recently, someone on the business side approached us about a problem they had discovered. A downstream system hadn’t been sending certain notifications, and there was a need to figure out the impact. Suddenly we needed to query all of that XML data. We’d never converted the column to the SQL XML data type because our use cases didn’t require the functionality, so there was no benefit to the additional processing overhead. Worse, a follow-up request involved extracting data from the custom data stored by the external system – which is when we discovered the external system had always written their custom XML as URL-encoded escape sequences.

Equivalent Scenario

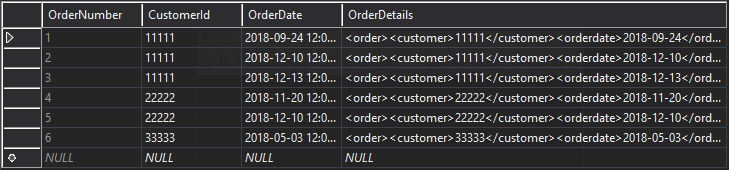

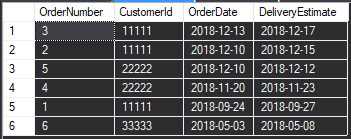

We’re going to reproduce that scenario with a very simple XML document that represents the order history of an online retailer of educational scientific materials. We’ll be working with this OrderHistory table:

1

2

3

4

5

6

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[OrderHistory] (

[OrderNumber] INT IDENTITY(1, 1) NOT NULL,

[CustomerId] INT NOT NULL,

[OrderDate] DATETIMEOFFSET(7) NOT NULL,

[OrderDetails] VARCHAR(MAX) NOT NULL

);

OrderNumber is your typical auto-incrementing identity column, nothing special about that. CustomerId and OrderDate are values that we extract from the XML document for various fast SQL query operations. In reality you’d probably extract more, but that aspect is irrelevant to this discussion. And finally, OrderDetails is our varchar(max) column which stores a text representation of our XML data.

Of greater interest is the XML to be stored:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

<order>

<customer />

<orderdate />

<items>

<item>

<sku />

<description />

<quantity />

<price />

</item>

</items>

<shipping>

<shipping>

<priority />

<deliveryest />

<shipdate />

</shipping>

</shipping>

</order>

The idea is that the application creates the document, populating the customer information, the order submission date, and a list of the items making up the order, then some separate process attaches the shipping information. This mimics the scenario I descrbied in the introduction.

Notice that there are two <shipping> nodes, one nested inside the other. This also mimics what I found in the real-world equivalent to this scenario. This happened because XML always requires a single root node, and the external process happened to assign the same name to their root node that we had created to store their custom data. As we’ll see, it turns out this extra node also makes it a bit easier to set up the query (and for the same underlying reason).

The only other change to complete this scenario is to URL-encode the inner <shipping> XML data provided by the external system:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

<shipping>

<shipping>

<priority></priority>

<deliveryest></deliveryest>

<shipdate></shipdate>

</shipping>

</shipping>

With the XML structures defined, we can insert a handful of sample rows:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

INSERT INTO OrderHistory (CustomerId, OrderDate, OrderDetails) VALUES

(11111, '2018-09-24', '<order><customer>11111</customer><orderdate>2018-09-24</orderdate><items><item><sku>A12345</sku><description>Lil Scamp Home Fusion Learning Lab</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>100.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>2</priority><deliveryest>2018-09-27</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-09-24</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>'),

(11111, '2018-12-10', '<order><customer>11111</customer><orderdate>2018-12-10</orderdate><items><item><sku>B45678</sku><description>Portable Dobsonian Telescope Kit</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>250.00</price></item><item><sku>C87654</sku><description>2019 Astronomy Guide</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>15.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>4</priority><deliveryest>2018-12-15</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-12-12</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>'),

(11111, '2018-12-13', '<order><customer>11111</customer><orderdate>2018-12-13</orderdate><items><item><sku>N76543</sku><description>My First Gene Splicing Lab</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>99.95</price></item><item><sku>D09876</sku><description>Reptile DNA, Assorted</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>21.00</price></item><item><sku>D45678</sku><description>Squid DNA, Giant</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>48.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>3</priority><deliveryest>2018-12-17</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-12-14</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>'),

(22222, '2018-11-20', '<order><customer>22222</customer><orderdate>2018-11-20</orderdate><items><item><sku>A65432</sku><description>Lil Scamp Fluorosulphuric Acid Homebrew Kit</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>75.00</price></item><item><sku>Q76543</sku><description>Neoprene Gloves, Box of 100</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>9.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>2</priority><deliveryest>2018-11-23</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-11-21</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>'),

(22222, '2018-12-10', '<order><customer>22222</customer><orderdate>2018-12-10</orderdate><items><item><sku>A12345</sku><description>Lil Scamp Home Fusion Learning Lab</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>100.00</price></item><item><sku>Q34567</sku><description>Deuterium-Tritium, 100 Grams</description><quantity>3</quantity><price>10.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>1</priority><deliveryest>2018-12-12</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-12-14</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>'),

(33333, '2018-05-03', '<order><customer>33333</customer><orderdate>2018-05-03</orderdate><items><item><sku>E67890</sku><description>E-Z-Bake Clone Tank</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>185.00</price></item><item><sku>D56789</sku><description>Tyrannasaurus Rex DNA (Guaranteed Viable)</description><quantity>1</quantity><price>125.00</price></item></items><shipping><shipping><priority>4</priority><deliveryest>2018-05-08</deliveryest><shipdate>2018-05-04</shipdate></shipping></shipping></order>');

Remember, the XML shown below is just text as far as SQL Server is concerned.

Cast and Cross Apply

Converting that text data to an XML document simply requires using the T-SQL cast statement:

1

select cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml from OrderHistory;

However, the syntax required to use XML fields isn’t quite as obvious. We’re going to take advantage of a Common Table Expression (CTE) and the cross apply statement. The apply keyword is basically a join statement that supports record sources which join does not, including table-valued functions like the XML nodes function.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

with

parsedorder (CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select CustomerId,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

)

select

CustomerId,

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDateFromXml

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

order by OrderDateFromXml desc;

CTEs produce something similar to a view that only exists for the duration of the query. This CTE clause (the with portion at the beginning) outputs the underlying physical table’s CustomerId column as well as the text-based OrderDetails column after converting it to a strongly-typed fully-parsed XML document. The CTE is named parsedorder and the dependent select statement retrieves data from the CTE which is then joined (via cross apply) with the root node of the XML document column:

1

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

Clearly OrderDetailsXml is the strongly-typed XML document we created in the CTE. The nodes function is unique to the SQL XML data type. It returns repeated instances of nodes matching xpath expression as a recordset in a process Microsoft refers to as “shredding”. The syntax orderxml(r) is meant to represent “table(column)” – not very clear in this case since the entire document is the “table” and //order is the “column”. I tend to use foo(r) since the “column” part is fixed and this syntax feels more like a root node reference than a “table(column)” relationship, in my opinion. In this example, we are retrieving the <orderdate> node, a child of the root <order> node:

1

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDateFromXml

Here we’re passing another xpath expression to the value function – the node name is enclosed in parenthesis and [1] ensures that one and only one result is emitted. Without this, the query parser will throw an error. We also specify the SQL data type (as a string) to which the node value should be converted.

Important: SQL Server uses case-sensitive matching when processing XML node names in xpath expressions!

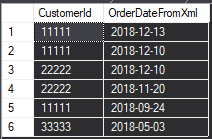

Running that query yields the following results:

Note that we have also used the extracted date value with our order by clause. This is the only place you can reference an aliased column from the select statement because order by is the only clause that is evaluated after the entire resultset is determined. (This is not specific to CTEs or XML, it’s a general SQL limitation.) The inability to reference aliased columns will somewhat complicate things for us in later examples.

Reading Multiple Child Nodes

The XML document can contain multiple <item> nodes under the //order/items path. The basic technique to access these is the same – we create a recordset as a cross apply pseudo-table. However, if we want to access both levels, we need a sub-select. (This could also be accomplished with another CTE.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

with

parsedorder (OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CustomerId,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

)

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

OrderDateFromXml,

itemsxml.r.value('(sku)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemSku,

itemsxml.r.value('(description)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemDescription,

itemsxml.r.value('(quantity)[1]', 'int') as ItemQty,

itemsxml.r.value('(price)[1]', 'money') as ItemPrice

from (

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDateFromXml,

OrderDetailsXml

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

) as orderdata

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order/items/item') itemsxml(r)

order by OrderDateFromXml desc;

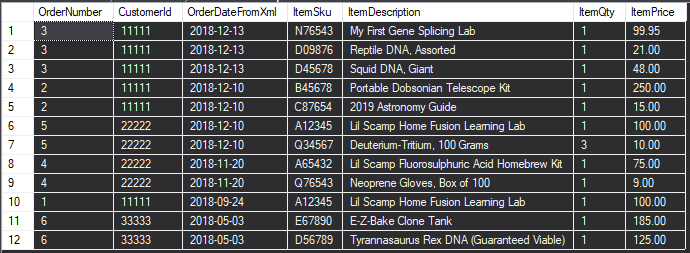

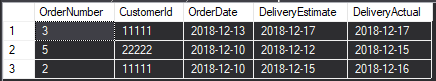

Before we dissect this example, let’s look at the results:

Here we can see that customer 11111 ordered six items on three occasions, customer 22222 ordered four items on two occasions, and customer 33333 placed a single order for two items. Notice also that row 7 has a quantity of 3 – we’ll come back to that shortly.

This query isn’t too hard to understand. The CTE is the same except that we added the OrderNumber identity column, and the query we reviewed in the last section is used as a sub-select which provides the OrderDateFromXml value from the top-level XML. Next it uses cross apply to join those results with another nodes-generated rowset, this time based upon <item> nodes under the //order/items path. This example more clearly demonstrates the “column” concept of the table(column) notation for a cross apply. Here, <item> is the “column” and we’re using the value function to extract nodes under the “column” for each row in the //order/items “table”.

The Alias Limitation

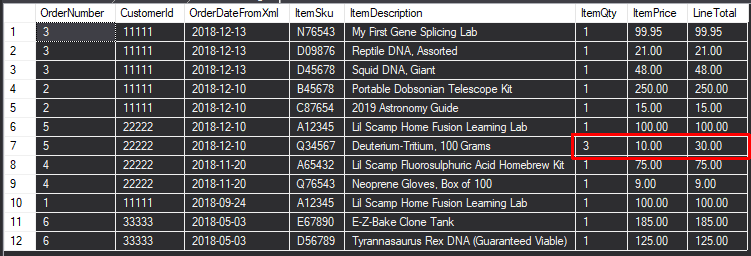

Earlier we noted that aliased columns are only avaialble to the order by clause. An obvious calculation to make for this type of data is to multiply the quantity by the item price. However, we can’t just add that calculation to the select statement:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

with ...

select

itemsxml.r.value('(quantity)[1]', 'int') as ItemQty,

itemsxml.r.value('(price)[1]', 'money') as ItemPrice,

-- parsing fails with two "Invalid column name" errors

(ItemQty * ItemPrice) as LineTotal

from ...

The solution is another sub-select:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

with

parsedorder (OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CustomerId,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

)

select

*,

(ItemQty * ItemPrice) as LineTotal

from (

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

OrderDateFromXml,

itemsxml.r.value('(sku)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemSku,

itemsxml.r.value('(description)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemDescription,

itemsxml.r.value('(quantity)[1]', 'int') as ItemQty,

itemsxml.r.value('(price)[1]', 'money') as ItemPrice

from (

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDateFromXml,

OrderDetailsXml

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

) as orderdata

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order/items/item') itemsxml(r)

) as orderdata

order by OrderDateFromXml desc;

It can become a bit of a hassle, and this is clearly the type of problem that warrants very careful planning and analysis. After running this query, line 7 now shows the correct calculated line total of 30.

Querying the XML

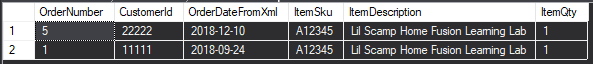

Prior this, we’ve only returned data from the XML document, but the same value function works in the where clause. Let’s say the Lil Scamp Corporation has notified us of a safety recall on their “Home Fusion Learning Lab” product. We need to know who has ordered SKU A12345. It’s as simple as adding this where clause:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

with

parsedorder (OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CustomerId,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

)

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

OrderDateFromXml,

itemsxml.r.value('(sku)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemSku,

itemsxml.r.value('(description)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ItemDescription,

itemsxml.r.value('(quantity)[1]', 'int') as ItemQty

from (

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDateFromXml,

OrderDetailsXml

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

) as orderdata

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order/items/item') itemsxml(r)

where

itemsxml.r.value('(sku)[1]', 'varchar(max)') = 'A12345'

order by OrderDateFromXml desc;

Unfortunately the alias limitation also applies here. Because value is a function, you should give very careful consideration to the data you’re querying. Using a function in a where clause is guaranteed to cause table scans. This could be mitigated with even more CTEs and/or sub-selects. The query shown above tells us just two customers need to be notified of the product recall:

URL-Encoded XML

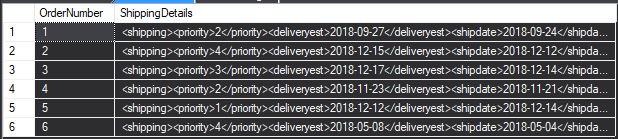

Let’s turn our attention to the second challenge – processing data supplied by an external party as URL-encoded XML. Keep in mind that the results grid in Visual Studio and SQL Studio will decode the URL-encoding which can be misleading and confusing at first. If we just output the <shipping> node directly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

with

parsedorder (OrderNumber, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

)

select

OrderNumber,

orderxml.r.value('(shipping)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as ShippingDetails

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r);

Similar to the raw OrderDetails column itself, it looks like XML but this is actually just text:

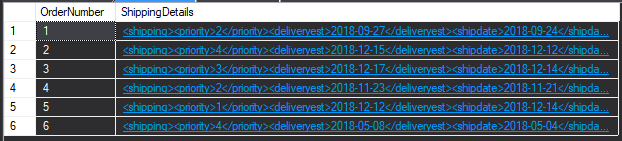

The good news is that the cast function also understands URL-encoded text. Notice how a true XML document is represented in the results grid after cast parses the content:

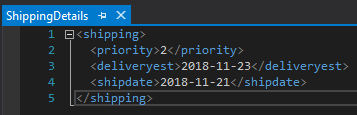

As the underlined blue text suggests, these are links which you can click to view the formatted XML in a separate window:

So what’s the big deal? Why bother with this example? While you could do an inline cast, this would be very inefficient since it would have to be repeated for each use of the value function to extract the child nodes, and the syntax is further complicated by the fact that the value function doesn’t support XML as a conversion target data type:

1

cast(orderxml.r.value('(shipping)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as xml).value('(shipping/deliveryest)[1]', 'date') as DeliveryEstimate

That’s a whole bunch of noise just to extract a single value.

Multiple CTEs

This time, instead of a sub-select, we’ll use a pair of CTEs. The first CTE is the same one we’ve been using except that we’ve changed the name to outerxml. The second CTE references the first one, and it adds a column which is the <shipping> node cast to the XML data type. This second CTE gets the parsedorder name we were using in earlier examples.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

with

outerxml (OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CustomerId,

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

),

parsedorder (OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml, ShippingXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CustomerId, OrderDetailsXml,

cast(o.r.value('(shipping)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as xml) as ShippingXml

from outerxml

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') as o(r)

)

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

orderxml.r.value('(orderdate)[1]', 'date') as OrderDate,

shipping.r.value('(deliveryest)[1]', 'date') as DeliveryEstimate

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

cross apply ShippingXml.nodes('//shipping') shipping(r)

order by OrderDate desc;

You can see that the dependent select only needs to reference the parsedorder CTE, which contains both of the XML documents, and extracting the DeliveryEstimate column is a single relatively simple value function call.

Limiting Result Size

Performance-wise, everything in this article is relatively expensive – CTEs, sub-selects, casting and parsing, and xpath expressions.

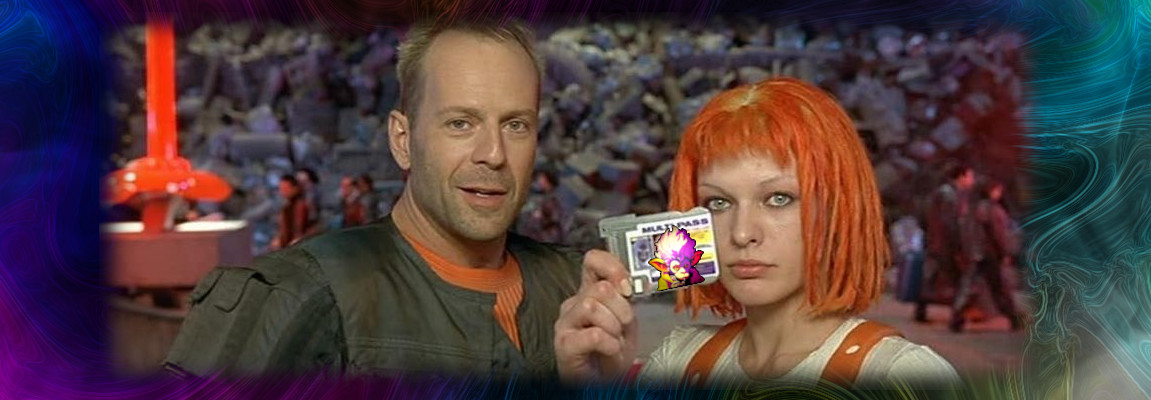

When working with CTEs in particular, limit the amount of data being processed by applying as many restrictions as possible as early in the pipeline as possible. Let’s say our hypothetical company wants to analyze Christmas-season shipping to be sure orders are being delivered according to the customer’s selected delivery speed. In this system, the delivery speed is the shipping/priority value which is the number of days shipping should take. We assume orders are shipped the day after the order is submitted, so the estimated delivery date is “order date + 1 + priority”. We can compare that to “ship date + priority” to determine whether packages are being shipped on time:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

with

outerxml (OrderNumber, OrderDate, OrderDetailsXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, CAST(OrderDate as date),

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

where OrderDate > '2018-11-30'

),

parsedorder (OrderNumber, OrderDate, OrderDetailsXml, ShippingXml)

as (

select OrderNumber, OrderDate, OrderDetailsXml,

cast(o.r.value('(shipping)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as xml) as ShippingXml

from outerxml

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') as o(r)

)

select

OrderNumber,

CustomerId,

OrderDate,

DeliveryEstimate,

DATEADD(day, ShippingPriority, ShipDate) as DeliveryActual

from (

select

OrderNumber,

OrderDate,

orderxml.r.value('(customer)[1]', 'varchar(max)') as CustomerId,

shipping.r.value('(priority)[1]', 'int') as ShippingPriority,

shipping.r.value('(shipdate)[1]', 'date') as ShipDate,

shipping.r.value('(deliveryest)[1]', 'date') as DeliveryEstimate

from

parsedorder

cross apply OrderDetailsXml.nodes('//order') orderxml(r)

cross apply ShippingXml.nodes('//shipping') shipping(r)

) as orderdata

order by OrderDate desc;

This shows us that there was a problem on December 10th – the actual delivery dates are later than the estimated dates:

Obviously this is a very contrived example, but the point is the addition of a where clause in the first CTE:

1

2

3

4

5

6

as (

select OrderNumber, CAST(OrderDate as date),

cast(OrderDetails as xml) as OrderDetailsXml

from OrderHistory

where OrderDate > '2018-11-30'

),

If order volume was consistent throughout the year, this would eliminate 92% of the data in the very first step (at which point a few inadvertent table scans might not even matter).

Another obvious thing to do in this query is to filter the results so that only late deliveries are shown. As usual, the limitation on the use of aliased columns comes into play, and the solution would be the same as with previous examples – use a sub-select. We’ll skip the solution as you should be very familiar with the concept by now.

Conclusion

This isn’t a common problem which can make it difficult and time-consuming to figure out how to address it. As these examples show, the solutions to each aspect are variations on just a couple of themes. Like so many other programming tasks, it’s relatively easy once you know the basic trick.

XML has fallen out of favor over the past few years over more human-readable (and -writeable) formats like JSON and YAML, and I can’t say I enjoy working with XML any more than most, but it’s still a fact of life in the real world. I imagine I’ll refer back to this article as notes to myself, and hopefully it’ll help others facing similar questions with a delivery deadline to meet.

Comments