AI Decision-Making with Utility Scores (Part 1)

An introduction to utility scoring for AI decision-making tasks.

This is part 1 of a series about AI decision-making through the use of a well-known technique called utility scoring. This article will briefly introduce the concept of utility scoring. Although these articles are categorized as “gamedev” and “AI”, the origin of calculated utility values comes from the field of economics, and this approach could easily be applied to almost any decision-making process. Indeed, the library that I will introduce doesn’t have any gaming-specific features whatsoever. Several years ago, my wife and I dabbled in Unity and Xbox programming, and I began writing this library with one of those projects in mind, but the library itself is completely general-purpose. The library is called Active Imagination, and I will update this article once it is available on GitHub and NuGet.

The “utility” associated with an object, an activity or any other thing under consideration is a way to represent the relative importance of that thing in comparison to the alternatives. We use the term “utility” instead of “value” because many things have a fixed, readily identifiable value which isn’t the same as the importance of that thing. A one-hundred dollar bill has a known value, and it probably has a large importance (a high utility score) when shopping in a thrift store, but has little importance (low utility) when shopping at the local Ferrari dealership.

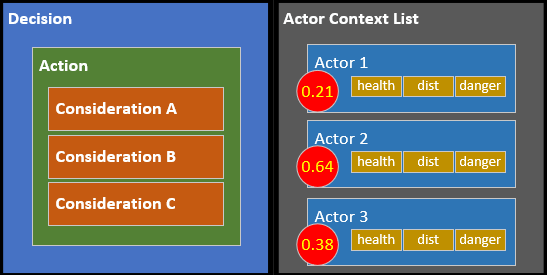

For the purposes of AI decision-making, we can say that an “actor” needs to make a decision between some set of possible actions. The actor needs a way to assign a utility score to each available action so that the actor is able to compare them and select the best option. Each possible action is scored according to a set of considerations, and those considerations are based upon “context” – information about the actor, the goals, the environment, others involved in the game or simulation or activity, and whatever else might contribute to the decision-making process. These are literally all the pieces of the puzzle we need to build a decision-making AI.

Rather than re-hash the how-and-why of utility theory, I recommend dedicating an hour to watching an excellent 2010 Game Developer Conference (GDC) presentation called Improving AI Decision Modeling Through Utility Theory. Even if you aren’t interested in this for game purposes, it’s still an excellent introduction. Dave Mark and Kevin Dill are both well-known developers who have used variations on this concept in many successful game titles, and this presentation is well regarded in game development circles. (I will add a couple of caveats about the presentation: the calculations you’ll see are somewhat simplified and incomplete, and they gloss over some important implementation details in the interests of time and clarity.)

Although it is of less importance to understanding the basic concepts, the same two gentlmenen gave a 2012 GDC presentation called Embracing the Dark Art of Mathematical Modeling in AI. This presentation begins to cover more of the implementation details that were missing from the earlier video, and it approximates much of the architecture you’ll see in my Active Imagination library.

There was also an excellent 2015 GCD presentation (same guys!) called Building a Better Centaur: AI at Massive Scale. The first two thirds are highly relevant to this topic and comes very close to my Active Imagination architecture. Also well worth your time.

Finally, a third set of articles and presentations by Andrew Fray (posted on his blog as Context Behaviours Digest around 2013) discusses a related technique which I prefer to call “Context Steering”, although Andrew seems uncertain about the name he prefers. This is pretty interesting material, too, although it’s a more specialized type of decision-making and using it requires quite a bit more effort. Context Steering is also supported by my Active Imagination library and I’ll save that for a later installment in the series.

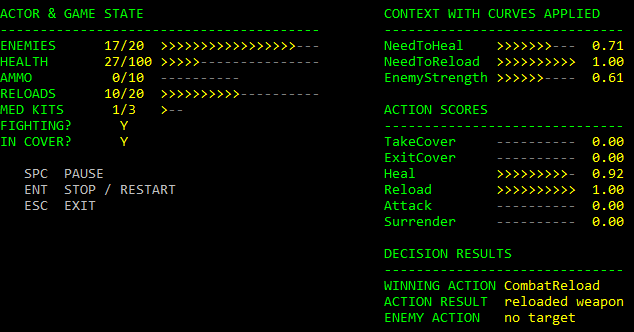

A very important take-away from both GDC presentations is that modeling is a critically important part of this process. The simple demo application I’ll cover in the second installment implements Dave Mark’s example from the 2010 presentation (with a few extra flourishes). Even though I knew what to expect, I admit I was still surprised to see how just a handful of values and possible actions quickly produces interesting and varying behavior. Here’s a quick peek:

The rest of this article and this series assumes you understand the basic concepts from the 2010 GDC presentation, and will be presented within the context of the architecture used by the Active Imagination library.

Elements of a Decision

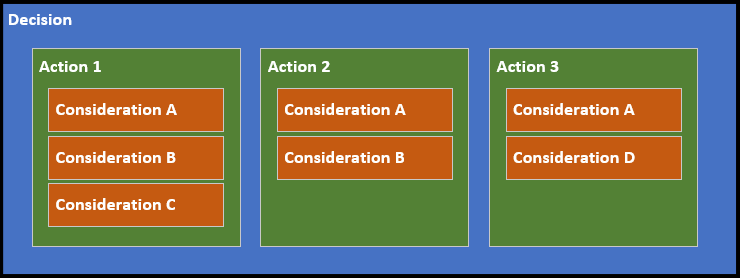

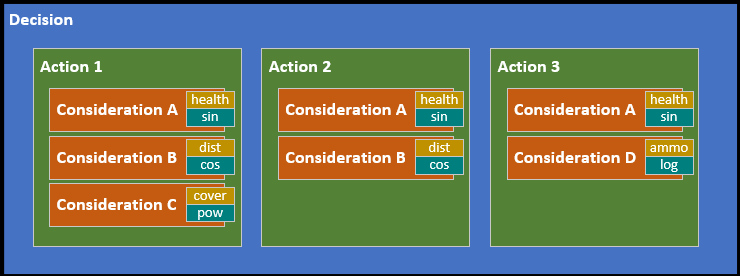

The basic decision model is a hierarchy of information:

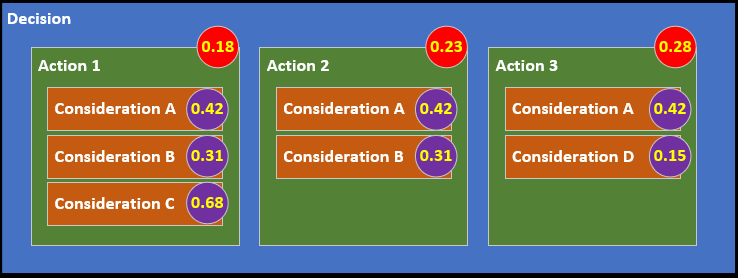

Considerations are scored individually by evaluating one or more Context values. Context is information about the Actor which needs a decision, the environment, or anything else relevant to the Consideration. Within the Active Imagination library, Context data is stored as lists of key-value pairs, so most Considerations relate to a specific Context key along with various properties to control the interpretation of that Context value, such as the curves discussed in the presentation.

Each Action’s Consideration scores are then combined (using an algorithm Dave Marks presents in the 2015 GDC lecture, click the “Compensation Factor” video bookmark) into a single Action score. These can then be compared to determine the best Action for that group of Context values. Context values, Consideration scores, and Action scores are usually stored as a float value normalized to the 0..1 range, which makes it easy to compare and combine them. You can see below that Action 3 has the best score.

A Decision most commonly applies to a whole group of Actors of the same type – race cars, soldiers, employees – they likely share the same selection of Actions with the same Considerations, but the inputs to those Considerations will vary. This is why Active Imagination uses the term Actor Context instead of just Context. While all Context information isn’t necessarily from the Actor in question, Context data influences the Considerations that controls how the Actor makes decisions.

Thus, each Decision in the Active Imagination library also needs something called an Actor Context Factory to generate the raw input values processed by the Considerations. When a Decision needs to be made, the Actor Context Factory generates a list of Actor Context objects, each relating to a specific Actor that will use the Decision. Each Actor Context object contains a list of key-value pairs which are the raw inputs to the Considerations.

Making a decision (by choosing an Action) and actually executing on that decision are two separate steps in Active Imagination. The idea is that all Decisions are processed against the same Context data. Once all of the desired Actions are known, then the Actions can be executed. Because a Decision can be processed for many Actors, the “winning” Action is not stored in the Decision – it is stored with the Actor Context data.

Active Imagination calls this type of decision-making process a ChooseActionDecision and it is the most common approach you’ll see for utility-based AI implementations.

Best Man for the Job

A slightly different processing model is also available with Active Imagination: identifying the best Actor to perform an action, rather than selecting among a list of Actions. In this case, the Decision just one Action, and Consideration scores are combined and stored with each Actor Context. You can see in the following example that the Actor Context data for Actor 2 produced the highest score, identifying that Actor as the best candidate to handle the Action.

Where would this be useful? Consider if the example represents a squad of soldiers, and the Action controls which soldier needs attention from the squad’s medic. A combination of each soldier’s overall health, distance from the medic, and general danger level allows the medic to choose the best candidate for healing.

Active Imagination refers to this as a ChooseActorDecision.

While this same process could be represented by the Action-based Decision processing described earlier, it would require setting up each squad member as an Action, which is a bit awkward and would require a lot of work at runtime. However, by turning the scoring process inside out, the same Actor Context data can serve both types of Decisions.

Scoring Curves

As explained in the 2010 GDC presentation, it’s very useful to apply mathematical functions to the raw input data. Out of the box, Active Imagination provides nine Scoring Curve classes. Six of these have parameters for tweaking the curves, and of course, you’re free to define your own Scoring Curve classes. I have also used the very cool free calculation-graphing website Desmos to provide visualization of the curves and an easy way for you to experiment with the parameters.

Later installments in this article series will go into more detail about using these. Right now we’ll just take a quick look at what is available.

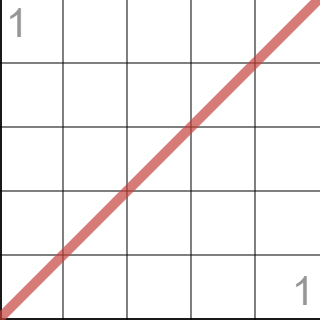

CurveNone

Not much to say about this one – it returns the raw Actor Context input data without modification.

CurveLinear

This class is also pretty basic, but it offers control over Slope and Offset parameters.

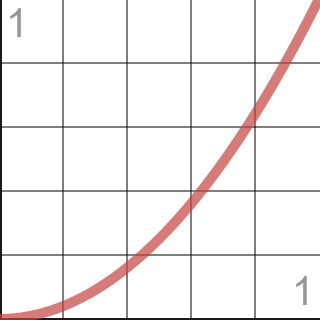

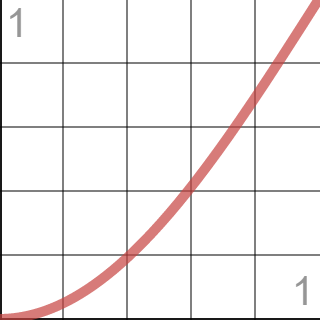

CurveExponential

This class raises the input data to a configurable exponent, producing a very rapid increase in the resulting score. It offers Exponent and Offset parameters.

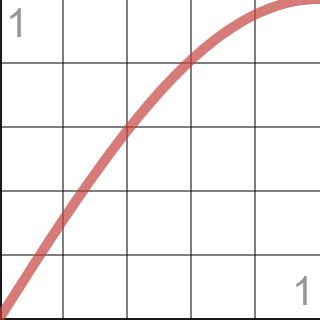

CurveSine

This shape is sometimes referred to as “ease-out” by animators because of the way it makes animations appear to slow down towards the end (when the input is a timeline). It offers Steepness and Offset parameters. This is a good one to play around with in the interactive viewer. Because of the repeating nature of a full sine wave, some combinations of parameters will pull other parts of the shape into the 0..1 normalization range which would create undesirable quirks in scoring behavior.

CurveCosine

The cosine is simply an out-of-phase sine wave. Animators refer to this as “ease-in” because it starts off slowly. This offers the same Steepness and Offset parameters and larger values can create the same kinds of problems described above for sine curves.

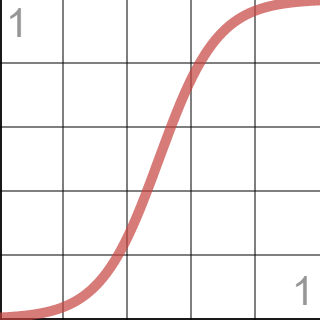

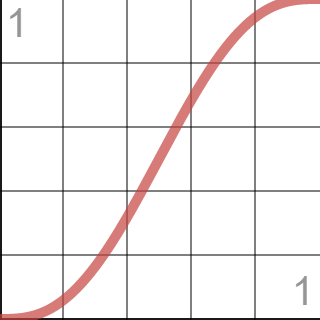

CurveLogistic

The logistic curve is one of Dave Mark’s favorites (it’s in the GDC 2010 video) and it’s especially easy to customize. It offers two parameters, Steepness and Midpoint.

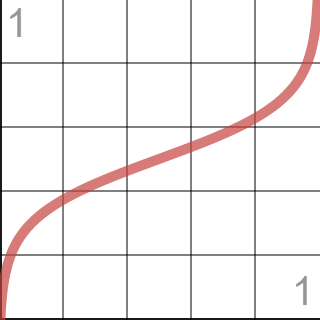

CurveLogit

As Dave remarks in the presentation, a logit curve is a logistic curve turned on its side. It offers one parameter, LogBase, which by default is set to the mathematical constant e (Euler’s number). For the purposes of the interactive version, 2.72 is as close as you’ll get to e (and that is the default when you first land on the page).

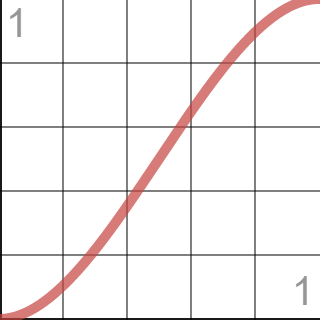

CurveSmoothstep

Smoothstep is a very well-known curve in game development and animation circles. It doesn’t offer any configuration parameters, but of course, you’re free to play with the equation on the Desmos website.

CurveSmootherstep

Smootherstep is another well-known curve that goes a bit beyond smoothstep. It also does not offer any configuration options.

Conclusion

Although the real Active Imagination library is considerably more complex than the Decision and Context diagrams might suggest, these handful of concepts form the core of the whole system.

In the next installment, we’ll use my Active Imagination library to build and test a real decide/act loop in a game-like program based on Dave Mark’s examples in the 2010 GDC presentation.

Comments