How to Close a WebSocket (Correctly)

WebSockets are all about state-management.

Back in January, I posted an article titled A Simple Multi-Client WebSocket Server which demonstrated how to write a WebSocket server with realistic features. That article used a browser-based client, but this month I started working on a new project which happened to require a .NET WebSocket client, and to my dismay, I realized my code to handle closing a WebSocket had problems that were simply ignored by web browser clients. Before I get into the details, there is a bug in .NET Core client WebSocket implementations prior to .NET Core 3.0 which makes it impossible to cleanly close a WebSocket from the client. The code now on GitHub uses 3.0, currently in preview, but it works.

Consequently, the WebSocketExample repository on GitHub for that older article has been heavily overhauled, and it also includes a third project called WebSocketClient which (not surprisingly) is a complete .NET WebSocket client. I’ll discuss that briefly, but the general concept actually is pretty close to the WebSocket server shown earlier, apart from closing the connection.

Update: The code has been updated as a result of a newer article, A Minimal Full-Feature Kestrel WebSocket Server.

Breaking Up is Hard to Do

A 2011 IETF document that goes by the thrilling name RFC 6455 defines the WebSocket protocol. The “Closing Handshake” is briefly described in Section 1.4 and it sounds relatively simple. Either the client or the server sends a Close frame (WebSockets borrow a lot of TCP terminology, so you exchange data in “frames”), and the other side sends back its own Close frame in response, and then both parties can close their connections. Easy, right?

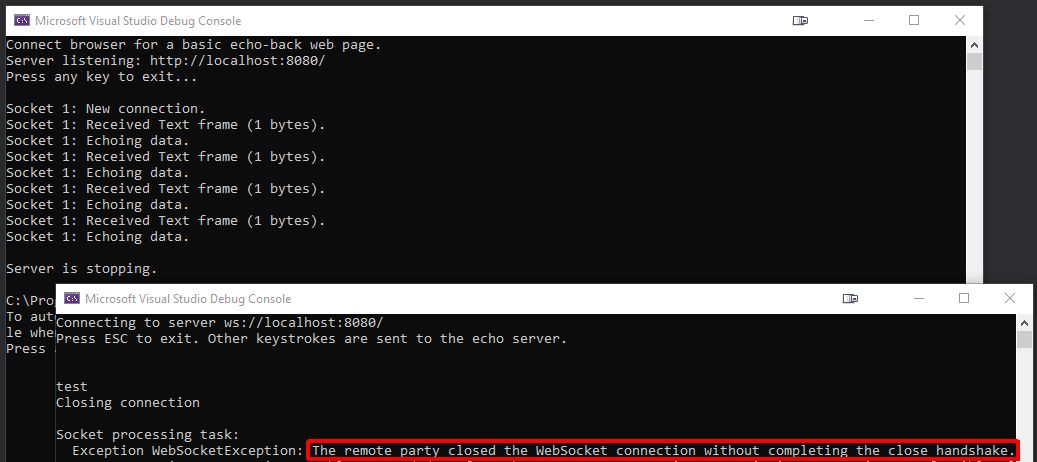

It was pretty easy to get a .NET WebSocket client up and running. It really is mostly a variation on the server code from the earlier article. But every attempt to close the connection, whether I initiated it from the client or the server, resulted in one or both sides throwing an exception with the message The remote party closed the WebSocket connection without completing the close handshake.

In .NET the closing handshake happens through a series of state transitions. Ignoring which is the client and which is the server, a session between Party A and Party B should look like this:

- Both parties are connected and in the

Openstate - “A” sends a Close frame

- “A” switches to the

CloseSentstate - “B” receives the Close frame

- “B” switches to the

CloseReceivedstate - “B” sends an acknowledgement of the Close frame

- “B” switches to the

Closedstate - “A” receives the acknowledgement

- “A” switches to the

Closedstate - Both parties are now disconnected

As mentioned in the introduction, there is a bug in .NET Core prior to 3.0 that wasted about two days of my life. A client WebSocket that starts the closing handshake fails to transition to the Closed state when the server acknowledges the initial Close frame. Instead it reacts as if the server is initiating a closing handshake by going to the CloseReceived state, and is then “surprised” when the server closes the socket. So even though I was pretty sure my code was correct, no matter what I tried, the client threw the dreaded exception The remote party closed the WebSocket connection without completing the close handshake.

There’s a lot of sketchy advice if you search the Internet for that exception message. Many people simply catch and ignore the exception, claiming it’s normal and there’s nothing you can do about it. You should catch it, though – real-world WebSockets are known for closing unexpectedly. The point is that there is a correct way to close your connections.

In the code for my January article, I responded to a Close frame by calling CloseAsync, but that was the wrong thing to do. It turns out that .NET offers two methods related to closing a WebSocket, CloseAsync and CloseOutputAsync, and since I just said I used the wrong one, you’ve probably guessed that CloseOutputAsync is the correct response to a Close frame.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

if (receiveResult.MessageType == WebSocketMessageType.Close)

{

// Bad.

//await socket.CloseAsync(WebSocketCloseStatus.NormalClosure, "", Token);

// Good.

await socket.CloseOutputAsync(WebSocketCloseStatus.NormalClosure, "", Token);

}

else

{

// Read the buffer, do awesome stuff with the data.

}

The real question, though, is how to correctly start the closing handshake process. The .NET Core documentation is terrible for CloseAsync and CloseOutputAsync. There is a really useful comment about how these methods work, but it only appears in the docs for the old .NET Framework AspNetWebSocket class, and it wasn’t clear if the .NET Core implementation works the same way. Based on my testing, I don’t think it does – here is what I learned:

When you’re writing client WebSocket code and the client wants to intiate the shutdown, call CloseOutputAsync. This transitions the socket to the CloseSent state, which appears to be required to transition to the Closed state when the server replies. You should also watch the socket state until it is actually closed.

When you’re writing server WebSocket code and the server wants to initiate the shutdown, call CloseAsync. This handles the entire closing handshake flow correctly.

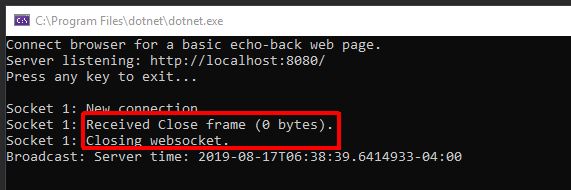

With the correct closing code in place, the server responds cleanly when the client closes the socket, and vice-versa:

ReceiveAsync Hates a Quitter

A very surprising problem I ran into is how ReceiveAsync reacts when you actually cancel the CancellationToken passed into it. In short, it trashes the WebSocket and sets the State to Aborted. In other words, if you cancel ReceiveAsync you can’t ever use that WebSocket again for anything, including trying to close it gracefully. (For anyone who has ever suffered through low-level socket programming against the low-level winsock API, this actually makes sense – but I had hoped the managed implementation was a little more friendly.) All you can do is Dispose it and move on. Also, the party at the other end of the connection will (as usual) throw the exception The remote party closed the WebSocket connection without completing the close handshake. I was really getting tired of that exception.

I wasted a lot of time on that before realizing that’s the intended behavior (apparently Microsoft can’t be bothered to document that, either). It seemed like a pretty clean, obvious workflow to cancel the token for ReceiveAsync before starting the Close process, but in fact you have to just let ReceiveAsync lurk over there in the corner while CloseAsync goes about its business.

You can only safely cancel the ReceiveAsync token after you’ve completed the WebSocket close handshaking process.

Refactoring the Server Example

In the old article, I stored the broadcast messages in a thread-safe collection. After rearranging things for a cleaner shutdown, it became easier to store the WebSocket object itself and the broadcast loop’s CancellationTokenSource in collections of their own. At that point it became clear that the project should just have a separate object describing each client connection, hence the new ConnectedClient class.

In the earlier article I urged the reader to learn more about these thread-safe collections, but there are more “TryXYZ” methods in use now, so I want to emphasize this is not production-ready code, in terms of the use of thread-safe collections. For example, the calls to TryAdd may fail, and for the sake of creating an easy-to-follow example, failure to add to the collection isn’t handled at all. Even in a moderately busy server scenario, you are almost guaranteed to encounter collisions (one thread reading from the collection while another tries to add to it).

It goes without saying that the response to these situations is implementation-dependent. In the real project that led to this article, I typically delay the thread for a couple hundred milliseconds and try again. For serious, complex applications, you may even want to offload the retry behavior to a configurable policy-driven library such as Polly.

HttpListener is Going Away

The WebSocket server in these articles is based upon upgrading an HTTP connection that is established with HttpListener. Unfortuantely, Microsoft has decided to bank on their Kestrel architecture. The HttpListener class will be deprecated, probably sooner rather than later, knowing how Microsoft has been behaving lately. This decision has me very concerned. Kestrel has amazing performance but it feels like .NET is slowly losing it’s general-purpose capabilites in favor of “most-common-use-case” framework bloat.

Editorializing aside, it’s important to note that the .NET Core implementation of HttpListener doesn’t even bother to implement SSL/TLS support (!).

In the next few days, I will investigate how to set up a minimal Kestrel-based WebSocket server. If I’m successful, I’ll post the results.

Conclusion

If anything, these latest discoveries are an even stronger argument against the oversimplified sample code on the Internet. It’s almost impossible to use WebSockets correctly based on examples of that nature. Worse, there is very little information about correct usage even if you’re willing to read the docs. Microsoft is so fixated on frameworks and dumbing down code into “patterns” that all you’ll find is how to set up sockets through SignalR within the heavy-weight context of an ASP.NET Core MVC web application.

Comments