A Simple Multi-Client WebSocket Server

Learn from this simple websocket server with realistic features.

Update: The GitHub code for this article has been updated as a result of my newer August 2019 articles, How to Close a WebSocket (Correctly) and A Minimal Full-Feature Kestrel WebSocket Server.

In the old days, dumping debug information to the console was disparagingly referred to as “printf debugging”. After all, when your only output is the character mode screen (I’m talking the really old days, the 70s and 80s), trashing everything with debug output was kind of sloppy. But regardless of what crusty old C programmers might think, these days I make heavy use of this approach. I recently ran into a scenario where it would be very handy to have multiple consoles. I was very surprised to discover Windows doesn’t support this – not even if you’re willing to p/invoke calls to the Win32 API.

There are lots of other ways to accomplish similar results, of course. If the data is minimal, stash it into a List<string> and dump it to a file. For heavyweight requirements, you could go to extremes and use a plug-in logger like Serilog. But old habits die hard, and I wanted live, console-style output. The next best thing was to send my output to another process, a console-by-proxy.

Back in the 90s I had done interprocess communication using Windows’ named pipes feature. I hadn’t touched them since they were introduced about ten years ago in .NET 3.5, but it seemed like a reasonable place to start since I already had some experience under my belt. Unfortunately, I had forgotten just how clumsy they are. Suffice to say I wasn’t satisfied with the result, which is why this article is about websockets instead of named pipes. The only other thing I’ll say about named pipes is that if you have a burning desire to mess around with them, my NamedPipesExample GitHub repo is probably a good place to start.

If websockets are kind of old news by this point, named pipes are positively ancient. In spite of both being around for quite awhile, I was surprised by the lack of “functional” examples. There is plenty of code out there that works, but the examples never seem to do anything in a realistic fashion. Very infrequently, the opposite problem applies – I want an example, not the source for a full-blown production-quality application. I can write all kinds of code that compiles and runs, but Doing Useful Stuff is the name of the game, and apparently striking that balance when writing sample code is more difficult than it seems.

Before we dig in, I’ll mention that all of the code for this article can be found in my WebSocketExample repository on GitHub.

Realistic Functionality

Probably the best websocket example I found online was from Microsoft’s own Paul Batum. Back in 2011, he blogged about them, accompanied by code that included decent comments in a unique side-by-side presentation. The projects I’ll present are loosely based on his code. And to be clear, I’m not saying his was a “bad” example (in fact this guy liked it so much he appears to have straight-up hijacked the code for his own “article” on the topic). But it suffers from the problem I mentioned above: it works, but it isn’t very clear how to turn it into something useful. And the worst part is that making it useful is pretty easy.

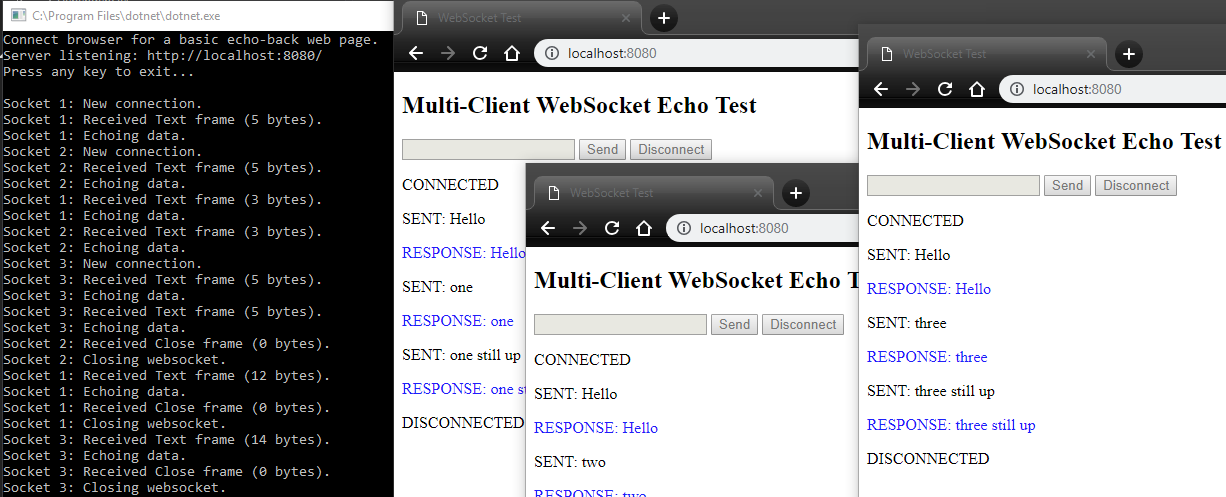

The most common websocket demo is an echo server – anything the server receives is sent back to the same client. Paul’s example worked this way, and so do the two examples I present here. That in itself isn’t particularly useful except that it covers send and receive at both ends of the pipe. But every example I found had the same major limitation: the server could only handle a single client (some examples couldn’t even do that much – the server could only handle a single receive/echo cycle).

With a small handful of additional code and some Task management, it’s easy to create an echo server that can handle a very large number of simultaneous clients. But even that isn’t realistic because, as you’ll see, once a websocket connection is established, the “servicing loop” is isolated into its own separate Task. A real program does more than simple echo operations, which implies communications to and from the world outside of a Task loop. Thus, the GitHub repository contains two sample projects – WebSocketExample, which is your basic multi-client echo server, and WebSocketWithBroadcast, which is an echo server, but the outer Main loop also periodically broadcasts the server time to all connected websocket clients.

These two projects differ from every other example I’ve found in a couple of interesting ways.

In terms of the problem I was originally trying to solve, I quickly realized that once I had a websocket server running, a simple HTML+JS client might be superior to a dedicated console-based websocket client app. JS has done a good job at making websockets ridiculously easy to use, and since the initial connection of a websocket is HTTP-based (a process called “upgrading” the HTTP connection to a separate new websocket connection), that also meant my demo servers could deliver this basic HTML+JS client app. They are effectively the server and client wrapped into one. Of course, nothing prevents you from writing a stand-alone websocket client app if your data-exchange needs are more complex than “dump to console” streaming.

The other big difference is the basic design of the control-flow in my code. None of the examples I found were able to cleanly handle the shutdown process. The HTTP side of the system is based upon the HttpListener class, which includes a Start and Stop method, yet none of the examples allowed for a clean use of Stop. This, too, is easy to accomodate with relatively minor adjustments in the overall application structure.

And of course, since I’m using .NET’s modern async Task features (which were still rather primitive under .NET 4.0 when Paul published his example), we want full cancellation support to maximize our control over the process – again, something that only takes a few extra lines of code to realize.

Echo Echo Echo

We’ll start with the basic echo server shown in the WebSocketExample project. As mentioned above, if you run this server, you can point as many browser instances at http://localhost:8080/ as you want and they’ll all establish their own separate websocket channels back to the echo server. The project serves up a simple HTML+JS page with a text input box and buttons for Send and Disconnect. This web page is hardcoded as a string constant for the sake of simplicity.

The Main loop is surprisingly simple – a call to the server’s Start method, watching for a keystroke to end the program, and a call to the Stop method. In a real application, of course, you’d probably have some additional configuration-reading code here, plus setting up all the actually-useful stuff your program needs websocket communications for in the first place. But the websockets themselves are really this simple in terms of managing them “from the outside.”

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

static void Main(string[] args)

{

try

{

WebSocketServer.Start("http://localhost:8080/");

Console.WriteLine("Press any key to exit...\n");

Console.ReadKey(true);

WebSocketServer.Stop();

}

catch(OperationCanceledException)

{

// this is normal when tasks are canceled, ignore it

}

Console.WriteLine("Program ending. Press any key...");

Console.ReadKey(true);

}

We also capture an OperationCanceledException which is the more general form of the Task-specific TaskCanceledException, which is commonly thrown by asynchronous operations which can be canceled. The “cancellation token” structure is a thread-safe way to signal to an async process that it should wind down whatever it’s doing and exit. This is typically done by periodically looping while checking the IsCancellationRequested property of the token passed into the async method, but since it can get ugly to pepper your code with many nested if-checks against this, the token also includes a method called ThrowIfCancellationRequested, which does exactly what the name suggests – ends the Task immediately by throwing an exception. You’ll see this empty catch in several places in these examples.

The interesting code is in the WebSocketServer class. I don’t much care for static classes and methods, but for this simple example, I didn’t see any overwhelming reason to add a few extra lines of code to support instancing. Applications only need a single HttpListener so that also argues for a static approach (you can’t bind multiple instances of that class to the same URI).

Just four methods are needed for a complete, correct echo server: Start and Stop, which are self-explanatory, Listen which implements the HTTP portion of the process, and ProcessWebSocket which loops for each new websocket client for as long as the connection remains open.

We also use a few static fields. The single instance of HttpListener is used by Start and Stop and Listen, and the CancellationTokenSource as well as the CancellationToken itself are stored at the class level, which allows any of the methods to both watch for cancellation or request cancellation. Finally, we have an integer named SocketCounter, which is incremented whenever a new connection is established. This acts as a unique ID for the websocket processing loop. In theory we’d want to somehow throttle the number of active connections, but for the sake of a demonstration this isn’t important. (ASP.NET 4.5 was documented as supporting more than 100,000 concurrent websocket connections, and this example is certainly more lightweight than that stack!)

The Start method accepts a URI Prefix (refer to the documentation for more information about how these are formatted, warnings about secure usage, and so on). Notice we wrap up the Listen method call in a separate async Task but we don’t store the Task handle, and we definitely don’t want to await it because it loops indefinitely. The Listener.IsListening check is probably unnecessary since most startup issues seem to throw an exception.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public static void Start(string uriPrefix)

{

TokenSource = new CancellationTokenSource();

Token = TokenSource.Token;

Listener = new HttpListener();

Listener.Prefixes.Add(uriPrefix);

Listener.Start();

if (Listener.IsListening)

{

Console.WriteLine("Connect browser for a basic echo-back web page.");

Console.WriteLine($"Server listening: {uriPrefix}");

// listen on a separate thread so that Listener.Stop can interrupt GetContextAsync

Task.Run(() => Listen().ConfigureAwait(false));

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("Server failed to start.");

}

}

The Stop method is even simpler, but this is a piece of the puzzle that the other examples are missing – how to cleanly terminate the HttpListener once it has started listening. We’ll discuss that more momentarily, but here you can also see we’re invoking the Cancel method on the cancellation token, then disposing the token source. (Stephen Cleary, the .NET world’s Grand Master of Threading, has pointed out that Dispose doesn’t do much and probably isn’t necessary as long as the token source WaitHandle isn’t used – and it’s almost never used – but I figure it can’t do any harm, either.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public static void Stop()

{

if(Listener?.IsListening ?? false)

{

TokenSource.Cancel();

Console.WriteLine("\nServer is stopping.");

Listener.Stop();

Listener.Close();

TokenSource.Dispose();

}

}

Update: See my newer followup article How to Close a WebSocket (Correctly) for an explanation about problems with this Stop() method.

Your HTTP Qualifies for an Upgrade

Now we get to the good stuff: the Listen method is where we process the HTTP portion of the pipeline. The Start method executes Listen as a separate async Task, and at first glance, the code is controlled by the usual token-testing loop:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

private static async Task Listen()

{

while (!Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

HttpListenerContext context = await Listener.GetContextAsync();

// TODO: request-processing

}

}

However, unlike most async methods, HttpListener.GetContextAsync doesn’t accept a cancellation token. I haven’t been able to find an explanation for this, but the key to terminating the listener is the HttpListener.Stop method. This is what I meant earlier about needing a different application structure than you’ll find in the other websocket examples on the Internet: they don’t allow for clean termination, they just let the app end, apparently assuming that the .NET process teardown will do the right thing. I have no idea if it does, but anyone with raw socket programming experience will tell you it’s easier to mess up socket management than it is to get it right. And, of course, it isn’t even difficult to do it the right way, as you can see here.

When a request arrives, the HttpListenerContext object provides access to all the important details such as the HTTP headers. It’s capable of recognizing when a request wants to “upgrade” the HTTP connection to a new websocket connection, and this is exposed via the IsWebSocketReqest property.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

private static async Task Listen()

{

while (!Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

HttpListenerContext context = await Listener.GetContextAsync();

if (context.Request.IsWebSocketRequest)

{

// TODO: set up a websocket and related communications

}

else

{

// TODO: regular HTTP activites go here

}

}

}

We’ll start by looking at the regular HTTP portion of this method, since that’s how our browser-based demo client initially connects to the server. Most examples simply respond to a non-websocket request with an HTTP error. However, it’s trivial to recognize a request that accepts an HTML page and to serve up something useful. The HttpListenerContext object will look very familiar to anyone who has worked with ASP.NET HTTP context data. It’s a simple matter of converting our HTML to a byte array, setting a few response headers such as the HTTP status code, and streaming the results back to the client. (It’s very important to call Response.Close, or the client will wait forever for the end of the transmission.) In this case HTML is a literal-string constant stored in the class itself, but obviously a real application would probably send a file (or perhaps even multiple files). In the event that the request doesn’t support HTML, we respond with an HTTP 400 Bad Request error.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

private static async Task Listen()

{

while (!Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

HttpListenerContext context = await Listener.GetContextAsync();

if (context.Request.IsWebSocketRequest)

{

// TODO: set up a websocket and related communications

}

else

{

if(context.Request.AcceptTypes.Contains("text/html"))

{

ReadOnlyMemory<byte> HtmlPage = new ReadOnlyMemory<byte>(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(HTML));

context.Response.ContentType = "text/html; charset=utf-8";

context.Response.StatusCode = 200;

context.Response.StatusDescription = "OK";

context.Response.ContentLength64 = HtmlPage.Length;

await context.Response.OutputStream.WriteAsync(HtmlPage, Token);

await context.Response.OutputStream.FlushAsync(Token);

}

else

{

context.Response.StatusCode = 400;

}

context.Response.Close();

}

}

}

Finally, we add the code to upgrade the connection to a websocket and kick off the processing loop. The AcceptWebSocketAsync method is another case where a cancellation token is not used. I haven’t found any evidence that this is a common source of trouble, although I did find one discussion that engaged in some very complex threading gymnastics just to make this one call cancellable (and I haven’t linked to it because I’m not convinced they managed to achieve their goal). Suffice to say it’s a simple and fairly low-level operation that isn’t likely to hang long enough to require cancellation, although a real app should have better exception handling here. Here is the snippet that completes the if block shown above, followed by a detailed discussion:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

HttpListenerWebSocketContext wsContext = null;

try

{

wsContext = await context.AcceptWebSocketAsync(subProtocol: null);

int socketId = Interlocked.Increment(ref SocketCounter);

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: New connection.");

_ = Task.Run(() => ProcessWebSocket(wsContext, socketId).ConfigureAwait(false));

}

catch (Exception)

{

// server error if upgrade from HTTP to WebSocket fails

context.Response.StatusCode = 500;

context.Response.Close();

return;

}

AcceptWebSocketAsync returns a different type of websocket-specific context. Notice the subProtocol: null argument. A sub-protocol is an application-specific feature meant to control how the client and server will communicate once the websocket is established. (It is a “sub” protocol because websockets is the “real” protocol.) The client can list the sub-protocols it supports, and this parameter notifies the client of the protocol chosen by the server. Examples might be “text” or “json”, although it appears sub-protocols aren’t a widely-used feature.

We also use the thread-safe Interlocked class to increment the websocket counter, and the result is the unique ID of the new websocket we’re about to create. In this particular example the ID is only used for output purposes, but in the other WebSocketWithBroadcasts example we’ll talk about shortly, it plays a more important role.

Finally, the websocket context data and the socket ID are handed off to the websocket processing loop in the ProcessWebSocket method. This is wrapped in an asynchronous task. (The leading underscore-assingment syntax is a discard added in the 7.0 version of the C# language – it just means we don’t care about the return value, but since we do have an assignment, Roslyn won’t complain that we haven’t awaited or stored the Task).

WebSocket Processing Loop

At this point we’re ready to actually work with a websocket connection. This code sets up a 4K buffer then loops as long as the websocket is open and the cancellation token hasn’t been cancelled. Unlike the HTTP-oriented methods, the websocket methods do accept a cancellation token. After the code, we’ll discuss a few aspects and features about working with websockets.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

private static async Task ProcessWebSocket(HttpListenerWebSocketContext context, int socketId)

{

var socket = context.WebSocket;

try

{

byte[] buffer = new byte[4096];

while (socket.State == WebSocketState.Open && !Token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

WebSocketReceiveResult receiveResult = await socket.ReceiveAsync(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer), Token);

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Received {receiveResult.MessageType} frame ({receiveResult.Count} bytes).");

if (receiveResult.MessageType == WebSocketMessageType.Close)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Closing websocket.");

await socket.CloseAsync(WebSocketCloseStatus.NormalClosure, "", Token);

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Echoing data.");

await socket.SendAsync(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer, 0, receiveResult.Count), receiveResult.MessageType, receiveResult.EndOfMessage, Token);

}

}

}

catch (OperationCanceledException)

{

// normal upon task/token cancellation, disregard

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine($"\nSocket {socketId}: Exception {ex.GetType().Name}: {ex.Message}");

if (ex.InnerException != null) Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Inner Exception {ex.InnerException.GetType().Name}: {ex.InnerException.Message}");

}

finally

{

socket?.Dispose();

}

}

Websockets exchange data in chunks called “frames” (a side-effect of being very closely related to the same concept in raw TCP/IP sockets). This example creates a 4K buffer, so if the incoming data exceeds 4K, another chunk will follow until the entire message is completed. Obviously for a simple echo server this isn’t too likely to be a problem, but depending on your real-world scenario, you should keep this possibility in mind. You can’t tell how much data is in a message until the sender sends the end-of-message flag with the last frame (“sender” can be the server or the client). Some usage scenarios such as streaming video many never send an end-of-message frame.

There are three WebSocketMesageType values possible: Text, Binary, and Close. The Close message isn’t really a request, it’s an indicator that the websocket is closing. Normally you want to respond with another close operation on your side which, if nothing else, should release resources. In the case of this server code, it will also change the State to one of the closing values, which will terminate the while loop and complete the Task.

Update: See my newer followup article How to Close a WebSocket (Correctly) for a more in-depth look at how the close handshake is supposed to work.

This example processes Text payloads, although Binary is possible. For some clients the difference may not be important, but in the case of a JS client, a Text message results in a simple string value, whereas a Binary message produces a JavaScript Blob object. Since the echo server can just turn around and send the exact same buffer back to the client, we won’t address outbound buffer setup until we get to the broadcast example.

Notice that the websocket object is disposed by a finally block. Although they’re lightweight, websockets do involve unmanaged resources.

And we’re done! From a purely foundational standpoint of “doing it correctly”, that is all you need to know to work with websockets in .NET. If you want to write a client websocket application, there is a ClientWebSocket class available which basically wraps up a lot of this same functionality. It’s pretty easy to use and you should be able to apply the same async Task techniques to keep your application responsive.

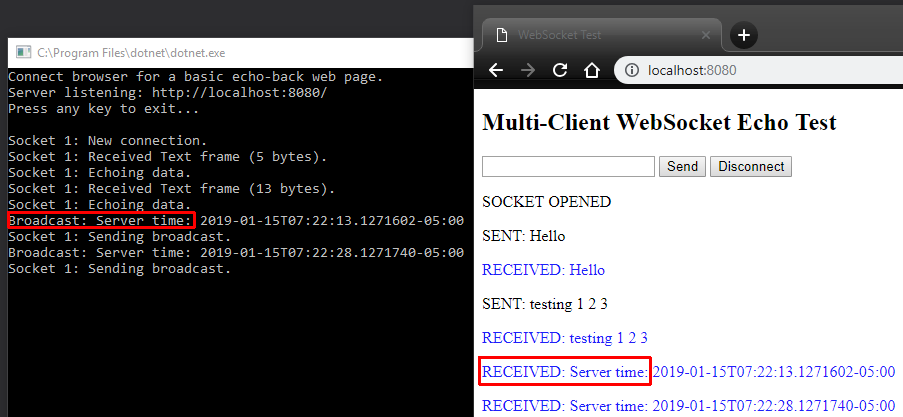

Beyond Echo

My other example is called WebSocketWithBroadcasts. It is the same echo server with one key difference – the Main program loop periodically broadcasts a message (in this case, a server timestamp) to all connected websocket clients. Strictly speaking, this isn’t a websocket problem, it’s more about communication across Task boundaries. However, it exposes a few important considerations you’ll need to accomodate to build a real websocket server.

In the earlier example, we saw that the ProcessWebSocket method is it’s own little world, looping and echoing until the websocket is closed. It isn’t easy to see how to communicate into or out of that walled garden. For this example, the Main “outer” program gets a little more interesting. We start and stop the server in the same fashion, but instead of blocking indefinitely waiting for a keystroke, we’ve added a simple loop which calls a new WebSocketServer.Broadcast message every few seconds.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

const int BROADCAST_INTERVAL_SEC = 15;

static void Main(string[] args)

{

try

{

WebSocketServer.Start("http://localhost:8080/");

Console.WriteLine("Press any key to exit...\n");

DateTimeOffset nextMessage = DateTimeOffset.Now.AddSeconds(BROADCAST_INTERVAL_SEC);

while(!Console.KeyAvailable)

{

if(DateTimeOffset.Now > nextMessage)

{

nextMessage = DateTimeOffset.Now.AddSeconds(BROADCAST_INTERVAL_SEC);

WebSocketServer.Broadcast($"Server time: {DateTimeOffset.Now.ToString("o")}");

}

}

WebSocketServer.Stop();

}

catch (OperationCanceledException)

{

// normal upon task/token cancellation, disregard

}

Console.WriteLine("Program ending. Press any key...");

Console.ReadKey(true);

}

Inside the WebSocketServer class, the Start, Stop and HTTP-oriented Listen methods are identical to those shown previously for the basic echo server. However, we find a new using System.Collections.Concurrent statement at the beginning, and a new static field has been defined:

1

2

3

4

// The dictionary key corresponds to active socket IDs, and the BlockingCollection wraps

// the default ConcurrentQueue to store broadcast messages for each active socket.

private static ConcurrentDictionary<int, BlockingCollection<string>> BroadcastQueues =

new ConcurrentDictionary<int, BlockingCollection<string>>();

The intricacies of these classes are beyond the scope of this article (you can learn more here), but suffice to say that ConcurrentDictionary<T> is a thread-safe dictionary that works much like the normal Dictionary<T>, and BlockingCollection<T> is a thread-safe wrapper around a FIFO queue collection. So, we’re creating a thread-safe dictionary keyed on an integer whose values are a string-based queue. As the comment explains, the key is a websocket ID, and the queued strings are broadcast messages.

The thread-safe classes ensure the Main loop can safely add values to the message queues and the websocket processing loops can safely read values out of those same queues even though the two loops are not directly synchronizing their access requirements with one another. The process of adding a new broadcast message is very simple. Since the dictionary is keyed on the websocket ID integer, the new Broadcast method just loops through all of the active websockets and enqueues the same message over and over again.

1

2

3

4

5

6

public static void Broadcast(string message)

{

Console.WriteLine($"Broadcast: {message}");

foreach(var kvp in BroadcastQueues)

kvp.Value.Add(message);

}

We address this messaging using websocket-specific queues rather than a single message field visible to everyone because it isn’t reasonably possible to determine when any given websocket Task will be available to process a new message. But how does the websocket processing loop read messages from the queue? After all, we saw in the previous example that we must await ReceiveAsync to handle inbound websocket traffic:

1

var receiveResult = await socket.ReceiveAsync(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer), Token);

If we’re waiting for data from the client, how do we arbitrarily send something out over that same connection? My first attempt to solve this was to stop using the shared Token and create a local cancellation token source that self-canceled after a short interval (one of the CancellationTokenSource constructors accepts a millisecond argument). That doesn’t work because cancelling the token causes the websocket to automatically close itself. Worse, the only way the enclosing ProcessWebSocket method could respond to this timeout was to catch the OperationCanceledException – not a great place to add a bunch of code to check the message queue and send whatever it may find.

The correct answer, of course, is to monitor the message queue using another Task. As soon as ProcessWebSocket obtains the websocket reference from context, it executes three new lines of code to set up the queue-processing loop. This creates a new queue in the dictionary keyed to this websocket’s unique ID, it creates a new cancellation token so that ProcessWebSocket can terminate the new Task, then kicks off the WatchForBroadcasts method as a separate async operation. The finally block cancels the child task’s token and tries to remove the websocket’s queue from the dictionary.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// New code added to the ProcessWebSocket startup:

BroadcastQueues.TryAdd(socketId, new BlockingCollection<string>());

var broadcastTokenSource = new CancellationTokenSource();

_ = Task.Run(() => WatchForBroadcasts(socketId, socket, broadcastTokenSource.Token));

// Then later in the finally block:

broadcastTokenSource?.Cancel();

broadcastTokenSource?.Dispose();

BroadcastQueues?.TryRemove(socketId, out _);

At this point we can move on to the new WatchForBroadcasts method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

private const int BROADCAST_WAKEUP_INTERVAL = 250; // milliseconds

private static async Task WatchForBroadcasts(int socketId, WebSocket socket, CancellationToken socketToken)

{

while (!token.IsCancellationRequested)

{

try

{

await Task.Delay(BROADCAST_WAKEUP_INTERVAL, socketToken);

if (!socketToken.IsCancellationRequested && BroadcastQueues[socketId].TryTake(out var message))

{

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Sending from queue.");

var msgbuf = new ArraySegment<byte>(Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes(message));

await socket.SendAsync(msgbuf, WebSocketMessageType.Text, endOfMessage: true, socketToken);

}

}

catch(OperationCanceledException)

{

// normal upon task/token cancellation, disregard

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

Console.WriteLine($"\nSocket {socketId} broadcast task:\n Exception {ex.GetType().Name}: {ex.Message}");

if (ex.InnerException != null) Console.WriteLine($" Inner Exception {ex.InnerException.GetType().Name}: {ex.InnerException.Message}");

}

}

}

This is a pretty simple loop to understand. It watches for the token to be canceled (remember this is the token created and controlled by the ProcessWebSocket parent task, hence the variable name socketToken as a reminder that the class-level Token isn’t used here), and on each pass it delays for awhile, then tries to grab a new message from the queue owned by this web socket. The Delay gives the Main loop a chance to update the queue with a new broadcast message. Without it, repeatedly hammering the TryTake method with new requests would probably keep the queue so busy that the Broadcast method’s Add calls would fail.

If a message was successfully obtained from the queue, we use the typical Encoding.UTF8.GetBytes call to convert a byte array to an ArraySegment<byte> object required by the websocket SendAsync message and send it to the client. And that’s all it takes!

WebSocket Thread Safety

There are still a couple of hidden gotchas in our second example. Rather surprisingly (and probably in the interests of maximizing performance), websockets aren’t thread-safe. The documentation states that it’s safe to have concurrent ReceiveAsync and SendAsync operations in progress, but only one of each. Two concurent SendAsync calls to the same websocket will (apparently) cause trouble.

Fortunately, we have already built the solution to this problem with our dictionary of queues. The earlier echo server simply called SendAsync with whatever was just received, but our Broadcast demo converts that buffer to a string and adds it back to the websocket’s own queue, allowing the queue-processing loop to send it back to the client. The old echo code from ProcessWebSocket looked like this:

1

2

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Echoing data.");

await socket.SendAsync(new ArraySegment<byte>(buffer, 0, receiveResult.Count), receiveResult.MessageType, receiveResult.EndOfMessage, Token);

In the Broadcast version of the server it becomes this:

1

2

3

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Echoing data to queue.");

string message = Encoding.UTF8.GetString(buffer, 0, receiveResult.Count);

BroadcastQueues[socketId].Add(message);

But wait, there’s more! It turns out that closing a websocket is a special-case usage of SendAsync, and that’s what the other part of that same if/else block does in our ProcessWebSocket method. The old code looked like this:

1

2

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Closing websocket.");

await socket.CloseAsync(WebSocketCloseStatus.NormalClosure, "", Token);

Our threading-friendly version needs just two additional statements. One cancels the token which controls the queue-processing Task, and the other removes the websocket’s queue from the dictionary. Then we’re safe to proceed with the normal CloseAsync call.

1

2

3

4

Console.WriteLine($"Socket {socketId}: Closing websocket.");

broadcastTokenSource.Cancel();

BroadcastQueues.TryRemove(socketId, out _);

await socket.CloseAsync(WebSocketCloseStatus.NormalClosure, "", Token);

Exercises for the Reader

Once you start working on a real websockets application, there are a couple of other things you’ll want to keep in mind.

Catching WebSocketException

These examples are missing one exception handler that you should definitely implement: WebSocketException. This will be thrown whenever there is a network-level error (which seems like an unnecessary distraction for the purposes of sample code). In particular you’ll want to inspect the WebSocketErrorCode property, which returns a WebSocketError enumeration describing what went wrong.

Web Socket Security

Just like HTTP web servers, a websocket server must be secured. This is a broad topic which is well-documented on the Internet, so there isn’t any point in re-hashing it here. By way of guidance, you should plan to run over WSS (the protocol name for a websocket using SSL/TLS encryption), and you should also research cross-site vulnerabilities – websockets do not adhere to the Same-Origin policies used by browsers (although the headers are present if you want to add your own CORS whitelisting check). Sadly, it’s a little difficult to find information that doesn’t also assume you’re running under ASP.NET. I don’t have any handy links to share because my current requirements are 100% local-network-based, so I don’t really have a need, though I have read enough about it to know non-ASP.NET information is available if you dig for it.

Concurrent Collection Usage

As stated earlier, the details of using classes like ConcurrentDictionary<T> aren’t really the point of this article, but there are a couple of things you should be aware of (and you should research the proper use of these classes before trying to use them in a real project).

For example, the Broadcast method does a completely normal-looking foreach loop over the websocket queues, but what happens if a request arrives and a new websocket is created during that loop? The answer is that the new websocket won’t get that message: the foreach loop iterates over a snapshot of the dictionary at the time the loop was started.

In general, you’ll want to consider how to handle collisions and timeouts when your code needs to read from or change the contents of these collections. The BlockingCollection<T> class in particular has some interesting timing-based features available.

Doing Useful Stuff

Broadcasting the same message to every connected client isn’t terribly useful, but it makes for an easy-to-understand demonstration. The fact that each websocket has a unique ID means that the server could communicate with individual clients in different ways, depending on the needs of your app. Moreover, this exact same pattern works in the opposite direction: data received from a websocket client can be dispatched for handling elsewhere in the server through the use of thread-safe collections.

Even though websockets turn out to be easy to use, this is still a relatively low-level approach to communication. A fair amount of planning is required to ensure your server and clients share a common data-exchange syntax. Also keep in mind that websockets are relatively cheap in terms of resources. An idle socket uses almost no resources at all. Instead of messing around with complicated data schemes, consider just opening multiple websockets, each dedicated to a different task (the use of sub-protocols would probably come into play here).

Conclusion

This excursion into websockets began with a search for multi-console solution. I wound up with multiple browser windows, instead. The end result is more flexible and scalable than anything I originally had in mind. Sometimes it pays off to follow where the technology leads you.

These examples should help anyone understand how to build a production-quality websocket server. The projects are the sample code I wish someone had written when I started working with websockets a few days ago: clear, simple code that works in a realistic way and that can be readily adapted to useful functionality. Just five or six methods with around 200 lines of code gets the job done!

Comments