Sending Commands to a Running Service

Passing switches and arguments to background Windows or Linux services.

Over the past couple of years, I’ve worked on several projects which are intended to run headless. These have been web applications or APIs, Windows Services, and Linux systemd services. One of those projects (a Raspberry Pi security camera service) accepts a large range of command-line switches and arguments, and I wanted a way to send new settings to the running service without stopping and restarting it. I had hacked together a mostly-working system for this, but later I realized this is pretty generally useful. It deserved to be ported to a stand-alone, reusable library.

The basic idea is that you run the application, and if no other instance is already running, the app sets itself up as a service of some kind. If you run the application while another instance is already running as a service, the new command-line is handed off to the running instance and the new instance exits, optionally receiving a string response from the running instance.

Since this involves two instances of the same application, in the article I’ll consistently refer to the “running instance” (the background service) and the “new instance” (the temporary run which will send new arguments to the running instance).

The source for this library can be found in my Github CommandLineSwitchPipe and v1 of the package is available from NuGet. It targets .NET Core 3.1 since that is a Long Term Service release, and I hope to use this library (and another project I’m working on next) at work where interim releases like .NET 5 are not supported.

Usage Pattern

I want to emphasize this is solely concerned with communicating a command-line to a running instance, and receiving a single string in response. It’s still your responsibility to figure out how to parse the command-line, how to apply changes to your running program, and so on.

Communication is accomplished using a named pipe. I don’t much like working with named pipes, they’re fragile and clumsy, but they’re very lightweight and low-ceremony, unlike a more robust communications system like Web Sockets. (In fact, in one of my projects, I’m using this library alongside Web Sockets.)

The implementation is a static class because it’s meant to be used from a console program’s Main which is itself a static class. The static class is named CommandLineSwitchServer. The implementation involves just two methods, TrySendArgs which attempts to connect to a running instance, and StartServer which is used when a background service starts running.

As the repository’s README explains, as soon as the program starts, call TrySendArgs to send the command-line to any already-running instance. This method returns a boolean which indicates whether another instance of the same program is already running.

If the method returns true because it connected to a running instance, the new instance can read the static QueryResponse property to find out what the running instance sent in response, if anything. (This will never be null, so it can safely be logged or output to the console without checking.) After that, most likely the new instance should simply exit.

On the other hand, if the method returns false because there is no running instance, most likely the new instance should continue with normal startup procedures to assume the role of a running instance. It should create a CancellationToken then invoke StartServer like this:

1

2

3

ctsSwitchPipe = new CancellationTokenSource();

_ = Task.Run(() => CommandLineSwitchServer

.StartServer(ProcessSwitches, ctsSwitchPipe.Token));

It should then process any command-line arguments the program was started with, then begin doing whatever work the program would normally perform.

When the application is going to exit, it should cancel the token provided to StartServer to ensure the named pipe server is closed. (Technically this may not be necessary, but it’s easy to do, and better safe than sorry.)

Switch Handler Delegate

Your application must provide a Func<string[], string> method as the switch-handling delegate. This is the ProcessSwitches argument in the StartServer call shown in the previous section. That means the method accepts a string array and returns a string.

Obviously, the return string is what gets stored into the QueryResponse property on the client (new instance) side of the pipe. My original implementation was one-way, only passing the new command-line, but sending a response was relatively trivial, and not only does this give you a chance to validate the changes were applied, it also allows you to query various bits of data from a running instance, which is incredibly handy.

In the programs I’ve written, there are some switches which are only useful for the original startup process, and other switches which are only useful when passed to a running instance. The demo program shows how I handle this with an overload of the delegate that includes a flag:

1

2

3

4

5

public static string ProcessSwitches(string[] args)

=> ProcessSwitches(args, argsReceivedFromPipe: true);

private static string ProcessSwitches(string[] args, bool argsReceivedFromPipe)

{ ... }

This way, the original instance that will become the running service can invoke the “real” method with argsReceivedFromPipe as false, instructing that method to handle any first-start arguments. Plenty of other patterns are possible and equally valid, of course.

The actual process of parsing command lines can be surprisingly complicated. So far, I have always taken a “roll your own” approach, but there are quite a few libraries out there on NuGet which try to simplify this task. I haven’t used any of them yet, but it’s on my to-do list to review some of the more popular options. If you have experience with any of these, I’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments.

The Demo

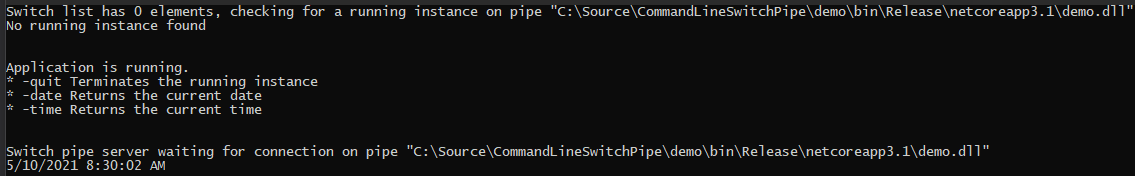

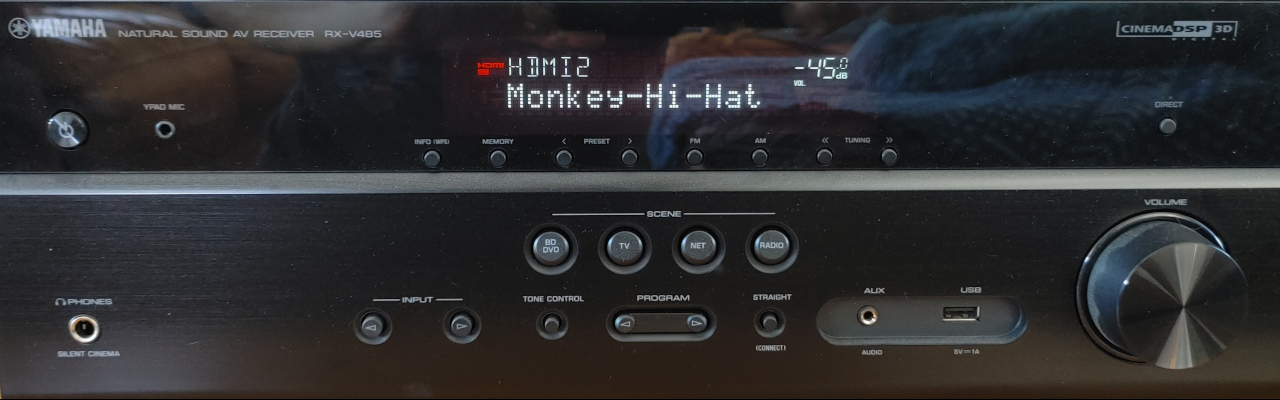

The repository contains a simple demo program. Open two console windows and navigate to the directory with the executable. There aren’t any command-line arguments for starting the running instance, so just run the demo program in one of the windows. The demo is configured to output messages to the console (you’d probably leave this extra noise turned off in a real application). It indicates the named pipe server is listening, then just to keep things interesting and prove it hasn’t died, it shows the current date/time while it waits:

You can see the three switches which can be passed to the running instance. In the second console window, run the program again with any of those. In the next images, the running instance is on top and the new instance is on bottom.

As the name implies, a named pipe server listens for connections based on the pipe name. By default, this library uses the application’s executable pathname, which you can see in the full-width screenshot above. I’ll truncate that in the other screenshots below.

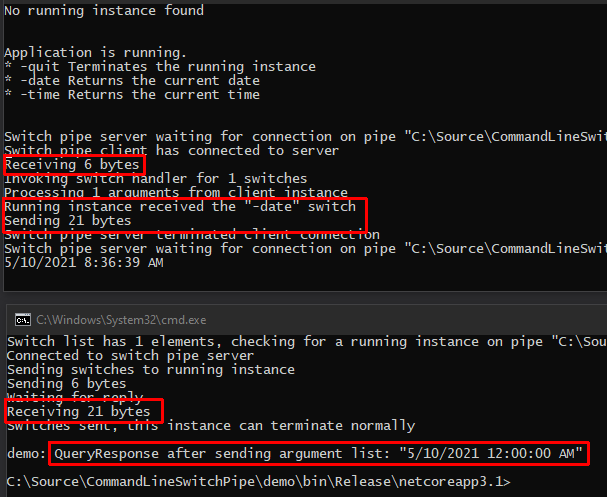

This is the output from the date switch. You can see that the running instance returned the date portion of the system clock. Since we have console logging enabled for demo purposes, you can see that the running instance receives 6 bytes (the “-date” flag and a separator character), and it sends 21 bytes (the date output).

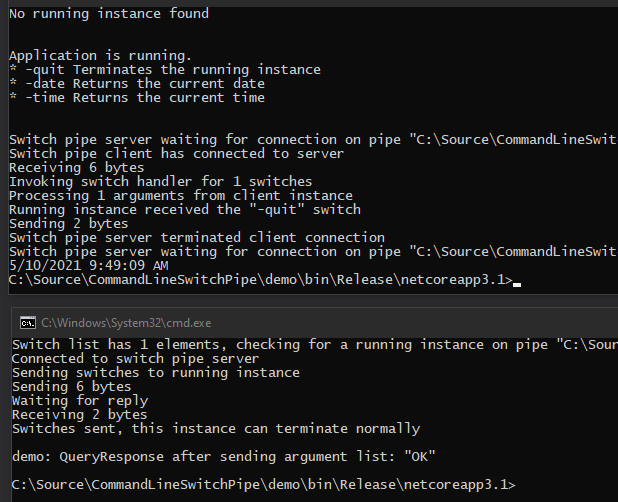

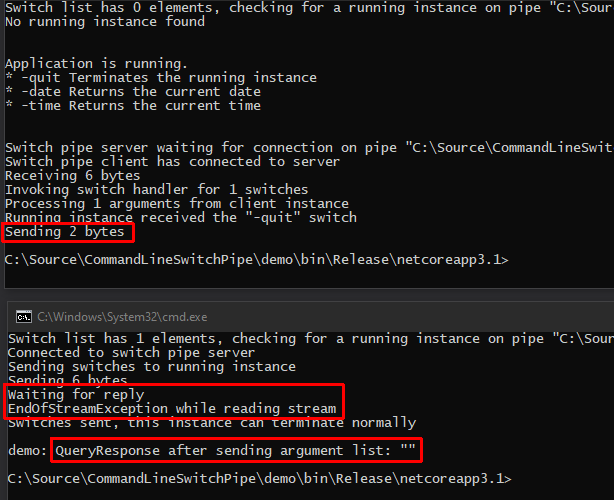

This is the output from the quit switch, which terminates the running instance:

Notice that the running instance sends back “OK” in response to the quit switch. This required adding a slight delay to the shutdown sequence of the running instance by using CancelAfter:

1

2

3

4

5

6

if (args[0].Equals("-quit", StringComparison.OrdinalIgnoreCase))

{

Console.WriteLine("Running instance received the \"-quit\" switch");

ctsRunningInstance?.CancelAfter(1000);

return "OK";

}

If the running instance quits immediately by calling Cancel, this would also terminate the pipe server before the new instance would have time to read the response, resulting in an exception. (Technically it’s probably a race condition.) This is probably an edge case specific to shutdown, but you may wish to keep that in mind to avoid alarming anyone with logged exceptions in a production environment.

Options

The static class has an Options property which provides a set of configuration points. All of these are explained in the repository README, so I won’t repeat all of that here. I believe the defaults should be adequate for most applications.

One option I do want to highlight, however, is the Options.Logger property, which can be set to an ILogger instance (Serilog, for example). If that is configured, activity, warnings, and errors will be written to the logger (subject to any minimum log-level settings, of course).

Conclusion

As I’ve started using this library in various (mostly incomplete) projects I have laying around, I’m finding the ease-of-use very handy – and I’m taking advantage of the response capability more than I expected. It’s nice to be able to query a running instance. In fact, in most cases I add a “-query” switch followed by various things defining what the running instance should return.

I haven’t posted many articles lately, but I’m getting back into hobbyist programming (I often can’t talk about what I do at work) so hopefully I’ll have a chance to write more. Even so, I’m happy (and surprised) that Google stats shows I passed the 100,000 readers mark two months ago. Hard to believe.

I like hearing from people, if this library is helpful or useful to you, drop me a comment!

Comments