UPS Monitor - Battery Backup Event Notifications

Windows UPS support has a lot of room for improvement.

This article discusses my UPS Monitor (@Github) application, which provides notifications of battery backup events as Windows desktop pop-ups, email messages, and Windows Event Log entries. The README in the linked Github repository explains how to install and use the program, so if that’s all you care about, click the link and get started. This is about the technical details of the program.

I used battery backups with desktops in the 1990s and early 2000s, but that was before the popularity of USB. At the time, if a small UPS could communicate at all, it did so via COM ports and was relatively expensive. Commercial UPSes used network cards (and many still do today). Around 2004 or 2005 I went all-laptop until just a few years ago, at which point I decided to build a beefy desktop machine. Recently we moved to an older neighborhood (houses from the 1930s and 1940s) and I found the power is much less reliable here. I bought a pair of APC SmartUPS 1500s for our desktops, and a SmartUPS 1000 for our NAS and network equipment. These are USB-equipped.

At first I was pleasantly surprised to see that Windows immediately recognized my APC SmartUPS 1500 over USB. It showed the battery charge status in the Windows notification area, and all the same Battery and Power Configuration options available to laptops are also available on my desktop machine. In the world of laptops, connecting to AC power and disconnecting is a routine affair. But AC power problems on a desktop is another matter, and I quickly found myself wishing that Windows was more communicative about power events and other UPS information like battery health.

Disappointing Official Support

I hoped Windows might have secret settings buried somewhere to provide at least minimal notifications, but alas, after days of searching and reading, it seems that no such thing exists. I was a little surprised that the UPS driver doesn’t even write anything to the Windows Event Log. In fact, to my disappointement, the Windows battery drivers haven’t changed at all in almost two decades!

I remembered that APC has a product called PowerChute, and indeed this is mentioned in the limited documentation included with the device. Surely APC, a respected and venerable name in the battery backup business, offers software which provides a wealth of information, right? Sadly, no. This premium-priced product’s instructions references a URL leading to a very old version of the software. After digging through multiple links to newer and newer versions (sometimes jumping between the Personal and Business editions), I arrived at a warning that PowerChute will be unsupported after March 2024 – and looking at the products, in reality they haven’t been supported in many, many years.

Instead, Schneider Electric, the French company which bought APC in 2006, is pushing something called Serial Shutdown. This is a disappointing, clumsy, slow, browser-based UI that is delivered by an enormous (~291MB!) Java-based service. While it provides a little bit of detail about the UPS itself, it actually offers fewer power-outage options and notifications than the default Windows UPS support, if you can believe that. It’s also quite sad that it uses a self-signed SSL certificate, which leads to browser warnings, which are somewhat difficult to “approve” in modern browsers. Less-technically-inclined users may not figure out that it’s even possible to allow these and proceed to the application UI. The only positive note I have about the product is that it’s meant to be accessed remotely (meaning within a private network, it isn’t secure). In short, I uninstalled Serial Shutdown after less than one day. At least the uninstall worked flawlessly.

I also spent some time investigating third party freeware, most especially NUT, aka Network UPS Tools. But a friend of mine runs some large data centers and said it’s basically old and clunky, hard to set up, and more oriented to large networks than home usage. There were a couple of others I found which all seemed old and mostly unsupported, and aren’t really worth mentioning. (If you know of a good free or inexpensive product, please post a comment!)

As usual, it appeared that if I wanted something done right, I was going to have to do it myself.

How hard can it be?

UPS Monitor Overview

I’m going to start by getting straight into the app details, because I’m guessing most readers will be primarily interested in how the program works today. Towards the end, I’ll discuss some of the things I tried, the problems I encountered, and some ideas I’d like to try in the future.

As the repository README explains, there are actually two applications. There is a System Tray (aka Notification Area) program named UPSMonitor and a Windows Service named UPSMonitorService. The UI program’s job is to manage pop-up notifications visible to the user, maintain a log of the past 100 notifications, and provide access to notification history. All of the real work is done by the Windows Service, which is necessary to provide monitoring when no user is logged into the computer. This separation is required because Windows Services run in a special hidden session which is not able to present any interactive UI elements (a change that was made way back in the days of Windows Vista).

The current iteration of the application relies on the built-in Windows UPS support, which feeds data into the CIM/WMI database (discussed later).

The UI Application

The UPSMonitor System Tray program is a very simple app consisting of an icon and a right-click context menu with just two options: History and Exit. Note that Exit only ends the System Tray program, the Windows Service will continue to run. Clicking History pops open a simple dialog listing up to 100 timestamps of notifications sent by the service, and clicking any timestamp shows the text for that notification. Notification history is stored in the registry under HKLM\SOFTWARE\mcguirev10\UPSMonitor.

There isn’t much to say about the System Tray program, except that I was pleased that modern .NET WinForm support seems to be complete and stable. While I understand the age-old arguments against WinForms, and I agree that WPF programs are enormously more flexible and powerful (although I’m not sold on UWP or some of Microsoft’s other recent UI directions), the fact remains that WinForms is fast and efficent from a development-effort metric. Years ago I explored making a System Tray application with WPF, and if you compare the code, that’s an enormously complicated exercise compared to this app.

Internally, the System Tray program simply sets up a named pipe server and waits for a connection from the Windows Service. When a message is received, it is displayed as a pop-up, also known as a “Toast” (apparently when these were introduced in MSN Messenger, the “slide up” presentation reminded someone of a slice of bread popping up out of a toaster). Technically, this is a UWP feature, so it is necessary to create a dependency on the Microsoft.Toolkit.UWP.Notifications package.

After a pop-up has been shown for a few seconds, Windows moves it to the Application Notification area, accessible from a little speech-bubble icon at the right of the Task Bar. Clicking these entries normally pulls up the application that presented them, but this does nothing in UPSMonitor. Similarly, if the application isn’t running, Windows will start the app. To prevent this, the program clears its notifications before shutting down by calling the static method ToastNotificationManagerCompat.Uninstall().

The repository README has a screenshot of the actual notifications presented on my system. It shows the basic details of whatever battery is being monitored, and a brief power event where the UPS switched to battery backup, then returned to AC power.

The Windows Service: CIM/WMI

All of the interesting work happens in the Windows Service. Ultimately, the program’s battery information comes from something called CIM or the “Common Information Model”, which is sort of a queryable database of details about a machine’s hardware and software. For a very long time, Microsoft had the only implementation of this, formerly known as WMI (Windows Management Infrastructure), which first appeared in Windows 2000 and was based on the draft spec for CIM. Although CIM is highly generic and relatively shallow compared to WMI, it appears MS has chosen to limit themselves to CIM going forward. For now, Windows CIM support is just a thin layer over WMI, and everything WMI is still accesible, but it’s an open question about how long that will last.

Before I was aware of the change to CIM, I began by querying WMI. Below, you can see the WMIC command to query the WMI database, and what my PC knows about my UPS. Through a great deal of trial and error, as well as comparisons to various laptop battery data, I learned most of the fields are unreliable, duplicated, or simply never populated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

C:\> WMIC Path Win32_Battery Get * /Format:List

Availability=2

BatteryRechargeTime=

BatteryStatus=2

Caption=Internal Battery

Chemistry=3

ConfigManagerErrorCode=

ConfigManagerUserConfig=

CreationClassName=Win32_Battery

Description=Internal Battery

DesignCapacity=

DesignVoltage=26180

DeviceID=3S2211X10713 American Power Conversion Smart-UPS_1500 FW:UPS 06.0 / ID=1028

ErrorCleared=

ErrorDescription=

EstimatedChargeRemaining=100

EstimatedRunTime=39

ExpectedBatteryLife=

ExpectedLife=

FullChargeCapacity=

InstallDate=

LastErrorCode=

MaxRechargeTime=

Name=Smart-UPS_1500 FW:UPS 06.0 / ID=1028

PNPDeviceID=

PowerManagementCapabilities={1}

PowerManagementSupported=FALSE

SmartBatteryVersion=

Status=OK

StatusInfo=

SystemCreationClassName=Win32_ComputerSystem

SystemName=IG88

TimeOnBattery=

TimeToFullCharge=

While researching these values, it quickly became apparent that CIM was what I really needed, and when I started looking into ways to query CIM from .NET, I found myself at the PowerShell MMI repo, aka the Microsoft.Management.Infrastructure package – but those docs aren’t useful, they are just empty content that is auto-generated from the source code.

My first attempt to query CIM resulted in this error message:

The client cannot connect to the destination specified in the request. Verify that the service on the destination is running and is accepting requests. Consult the logs and documentation for the WS-Management service running on the destination, most commonly IIS or WinRM. If the destination is the WinRM service, run the following command on the destination to analyze and configure the WinRM service: "winrm quickconfig".

Although I said CIM is just a thin layer over WMI, in fact CIM is just an interface to Windows Remote Management, aka WinRM, which in turn relies upon WMI. I did a little research, and the docs pretty clearly indicate “quickconfig” is safe. The command is simple: winrm quickconfig (running as Administrator), but I provided a ConfigWinRM.cmd batch file anyway.

That also means that the application’s service depends on the WinRM service at startup (WinRM must already be running), which is reflected in the Create.cmd batch file which registers the Windows Service program (the deps= WinRM argument does this).

Retrieving battery information from CIM is very simple. This is in the BatteryData class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

// battery info query:

// select Name, Status, BatteryStatus, EstimatedChargeRemaining,

// EstimatedRunTime from Win32_Battery

private List<CimInstance> QueryCIM(string query)

{

using var session = CimSession.Create("localhost");

return session.QueryInstances(@"root\cimv2", "WQL", query).ToList();

}

Although the MMI assembly does have versions of these methods which are labeled “Async”, they are not .NET Task-based async methods. Instead, they return “observables”, so they can’t be awaited as you’d expect. Given that the program runs the query once per second at most, and it returns in subseconds, and I couldn’t find any documentation about safe and correct handling of these “observables” (see above: no real documentation is available…), I figured a blocking call was acceptable here.

Each returned CimInstance object is a collection of properties (key/value pairs) that describe, in this case, one or more batteries connected to the system. While the typical system only has a single battery, it’s easy to imagine a multi-battery scenario such as a laptop that is connected to a UPS at your home or office (of course, for CIM/WMI to “see” it, the UPS must also connected to the laptop over USB). For those edge cases, the program configuration lets you specify an optional Name to match as the battery to be monitored, otherwise it monitors the first battery returned by CIM.

As you can see from the sample query in the code comment above, we only use five battery properties:

- Name: The “friendly” or “display” name for the battery device. In practice this may include things like a device ID, so if you expect to use multiple batteries and need to specify a name, run a WMI query first to see what your “true” full battery Name property will be.

- Status: This represents the health of the battery device. Anything other than “OK” is reported as a warning. These are generic values WMI uses to describe the “health” of any object, and they include values such as “Degraded” and “Pred Fail” (predicted to fail). Any return from a problem state back to “OK” is also reported.

- BatteryStatus: This number indicates the charge/discharge state of the battery. Although WMI defines 11 possible values, it appears only 1 and 2 are used. These are officially “Other” and “Unknown”, but in practice they indicate “Discharging” (status 1) or “AC Power” (status 2), and the program reports them as such.

- EstimatedChargeRemaining: This is an integer representing a percentage charge level. The program uses this to send warnings at various low-charge states. As noted in the repo README, these should be set 1% higher than the Windows Power Configuration “action” levels, otherwise the “action” (like hibernation) may happen before the service can send a notification.

- EstimatedRunTime: This is an integer value expressed in minutes. Some batteries do not report this correctly. For example, my Dell XPS13 laptop reported over 71 million minutes, or 136 years! Because of this, the program reports any estimated run-time over 1440 (24 hours) as “unknown”.

There is another field, “Availability,” which also seems to indicate battery/AC status, but it changed just as consistently as “BatteryStatus” and the program only needs one indicator, and I figured “BatteryStatus” is less ambiguous.

The Windows Service: Quirks

I had to make some manual edits to the csproj file and the publish XML file. Specifically, using the MMI package requires a TFM (Target Framework Moniker) in the csproj naming a specific minimum version of Windows, net6.0-windows10.0.17763.0. Similarly, the publish XML required an OS-specific RID (Runtime Identifier) rather than the generic options listed in the Visual Studio UI, namely win10-x86 rather than win-x86.

I chose to publish this as a self-contained deployment (SCD). Since Microsoft has started shipping trimming, I tried running a build with that option selected, but it isn’t compatible with MMI. The build reports this error:

System.NotSupportedException: Built-in COM has been disabled via a feature switch. See https://aka.ms/dotnet-illink/com for more information.

That link isn’t even a little bit useful, but this Q&A on StackOverflow explains it.

Trimming is still basically experimental, several assemblies the program needs aren’t compatible with SCD anyway, and the un-trimmed build isn’t that big, so it’s a minor issue. (Trimming also didn’t work for the System Tray applications, for what it’s worth.)

The Program.cs is pretty typical for a .NET Windows Service, except that I’m using .NET Dependency Injection, so some of the classes are registered as DI services. C# doesn’t support async constructors, which presented a bit of a dilemma – my BatteryState service needs to execute some async calls before it can be used, but in theory the DI container controls object lifetime. Fortunately this is a singleton, so I added a simple IAsyncSingleton interface and called a helper method before allowing the app Host to start:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

await InitializeAsyncSingleton<BatteryState>(host);

private static async Task InitializeAsyncSingleton<ServiceType>(IHost host)

=> await

(host.Services

.GetRequiredService(typeof(ServiceType))

as IAsyncSingleton)

.InitializeAsync();

Finally, although the service writes notifications to the Windows Application Event Log, it doesn’t register a custom Source. That requires admin rights, and it just wasn’t important to me. Events are written with ID 9001 which makes them easy to search for.

The Backstory

As I mentioned in the introduction, Windows support for UPS battery backups is rather uninspiring, to put it politely. Since the device is connected over USB, I wondered if I might simply query or monitor it that way. The APC communications protocol is pretty simple. The Network UPS Tools website documents it here, and I found several other (newer) sources that matched that information.

The first problem is that the UPS driver keeps that USB connection in a total headlock. I didn’t try it myself, but I found numerous discussions indicating it’s completely impossible. The recommendation was always to first disable all OS support for the UPS.

Since the Windows UPS driver is so primitive and neglected, I decided I might give that a shot, and I ran headlong into the next big problem: USB support in Windows is simply terrible and in .NET it is completely non-existent. I found three reasonable-looking third-party .NET libraries for working with USB. The first one, Device.Net, is “on pause” because the dev doesn’t feel like he was getting enough support from others. The second one, WinUSBNet, appears to have been abandoned, and has other problems for my purposes such as WinForms dependencies (which aren’t going to work in a Windows Service). Finally, I had the highest hopes for the actively-maintained LibUsbDotNet, but the sample code didn’t work, I couldn’t really make heads or tails of the limited documentation, and the person who replied to my inquiries curtly informed me it “isn’t a support forum” (I was reporting that the demos don’t work…).

So, eventually I gave up on the idea of direct USB communication. I still want to figure out how to do this (which will completely replace the OS battery support), but as you can see with this 1.0 release, WMI-based polling achieves my most important goal: getting notifications.

Another source of disappointment is the byzantine mess of registry entries making up the Windows Power Configuration groups and settings. It seems to be undocumented, and I haven’t been able to find anyone who understands it. There is a lot of similar code out there which purports to read these settings, but none of it works right (it all returns the defaults rather than the active configuration). I was hoping to use those settings in my application, but that goes on the “TODO” list as well.

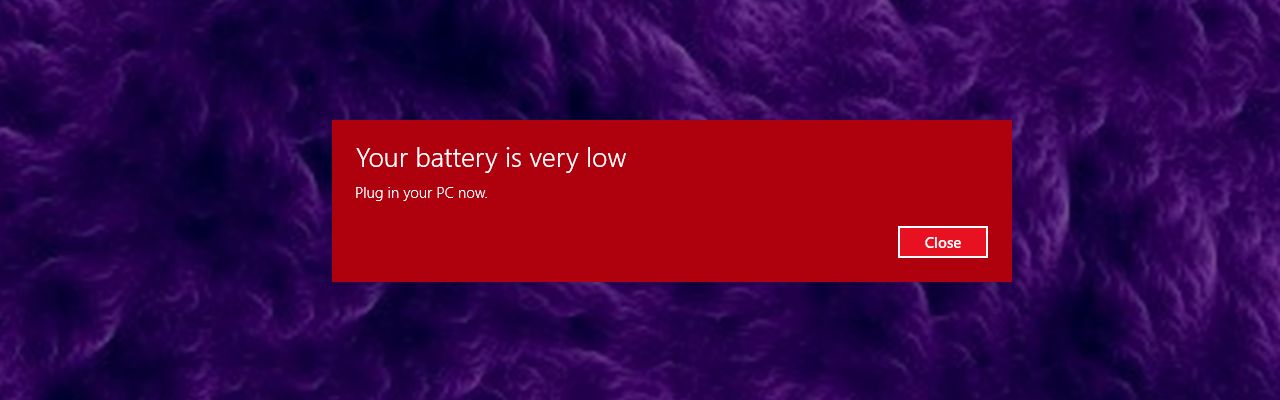

Speaking of Power Configuration, Windows seems to have a very long-standing bug with USB-connected battery backups. For some reason it will occasionally lose track of the battery charge level and begin showing low-battery warnings like the one in the header image for this article, even though the battery is nearly- or fully-charged (and even the System Tray battery icon shows a full charge). Often, it shows this message over and over, blocking any attempt to get work done. It also leaves a mystery window with the Windows Explorer icon in the Task Bar which can’t be opened/accessed. The fix is to disable the “Plugged In” low-battery notifications in the active Power Configuration. Just another example of the sad state of Microsoft’s attention to basic features of their “flagship” operating system.

There is a third oddity with Windows Power Configuration and a UPS connected over USB. Typically the complex command line program powercfg is used to manage these settings and to investigate the condition of your battery, but it doesn’t work with a USB battery backup. The powercfg /batteryreport command generates an HTML report that is basically empty. More neglect from Redmond.

Finally, Windows provides a set of CIM-driven Win32 power event notifications, and I want to explore those as an alternative to the current polling-based approach. Some of the power events are just flickers that are probably too brief to register with polling – I hear the UPS click back and forth once and it’s over in a tiny fraction of a second (often too brief to even mess up clocks in the kitchen; I suspect these may actually be voltage surges or drops). I simply don’t know whether those would have generated Win32 events. The UPS onboard LCD display keeps track of an event counter – mine currently shows 18 events and I have no idea what most of them were (which is actually another argument in favor of writing my own USB communications).

Conclusion

I’ve long been a critic of Microsoft’s apparent lack of interest in maintaining their dominance of the desktop, and everything mentioned in this article could be a poster child for that problem. That disinterest leaves me with a pretty large wish-list of complicated “TODO” items, but the first release of UPS Monitor solves my basic problem: finding out when my battery backup is activated, and maintaining awareness of battery charge level and overall health.

If you find it useful, or you have questions, ideas, or suggestions, please leave a comment. Enjoy.

Comments