Working With Multi-Target .NET Solutions

A quick review of working with multi-targeted projects and solutions in VS2017.

Recently I decided to migrate some Azure Functions V1 projects to Azure Functions V2. Everything in this particular system uses Serilog for logging activity and errors, but Azure Functions V2 is .NET Core-based. The use of the old .NET Framework ConfigurationManager by the SQL Server sink means any subsequent attempt to use the newer Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration namespace results in a runtime error. Since logging is one of the first things any application configures, the SQL sink inevitably wins, and the Azure Functions V2 runtime crashes.

Since the Serilog ecosystem is open source, I decided to tackle the upgrade myself. Serilog has both .NET Framework and .NET Core consumers, and the SQL sink is already a multi-targeted solution. Because the sink supports .NET Framework 4.5.x which pre-dates .NET Standard 2.0, and since newer .NET Framework users may still prefer the old static configuration approach, I decided to stick with the multi-targeted approach.

The problem I faced is that much of the code required to use each config system is different, but at a high level Serilog does provide configuration abstraction, so I wanted to provide multiple implementations within a single project, all while minimizing changes to the older, working code. I could use zillions of #if tests but I figured there must be a better way. Last year, Oren Novotny published this article about working with multi-targeted solutions, something which Microsoft has almost zero useful documentation about, and something which is only loosely supported by Visual Studio 2017. Oren goes into a lot of detail about different ways to work with multi-target projects, but the part that caught my eye was two completely different implementations of a class – same names, same namespace, differentiated only by the folder they’re in and the build target – but still visible and useable within Visual Studio.

Consequently, this article isn’t about fixing the Serilog library, it’s about how to set up a multi-targeted project that uses target-specific versions of the same file. This is really one of those “notes to myself” articles, but perhaps these notes will help others.

Code related to this article can be found on Github here.

Sample Solution

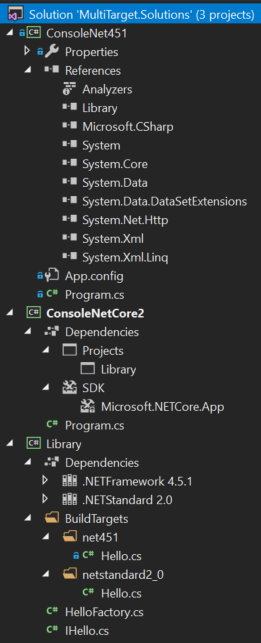

The sample solution consists of a multi-target library which I’ve cleverly named “Library”, and it exposes an IHello interface, a static HelloFactory class, and two implementations of a class named Hello, one targeting .NET Framework 4.5.1, and the other targeting .NET Standard 2.0. The factory returns an instance of the class, and the class just emits a string identifying which framework was targeted. Additionally, the solution contains two console programs, ConsoleNet451 and ConsoleNetCore2 targeting the frameworks according to their name.

As you can see above, the .NET Framework console program has a project reference to Library and the .NET Core console app lists Library as a project dependency. You can also see that the Library project itself targets both .NET Framework 4.5.1 and .NET Standard 2.0.

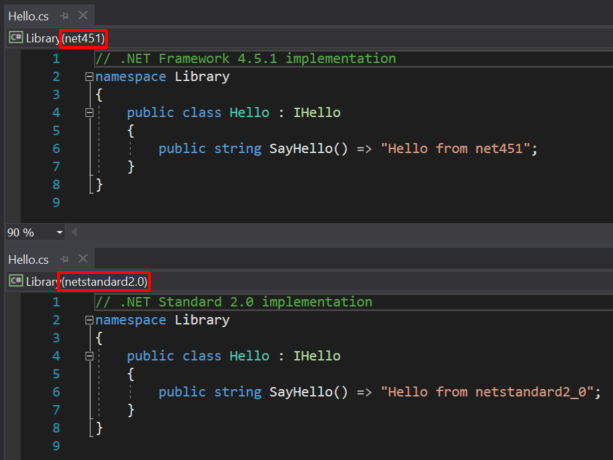

I created a BuildTargets folder as the home for any files that would differ according to the target – in Microsoft-speak, by Target Framework Moniker, or TFM. If we open both Hello.cs files side-by-side, things get interesting.

You can see the namespaces and class names are the same, but Visual Studio doesn’t flag them as duplicates – as the red outlines show, VS recognizes they belong to different TFMs – different build targets. They won’t be built into the same assembly, so there is no conflict.

Unfortunately, that subtle indicator and the ability to list multiple dependencies in Solution Explorer are pretty much the only UI support you’ll get in VS 2017 for multi-targeting. The rest of the article explains how to get this working.

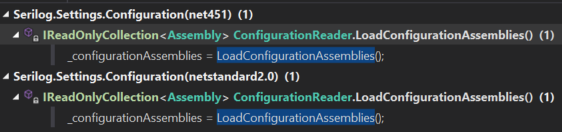

Update: As I spend more time working on multi-targeted projects, I keep finding new places where the UI supports this. For example, the Find All References window separates search results by target:

The other code is pretty simple stuff. The HelloFactory creates and returns a new Hello, and the console programs call that and output the SayHello return value, then pause for input. Each Hello implements the IHello interface, but this isn’t strictly necessary, the static HelloFactory returns IHello but creates with a reference to Hello.

C# Project or MSBuild?

The new, so-called SDK-style C# csproj file is actually an MSBuild file format. This is the file for our sample, which we’ll review section by section.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

<Project Sdk="Microsoft.NET.Sdk">

<PropertyGroup>

<TargetFrameworks>netstandard2.0;net451</TargetFrameworks>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition="'$(TargetFramework)' == 'netstandard2.0'">

<DefineConstants>NETSTANDARD</DefineConstants>

</PropertyGroup>

<PropertyGroup Condition="'$(TargetFramework)' == 'net451'">

<DefineConstants>NETFRAMEWORK</DefineConstants>

</PropertyGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<Compile Remove="BuildTargets\**\*.*" />

<None Include="BuildTargets\**\*.*" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup Condition="'$(TargetFramework)' == 'netstandard2.0'">

<Folder Include="\netstandard2_0\" />

<Compile Include="BuildTargets\netstandard2_0\*.cs" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup Condition="'$(TargetFramework)' == 'net451'">

<Folder Include="\net451\" />

<Compile Include="BuildTargets\net451\*.cs" />

<Reference Include="Microsoft.CSharp" />

</ItemGroup>

<ItemGroup>

<None Include="IHello.cs" />

</ItemGroup>

</Project>

The first <PropertyGroup> lists semicolon-separated TFMs – in our case, .NET Standard 2.0 comes first, and .NET Framework 4.5.1 comes next. Currently the order of the TFMs does matter, Visual Studio sets a lot of default assumptions (such as what Intellisense shows) based on the first TFM. Oren’s article goes into some detail about this – under the covers the current build config (such as Debug | x64) has the TFMs appended to them, but the UI doesn’t give you a way to change it. Note the <TargetFrameworks> tag is plural – the single-target tag you’ll find in a normal project file is singular.

Since there is no UI support, the only way to create a multi-target project file is to edit the csproj by hand. When you save the changes, you’ll see a warning and the project will be re-loaded.

The second and third <PropertyGroup> sections aren’t actually used by the sample solution, but they demonstrate how to create your own constants for use with directives like #if. In this example, NET451 and NETSTANDARD2_0 would already be defined by MSBuild based on the TFMs, but it might be easier to use a less-specific custom constant like those shown here.

The first <ItemGroup>’s <Compile> tag tells MSBuild that, by default, it should ignore everything in the BuildTargets folder (including subdirectories, thanks to the ** recursive-globbing wildcard). It is then followed by the <None> tag which re-includes that same path specification. Although this isn’t well-documented by Microsoft, this tag causes the contents of that folder to be shown in Solution Explorer. This use of <None> is a bit of a hack, it really tells MSBuild the pathspec doesn’t have any defined build role – it isn’t to be compiled, it isn’t published content, and and so on – but it’s still part of the project.

The second and third <ItemGroup> sections contain Condition attributes that reference TFMs. (Notice the difference in syntax for .NET Standard … the TFM syntax is netstandard2_0 but for some reason the Condition syntax is netstandard2.0). The <Folder> tags just add the folders to the solution, there is no particular reason to tie them to the TFM. The <Compile> tag is the important part here: it tells MSBuild which branch under BuildTargets to include in the build.

Finally, in the net451 conditional-TFM <ItemGroup> you can see an example of a project-level reference: .NET Framework projects require a reference to Microsoft.CSharp (whereas newer .NET SDK projects do not). We could do things like reference different versions of JSON.NET for each TFM, or include completely different libraries specific to each TFM (in the same way my Serilog change will reference Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration in the .NET Standard section). Here again you should edit by hand because the limited UI support in Visual Studio for multi-target projects comes into play. The NuGet extension will only update groups relating to the first TFM listed.

Conclusion

Once you know all the secret handshakes, it’s pretty easy to get a multi-targeted project up and running. Hopefully later releases of Visual Studio will give us a better UI/UX around this functionality.

Comments