Distributed Caching with Microsoft Orleans

A high-scale IDistributedCache service based on Microsoft Orleans with ADO persistence.

This article demonstrates how to implement IDistributedCache using the Microsoft Orleans platform. Compared to setting up something like Redis, it is ridiculously easy to use, and high scalability is a central feature of the platform. A local-development setup works exactly the same way a custered multi-server installation works.

The source for the article uses the pre-release version of .NET Core 3.0 RC1, but when that finally goes to full-release status, I will publish McGuireV10.OrleansDistributedCache as a NuGet package. The code for this article is in my GitHub MV10/OrleansDistributedCache repository.

Update 2019-11-04: The code has been updated to use .NET Core 3.0 and Orleans 3.0 release builds. The NuGet package is available and a new article has been posted about this: Orleans Distributed Cache NuGet Release. There are several updates in the article below, as well.

Orleans is one of those projects people refer to as a “hidden gem” – it isn’t widely known or even widely used, but once you get the hang of using it, you wonder how you got along without it. The Orleans repo features the dry description, “Distributed Virtual Actor Model” and the documentation is simultaneously very good and very bad. Good in the sense that it goes beyond the “API listing” that is so common these days, but bad because it’s organized oddly and is not up-to-date in places. Orleans was originally designed by Microsoft Research as the services platform behind mega-hit multi-user games like Halo and Gears of War, but the current version (2.4.x, with 3.0 under active development) has matured into an excellent foundation for general-purpose microservice frameworks.

The actor model dates back to 1973, making it one of the oldest software concepts still in widespread use today. The description in that link is worth reading if you aren’t familiar with it. A very popular actor framework is AKKA.NET, which is a port of the Java AKKA framework. What Orleans brings to the table is virtualization. In systems like AKKA.NET, your code spends a lot of time managing actor lifecycles, communications, and other “plumbing”. With Orleans, all of that goes away. You literally just ask for a reference to your actor (as the linked article explains, all actors have a unique key) and start calling its methods. Orleans does the rest – making sure it exists, loading and unloading them, persisting and restoring state, and even managing all of this between multiple servers in the cluster. It’s encapsulation taken to extremes, and it happens to be great for scale-out, which is exactly what you want for microservices.

When people think “microservices,” they probably don’t think “distributed caching” but it’s certainly handy to have. Moreover, the state-persistence features of the Orleans architecture is already a kind of distributed caching. What we’re really doing here is wrapping that up with the standardized ASP.NET Core IDistributedCache interface. This is not a new idea, but all of the examples I found online had various bugs or problems, and none of them were current.

Basic Concepts

There are several concepts in Orleans that you should understand before we dig in. The details are beyond the scope of this article, however. Read the Orleans documentation for a more comprehensive introduction. There are other Orleans concepts that we won’t get into at all today, such as Event Sourcing, interleaving, streams, reminders, timers, and more. Some of those are very important, such as server configuration (my silo and client examples are very bare-bones).

In Orleans, each actor is called a grain, and silos are the host servers that manage and execute grains. There are stateless grains as well as stateful grains. Grains can communicate with one another, and client applications can also communicate with grains. (From a programming standpoint, you’re just calling methods on a proxy to the grain; Orleans does use messaging but it’s completely transparent to your code.)

Various “Storage Provider” packages are available to target different persistence models. As mentioned earlier, the grain lifecycle is completely managed by Orleans silos. “Deactivation” is when a silo decides a grain should be persisted to storage and unloaded from memory. This usually happens due to memory pressure. For this article, we are using the ADO.NET-based SQL Server library, but Orleans offers many Storage Provider implementations, including things like Azure Blob Storage which are very different from traditional RDBMS storage.

Silos register themselves in a database, and clients find and connect to silo servers by connecting to the same database. A silo database can persist many different types of grains, but caching tends to be a high-traffic activity, so like most distributed caching systems with persistent state, it’s probably best to use a dedicated database for the cache.

A cluster is automatically formed when multiple silos running on different servers share the same Orleans database. Silos communicate between themselves, and the cluster itself is a completely self-managing systems. Clustering is how Orleans achieves cloud-grade scale-out capability.

The Cache Grain

In the OrleansDistributedCache library, a grain represents a single cached value. The key used to identify the cache entry is directly re-used as the grain key as well. The grain interface and concrete implementation are in the files IOrleansDistributedCacheGrain and OrleansDistributedCacheGrain respectively.

The grain interface is fairly self-explanatory, with Set, Get, Refresh and Clear methods:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public interface IOrleansDistributedCacheGrain<T> : IGrainWithStringKey

{

Task Set(Immutable<T> value, TimeSpan delayDeactivation);

Task<Immutable<T>> Get();

Task Refresh();

Task Clear();

}

Despite returning Task, you may notice we don’t follow the convention of adding Async to the method names. This interface is exactly the reason I’m not a fan of that convention. Whether or not the the async keyword is required is an implementation detail that can’t necessarily be known at the interface level. If the Set method is using a simple in-memory ConcurrentDictionary, there will be no asynchronous calls, but if the implementation is doing database I/O, then async is likely. The actual implmentation ends up with a mix of each (for example, Set is asynchronous but Get is synchronous).

Whenever possible, grain state should be wrapped in an Immutable<> object. This tells Orleans that the state will not change when Orleans is persisting the data. This improves performance since Orleans will try to deep-copy non-Immutable data prior to serialization. Since IDistributedCache works with byte-array copies rather than direct references to the data to be stored, it’s safe to assume the data is always immutable.

The implementation begins with a [StorageProvider] class attribute. A silo can host multiple Storage Providers, each pointing to different data stores. This attribute is how a grain declares a dependency on a specific Storage Provider. I think a hard-coded string is a bit of a leaky abstraction, but it works. I tried to mitigate this a little by using a static string costant in the cache service class:

1

2

[StorageProvider(ProviderName

= OrleansDistributedCacheService.OrleansDistributedCacheStorageProviderName)]

The class itself derives from the stateful Grain<T> class and implements the cache grain interface shown above:

1

2

3

public class OrleansDistributedCacheGrain<T>

: Grain<Immutable<T>>,

IOrleansDistributredCacheGrain<T>

A stateful grain must declare the type of stateful data it will manage. This can be a custom class, although here the only state we manage is Immutable<T>. Within the grain code itself, this is exposed by the State property (which is part of Grain<T>). You can see this with the very simple Get method, which simply returns State:

1

2

public Task<Immutable<T>> Get()

=> Task.FromResult(State);

The Set method simply assigns the input value directly to State, but there is a little more going on in that method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public async Task Set(Immutable<T> value, TimeSpan delayDeactivation)

{

State = value;

this.delayDeactivation = (delayDeactivation > TimeSpan.Zero) ? delayDeactivation : options.DefaultDelayDeactivation;

if (options.PersistWhenSet)

await base.WriteStateAsync();

DelayDeactivation(delayDeactivation);

}

The grain base class method DelayDeactivation does exactly that – sets the minimum amount of time before the silo can deactivate that grain. In the Set method we apply the requested delay, or if the delay was TimeSpan.Zero (which you’ll see again in the IDistributedCache implementation), we use the delay defined by configuration.

Configuration also sets a boolean PersistWhenSet flag. When true, the grain state (the cached value) is immediately persisted to the database. Otherwise the value will not be persisted until the silo decides to deactivate the grain (which may never happen). As long as your cached data is relatively small and simple, setting this to false is unlikely to produce any important performance gains unless you’re building a very high-traffic system.

The Refresh method just re-loads state from the database, which isn’t generally necessary in an Orleans grain: it’s just there to provide parity with the IDistributedCache methods.

Finally, Clear calls another grain base class method, ClearStateAsync, which nulls out the State data. It also calls DeactivateOnIdle which effectively deactivates the grain immediately. (In Orleans, “idle” is when the grain has processed all messages in the grain’s queue – so technically if several clients accessed this grain at approximately the same time, the deactivate would be slightly delayed.)

And that is literally all there is to caching data from a pure Orleans perspective.

The Cache Service

The interface your code will use (and ASP.NET Core, if you’re using it in a web app) is implemented by the OrleansDistributedCacheService class. ASP.NET Core knows nothing of Orleans and grains, which is why we need an IDistributedCache implementation to bridge that gap. Since this is a well-known interface, I won’t say too much about most of this implementation, the code is self-explanatory. However there are a couple of points you should notice.

ASP.NET Core uses dependency injection everywhere. Notice the constructor requires an IClusterClient object. You must create this and register it during application start-up. We’ll see an example of that later when we cover the client application:

1

2

public OrleansDistributedCacheService(IClusterClient clusterClient)

{ ... }

Let’s take a quick look at how we get and use a grain reference:

1

2

public async Task<byte[]> GetAsync(string key, CancellationToken token = default)

=> (await clusterClient.GetGrain<IOrleansDistributredCacheGrain<byte[]>>(key).Get()).Value;

You can see we simply call GetGrain with the type of grain we want (which in our case includes the type of data we’re caching, a byte array), and we provide a key that identifies the grain. Then we’re calling our cache grain’s Get method. That returns an Immutable<byte[]>, so we then call the Value property exposed by Immutable to return the original data (the byte array).

If you scroll all the way to the end of this class, you’ll see something a bit unusual. I decided the synchronous methods on IDistributedCache will be unavailable. The [Obsolete] attribute will cause design-time and build warnings, and of course, it will throw at runtime.

1

2

3

[Obsolete(Use_Async_Only_Message)]

public void Set(string key, byte[] value, DistributedCacheEntryOptions options)

=> throw new NotImplementedException(Use_Async_Only_Message);

Why do this? The underlying grain methods are asynchronous, and sync-over-async can’t be done safely. Everything in ASP.NET Core is fully async-capable, so there is no good reason to ever use the synchronous methods.

The Cache Extension

Finally, we get to the helper-methods in OrleansDistributedCacheExtensions and the configuration features in the OrleansDistributedCacheOptions, which follows the .NET Core Options pattern.

To use the cache system with the default settings, you need only call this in your ConfigureServices method:

1

services.AddOrleansDistributedCache();

However, the two configuration features mentioned in the previous section can be set by this call:

1

2

3

4

5

services.AddOrleansDistributedCache(opt =>

{

opt.DefaultDelayDeactivation = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(20);

opt.PersistWhenSet = true;

});

And that is all there is to the Orleans Distributed Cache library.

The Orleans Database

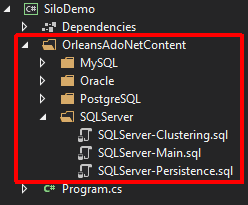

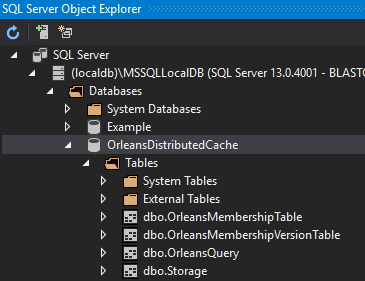

A minor chore is creating the database that your Orleans system will use. For this article, we’ll use the local SQL Express instance installed with Visual Studio. Orleans setup is a bit unusual in that the SQL scripts are provided as content nodes in the ADO.NET NuGet package. The result is that a folder full of SQL scripts is added to the project that references the NuGet packages:

The docs only mention this briefly, which is very easy to overlook. The team is aware that this is unusual and they’re considering alternatives, so this may change with future releases. I know I ended up searching the source repositories for the scripts, which is apparently common.

Anyway, pop open your Sql Server Object Explorer window, create a new database named OrleansDistributedCache, and run the SQLServer-Main, SQLServer-Clustering, and SQLServer-Persistence scripts on your new database (in that order, because “main” creates a table used by the other two scripts).

Silo Demo

The silo in this article is is not a production-quality silo implementation. It’s just something you can run locally while you play with the system. Never expose an Orleans silo directly to the Internet or to any untrusted network. Silos are not secure and they are not intended to be used that way. Note also that silos do not currently support SSL/TLS security, although this is planned for the upcoming 3.0 release.

Silos are just console programs. Silo startup follows the extensible “builder” pattern seen elsewhere in .NET Core. You add various extension packages to your project which provide a fluent lambda-configured setup process, then conclude with a build-and-run call that brings it all together. This example uses the newer generic HostBuilder (the same thing ASP.NET Core is moving to, replacing the former WebHostBuilder class), and it also makes use of the UseOrleans extension which is currently undocumented.

The outer portion looks like this, which should remind you of Program.cs for starting an ASP.NET Core application. The stuff at the end just sets up a console-based logger (Orleans logs everything, it’s kind of amazing to watch it work).

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public static Task Main(string[] args)

{

return new HostBuilder()

.UseOrleans(builder => builder

// extension calls omitted

)

.ConfigureServices(svc =>

svc.Configure<ConsoleLifetimeOptions>(opt =>

opt.SuppressStatusMessages = true

)

)

.ConfigureLogging(builder => builder.AddConsole())

.RunConsoleAsync();

}

The important bits go inside the UseOrleans section, which we’ll cover next. First we add clustering support. The Orleans team uses the term Invariant to refer to the ADO.NET namespace where support like SQLConnection and SQLCommand can be found. In this app it’s hardcoded to System.Data.SqlClient in a static string.

1

2

3

4

5

.UseAdoNetClustering(opt =>

{

opt.ConnectionString = ConnectionString;

opt.Invariant = StorageProviderNamespace;

})

Next, we set up the Storage Provider which persists our cache grains. This is where the Storage Provider name is used again, which was referenced in the grain class itself by the [StorageProvider] attribute. The ADO.NET package can persist data in binary, JSON, or XML formats. Here I’ve selected XML just for illustrative purposes, although a real cache implementation would probably stick with binary serialization. (XML serialization could be useful for more traditional custom-POCO grain state storage, where you could leverage SQL Server’s built-in XML support.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

.AddAdoNetGrainStorage(

OrleansDistributedCacheService.OrleansDistributedCacheStorageProviderName,

opt =>

{

opt.ConnectionString = ConnectionString;

opt.Invariant = StorageProviderNamespace;

opt.UseXmlFormat = true; // update: don't do this unless you really need it!

})

Update 2019-11-04: Be certain the data you’re storing can be safely round-tripped if you use XML or JSON serialization. This caused issues in later testing, described in the newer article about this cache system: Orleans Distributed Cache NuGet Release. Keep in mind that Orleans is currently using custom serializers. Being able to round-trip your data on other platforms doesn’t guarantee that Orleans can handle it. In particular, wiring up an XML-serialized cache to ASP.NET session (demonstrated later in this article) will cause problems which are detailed in the new article.

Now we’ll set a couple of cluster options. The documentation glosses over these completely. They’re used to support what Fowler (and Azure) calls the “blue/green” depolyment model. If you aren’t using this (its popularity is declining), the two values can be the same. Otherwise the ServiceID is effectively an application identifier (same for blue/green), but the ClusterId identifies your “blue” or “green” cluster servers. Meanwhile the shared ServiceID ensures both clusters use the same underlying storage.

1

2

3

4

5

.Configure<ClusterOptions>(opt =>

{

opt.ClusterId = ClusterId;

opt.ServiceId = ServiceId;

})

Finally, we tell the silo which grains it will manage using a somewhat esoteric corner of .NET Core called application parts. Like many .NET Core libraries, this isn’t specific to ASP.NET Core in any way, but for some reason Microsoft slots it there anyway. In my opinion, this point in the silo setup is approximately where the grain/storage association should be made, not within the grain itself, and I plan to open a GitHub issue to discuss this with the Orleans team.

1

2

3

.ConfigureApplicationParts(parts =>

parts.AddApplicationPart(typeof(OrleansDistributedCacheGrain<>).Assembly).WithReferences()

)

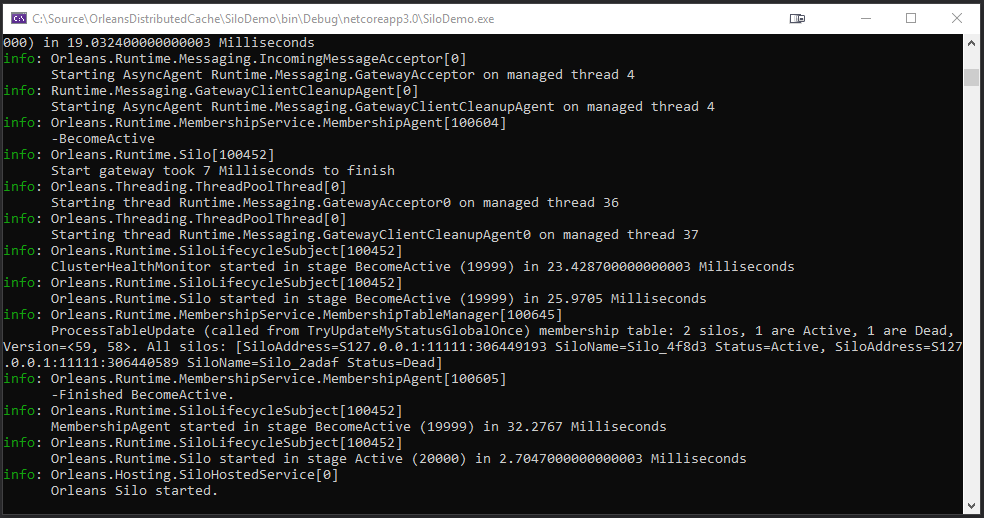

When you run the silo project, a console window will open and begin spewing tons of log entries. Hopefully they’re all “green-is-good” info entries. Use CTRL+C to exit the silo program (it uses task cancellation to shut down cleanly, you’ll see a bunch of additional log entries in response to your keystrokes).

This silo is hard-coded to use localhost, but if you change it to listen on specific IPs and run multiple copies on different machines, you’ll have an Orleans cluster running with exactly the same code. Clustering and scale-out load balancing is built into the very core of Orleans.

Client Web App Demo

Update 2019-11-04: Although you can use this cache with ASP.NET session state storage, you shouldn’t for a variety of reasons. To be clear, you can use the cache directly, just don’t wire it up to session, as shown below. More details are available in the newer article: Orleans Distributed Cache NuGet Release.

Now we’re ready to set up a web app to demonstrate our Orleans cache. The project is called SessionStateDemo because I wanted to show that it’s truly 100% ASP.NET Core friendly. There are plenty of reasons to avoid using session state in a web-based app, but a quick-and-easy demo isn’t one of them! This project began as the empty Razor Pages template in ASP.NET Core 3.0 RC1, and it’s surprisingly easy to add this cache service to the project.

First we modify Program.cs. We have to create an IClusterClient object, then register it for DI (recall that our IDistributedCache implementation declares a dependency on this in its constructor). You can see that’s a subset of the same setup we used for the silo, except we’re using a ClientBuilder instead of a HostBuilder, so I won’t go into detail about this.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

public static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

IClusterClient orleansClient = new ClientBuilder()

.UseAdoNetClustering(opt =>

{

opt.ConnectionString = ConnectionString;

opt.Invariant = StorageProviderNamespace;

})

.ConfigureServices(svc =>

svc.Configure<ClusterOptions>(opt =>

{

opt.ClusterId = ClusterId;

opt.ServiceId = ServiceId;

})

)

.ConfigureApplicationParts(parts =>

parts.AddApplicationPart(typeof(OrleansDistributedCacheGrain<>).Assembly).WithReferences()

)

.Build();

// the rest of Main goes here

}

Next we use that client object to connect to the silo (technically we’re connecting to a silo cluster, but in our case it’s a cluster of one). This code is very simplified compared to what you should do for a real app. At a minimum, you should catch exceptions which disposes and re-creates the client object, and you should implement some sort of retry policy. But since this is just a demo, we’ll take the easy route for the sake of clarity:

1

await orleansClient.Connect().ConfigureAwait(false);

Finally, we set up ASP.NET Core hosting. Notice that we add the client object as a singleton service so that the dependency injection system can populate the dependency when the distributed cache service is created.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

await Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args)

.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(builder => builder.UseStartup<Startup>())

.ConfigureServices(svc =>

{

svc.AddSingleton(orleansClient); // important!

svc.Configure<ConsoleLifetimeOptions>(opt => opt.SuppressStatusMessages = true);

})

.ConfigureLogging(builder => builder.AddConsole())

.Build()

.RunAsync();

Next, we update Startup.cs with just three additions – one is a call to our AddOrleansDistributedCache extension method, and the other two set up ASP.NET Core session state support. The rest of the code is straight out of the Visual Studio solution template:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddRazorPages();

// add this

services.AddOrleansDistributedCache(opt =>

{

opt.DefaultDelayDeactivation = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(20);

opt.PersistWhenSet = true;

});

// add this

services.AddSession(opt => opt.IdleTimeout = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(20));

}

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IWebHostEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

else

{

app.UseExceptionHandler("/Error");

app.UseHsts();

}

app.UseHttpsRedirection();

app.UseStaticFiles();

// add this

app.UseSession();

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthorization();

app.UseEndpoints(endpoints =>

{

endpoints.MapRazorPages();

});

}

Finally, we’ll modify the Index page to demonstrate the cache system. In the model, we’ll add a constant, a couple of fields, and change the OnGet method as shown. This produces the cached byte array using the new JSON serializer built into ASP.NET Core 3. It isn’t as flexible as JSON.NET (issue) but it performs better and will eliminate version-specific dependencies that have been causing problems for .NET developers for almost three years.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

private const string sessionKey = "FirstVisitTimestamp";

public DateTimeOffset DateFirstSeen;

public DateTimeOffset Now = DateTimeOffset.Now;

public async Task OnGet()

{

await HttpContext.Session.LoadAsync();

if(HttpContext.Session.TryGetValue(sessionKey, out var sessionDate))

{

DateFirstSeen = JsonSerializer.Deserialize<DateTimeOffset>(sessionDate);

}

else

{

DateFirstSeen = Now;

HttpContext.Session.Set(sessionKey, JsonSerializer.SerializeToUtf8Bytes(DateFirstSeen));

}

}

Note the bizarre call to Session.LoadAsync. Without this, session calls will be synchronous, which is Very Bad for scalability purposes. I can’t begin to imagine what Microsoft was thinking when they designed session support this way. It has to be called everywhere that session is used. Most people don’t even know it exists, it’s barely mentioned in the docs, it isn’t something anyone would ever expect is needed, and of course, it would be tragically easy (even likely) to simply forget to call this throughout a real-world-sized app. Microsoft did eventually figure out everybody overlooks this, so there are backlogged plans to add some type of middleware filter to handle this for you, but it didn’t make the cut for Core 3.0.

Of course, given that my IDistributedCache implementation throws exceptions for the synchronous calls, you can’t accidentally overlook this ill-conceived requirement.

The last step is to show the two timestamps in the Index razor CSHTML:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

@page

@model IndexModel

@{

ViewData["Title"] = "Home page";

}

<div class="text-center">

<h3>Session State via OrleansDistributedCache</h3>

<hr/>

<p><strong>First visit: </strong>@Model.DateFirstSeen.ToString("O")</p>

<p><strong>Currently: </strong>@Model.Now.ToString("O")</p>

</div>

Show Me the Money

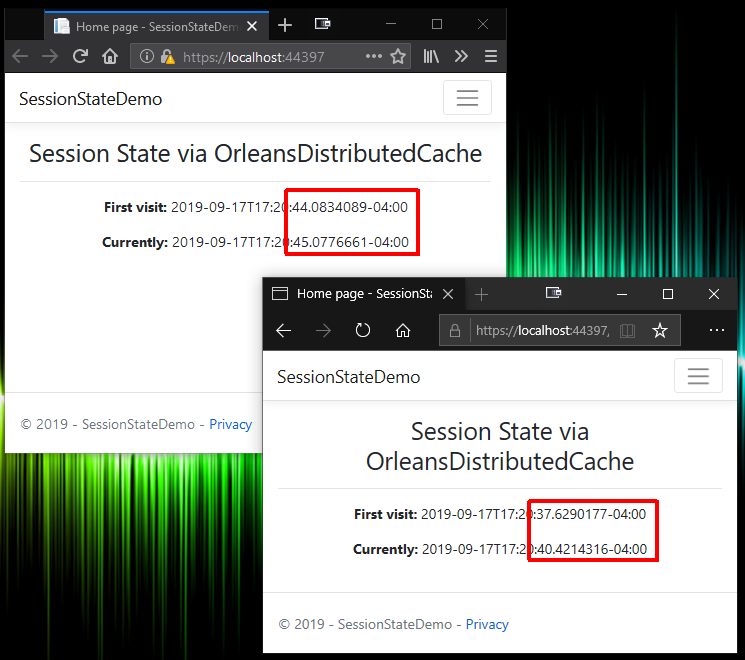

We have the silo running, so we fire up the web app in Firefox and are rewarded with a pair of very exciting timestamps on our index page. Refreshing the page demonstrates that the first value really was cached in session state because the second value (“Currently”) shows a later timestamp. We then open a second browser window (a different browser, this time Edge, since session is browser-wide) to demonstrate multiple sessions:

Update 2019-11-04: This only worked because the Silo I was running at the time didn’t specify XML serialization. Once again, read the new article if you want the details: Orleans Distributed Cache NuGet Release.

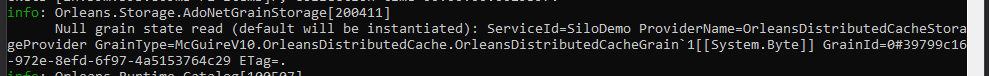

In the silo console window, you can see log entries describing cache grain activity. This entry was logged when a new cache grain is instantiated:

Conclusion

This is just the tip of the iceberg with Orleans. Earlier I mentioned that people make a big deal about “discovering” Orleans, and it is having the same effect on me. There are many systems which are nothing but grain-based microservices with a relatively thin web app wrapper. I also mentioned Orleans isn’t really a microservices framework, it’s more like a platform that enables the creation of a framework. This was a good project to get my feet wet with Orleans basics – I definitely look forward to working with it’s more service-platform-oriented features in the near future.

Comments