Orleans Distributed Cache NuGet Release

Releasing the caching library for Core 3.0 and and Orleans 3.0

This article discusses my NuGet package McGuireV10.OrleansDistributedCache.

The source can be found on GitHub at https://github.com/MV10/OrleansDistributedCache.

Several weeks ago I posted the article Distributed Caching with Microsoft Orleans which, as the title states, demonstrated how to build an implementation of IDistributedCache based on the silo and grain concepts of the Microsoft Orleans virtual actor framework. In that article I promised an update and NuGet package once .NET Core 3.0 was released, and to my surprise, Microsoft Orleans 3.0 was released at almost the same time. This is that article, but the process wasn’t quite as straightforward as it should have been.

If you just want to use the Orleans Distributed Cache package, the earlier article tells you everything you need to know. (And I’m updating that article with a couple of points I’ve learned during the processes described below.)

Updating to Release Packages

The dependency updates went pretty smoothly, although in few cases I had to guess which packages to update first. Unfortunately, when you’re using multiple NuGet packages which have dependencies on each other, figuring out how to get them all updated can be a trial-and-error hassle. There have been times when I simply unloaded the solution and modified the versions in the csproj with Notepad, then let the restore process sort it out, although it didn’t get that bad for these projects.

The OrleansDistributedCache project itself required moving from .NET Core 3.0 preview packages to the release packages for the caching, dependency injection, and options extensions. Then I updated to the Orleans 3.0 release packages (from 2.x) for the abstractions package (first, due to dependencies), the client support package, and the codegen package. I bumped the project version to 1.0.1 and ran another local build so that I had a new version for the demo projects to reference.

The three demo projects automatically picked up the release version of the .NET Core and ASP.NET Core 3.0 frameworks. I’m actually not sure how that mechanism works since they were created targeting the preview-release frameworks. Prior to updating the projects, I had uninstalled the preview frameworks. Later I found out that the release-version installers are supposed to do that automatically.

The Silo, ASP.NET Core, and Stand Alone demo projects required updating to the .NET Core 3.0 and Orleans 3.0 release packages as well, and then I pulled in the 1.0.1 Orleans Distributed Cache package (still stored locally at this point).

One thing I considered at this stage was adding an extension helper method to create a default Orleans IClusterClient instance. There’s at least 17 lines of setup-ceremony before you have an instance of IClusterClient that you can try connecting to the silo, but due to the Orleans architecture, this would have required the caching package to take a hard dependency on a specific clustering-persistence implementation. Without that helper it’s persistence-agnostic, so I left it as-is.

At this point I was back in business with release-version packages across the board.

Stateful Session Gone Wrong, Part 1

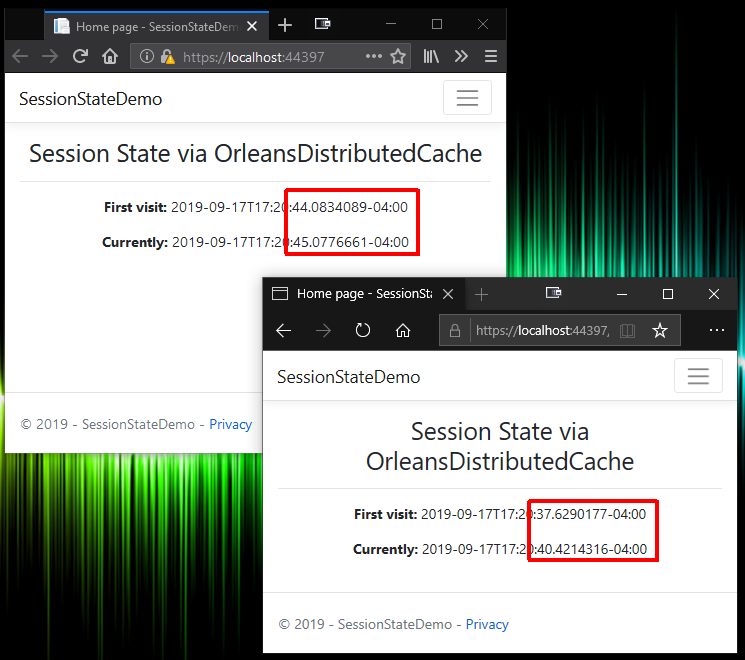

In the previous article, I demonstrated wiring up this caching system to ASP.NET Core’s stateful session support:

Imagine my disappointment when I ran the updated projects and realized the caching system wasn’t working! The demo is supposed to cache the first-load timestamp and refreshing the page shows that the first-load timestamp is retrieved from the cache. But now the first-load timestamp was changing on every reload. In the web app logs, I saw a pair of strange messages:

...DistributedSession: Accessing expired session, Key:xxxxxxxx

Followed by this message with the same key:

...DistributedSession: Session started; Key:xxxxxxxx

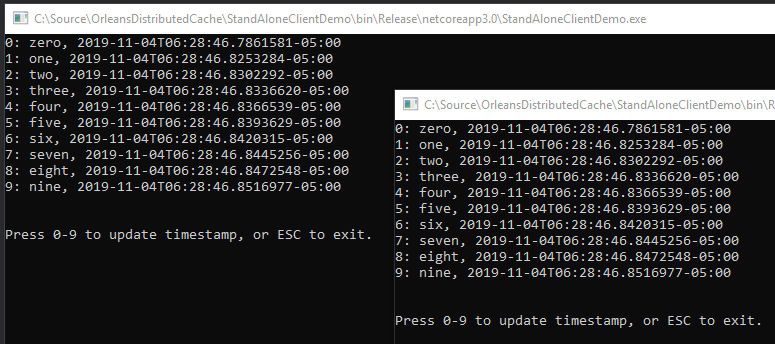

I knew for certain that the caching system itself was working outside the context of being driven by ASP.NET Core session. In the update process described in the previous section, I mentioned a “Stand Alone” demo project. It was in the repository for the previous article but wasn’t mentioned in that article. It’s a simple little console program that puts ten timestamps into the cache, and re-loads and displays them every 250ms, and updates them when you press a numeric key. If you run two of them side-by-side you’ll see the changes in one reflected in the other.

That Stand Alone test project is so simple, I had no doubts about the reliability of the cache itself.

Checking the browser F12 debug logs confirmed the correct session ID was being sent back and forth via cookie. I spent some time with Google looking for explanations. I found some session-related issues in older versions of ASP.NET Core that had been fixed. I also ran across this miniature bombshell about how Microsoft’s implementation of GDPR support could potentially render your session storage cookies inoperable. Fixing this had no impact, but I updated the ASP.NET Core demo to add the IsEssential flag to the session configuration:

1

2

3

4

5

services.AddSession(opt =>

{

opt.IdleTimeout = TimeSpan.FromMinutes(20);

opt.Cookie.IsEssential = true; // prevents GDPR changes from disabling session state

});

In the earlier article I described a bizarre quirk with Microsoft’s session implementation where cached state will only be loaded asynchronously if the developer laboriously calls HttpContext.Session.LoadAsync everywhere before referencing cached values. I was also aware that IDistributedSession exposes an IsAvailable property that reflects whether the session cache has already been loaded. Maybe I was supposed to check that first?

I added an IsAvailable check to the demo Index model:

1

2

if(!HttpContext.Session.IsAvailable)

await HttpContext.Session.LoadAsync();

Much to my surprise, this caused my cache service to throw the exception:

OrleansDistributedCacheService only supports asynchronous operations

Sync-Over-Async Hack

You may recall from the previous article that I decided to throw an exception instead of implementing the synchronous cache operations required by the interface. All of the Orleans storage operations are async, and sync-over-async is a Very Bad Idea. In fact, I was pretty surprised that Microsoft built the IDistributedCache interface to be primarily synchronous since it was new for .NET Core, and .NET Core makes heavy use of async Task patterns. I doubt anyone would have complained if it was fully async out of the box.

The bad part about sync-over-async is that there are ways to make it “mostly” work. Some of those tricks are worse than others. You should never do the popular .GetAwaiter().GetResult() hack, although I admit I’ve done it myself on demos and throw-away projects. One hack which apparently does work safely is to offload the work via TaskFactory so I created a private class inside the cache service class to handle this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

private static class SyncOverAsync

{

private static readonly TaskFactory factory

= new TaskFactory(CancellationToken.None,

TaskCreationOptions.None,

TaskContinuationOptions.None,

TaskScheduler.Default);

public static void Run(Func<Task> task)

=> factory.StartNew(task).Unwrap().GetAwaiter().GetResult();

public static T Run<T>(Func<Task<T>> task)

=> factory.StartNew(task).Unwrap().GetAwaiter().GetResult();

}

Usage is pretty simple. For example, executing Task<byte[]> GetAsync(string key) looks like this:

1

return SyncOverAsync.Run(() => GetAsync(key));

I bumped the cache project to version 1.0.2, updated all the demo project references, and tried again. While that allowed the program to check IsAvailable without blowing up, it didn’t fix my session caching problem. (I decided to leave the sync-over-async hack in the package, by the way, but the sync methods still have the Obsolete attribute on them to generate IDE and build warnings.)

At that point I did what I should have done earlier: I dug through the ASP.NET Core source (having the entire framework fully open sourced is still something of an amazing experience to me). It turns out that calling IsAvailable (source), which appears to be a simple Boolean property, has side-effects – another terrible design decision. Under the hood it calls a private synchronous Load operation (source), which in turn uses the cache’s synchronous Get method. That explained the exception, but more importantly, I didn’t see anything in that class which might account for the cache failures.

I was starting to get the feeling I was barking up the wrong tree by blaming ASP.NET Core.

Stateful Session Gone Wrong, Part 2

After a bunch of additional debugging, I discovered the real cause: my sample Orleans Silo project was configuring grain storage to serialize to the XML format. I showed this in the earlier article although I never got around to doing anything with the XML. In reality, when I tested session-based caching for the earlier article I hadn’t added the XML configuration line to the silo code yet – which is why session state caching worked when I took that screenshot for the article. (I’ve added updates to the earlier article so that people will be aware of these considerations.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

.AddAdoNetGrainStorage(

OrleansDistributedCacheService.OrleansDistributedCacheStorageProviderName,

opt =>

{

opt.ConnectionString = ConnectionString;

opt.Invariant = StorageProviderNamespace;

opt.UseXmlFormat = true; // the culprit!

})

I was momentarily puzzled by the fact that my working Stand Alone demo and my failing ASP.NET demo both stored DateTimeOffset objects in the cache, until I realized that ASP.NET actually stores a Dictionary of your session state data in the cache, and additionally that serialized dictionary is encrypted. Apparently one or both of those factors winds up being too much for Orlean’s XML serializer to cope with. The result is that the grain returns a null upon failure, and ASP.NET assumes nothing has been cached for that session yet, leading to the “expired session” message I saw in the logs.

Sure enough, removing UseXmlFormat from the Silo setup fixed the problem.

I tweaked a few more things here and there, bumped the cache project to 1.0.3, and pushed it out to GitHub and NuGet.

Stateful Session Gone Wrong, Part 3

When I wrote the previous article, I was on the fence about using tge obvious stateful sessions anti-pattern to demo the cache system. Now I definitely regret the decision, but that’s water under the bridge.

I strongly recommend against using the Orleans Distributed Cache for stateful ISession storage in ASP.NET web apps.

This doesn’t mean you should never use the package from web based apps – it only means you shouldn’t wire it up to session state.

Since we already fixed the bug, what is part 3 of the gone-wrong story?

Session state is widely considered an anti-pattern for web-based applications, but it is particularly bad with an Orleans-based cache. The Orleans part of this system persists cache entries by key, and session storage caches everything using the session ID as the key. Even if the cache entry is cleared (which ASP.NET does not guarantee since there is no standard mechanism for a browser to signal shutdown back to the server), “clearing” the state of an Orleans grain only persists a null value for that key (for performance reasons). This means you will have one row in your database for every session that has ever existed, unless you add a separate cleanup process (probably based on activity date, which Orleans also stores in the table).

The only thing worse than an anti-pattern that you don’t really need, is an anti-pattern that adds new undesirable side-effects.

ASP.NET itself doesn’t need session storage for anything, ever. Instead of using it, simply register and inject the Orleans Distribted Cache service directly (the extension method does this for you). Store values into the cache using unique keys based on concrete identifiers like the authenticated user ID, which might be an email address or some other Subject ID provided by an external Identity Provider login.

Conclusion

You can think of Orleans’ generic stateful grains as a type of distributed caching abstraction, although the actor model is more about behaviors than state. Building a well-known caching interface on top of that system is a pretty natural evolution of the model, and makes it easy to leverage Orleans’ clustering features for simple state storage requirements.

Comments