Learning to Program Part 1, Introduction

Introducing a beginner-level programming series.

In this introductory article, we’ll begin by learning about basic programming concepts without worrying about the details of any specific computer language.

There are many free websites and other resources online that will teach you how to program. When I began looking at them in detail, I was surprised that few of them present programming in a generalized way. This is a probably side effect of the modern era, where it can take considerable setup effort before you can start writing and running real programs. But the best developers don’t think in terms of programming languages. The language is a tool to get a job done. It’s true that when you’re writing programs for a living you tend to work with the same language (or a small handful) all the time, often for many years, but a good developer will generalize how they think about programming. Even hobbyist programmers usually learn many different programming languages (I had experience with about 15 languages before I got my first full-time programming job).

I have decided to write this series to explain programming to beginners, similar to the way I learned to program. In the late 1970s and early 1980s, Radio Shack published a series of soft-cover titles such as “Computer Programming in BASIC for Everyone” (which you can actually read online here). In those days they had to start with topics like, “How to recognize a computer” which takes three pages, but since you’re reading this with a browser here in the 21st century, I think we can skip forward quite a bit, although I’m still trying to assume the reader knows almost nothing technical beyond how to find these articles.

What is a Program?

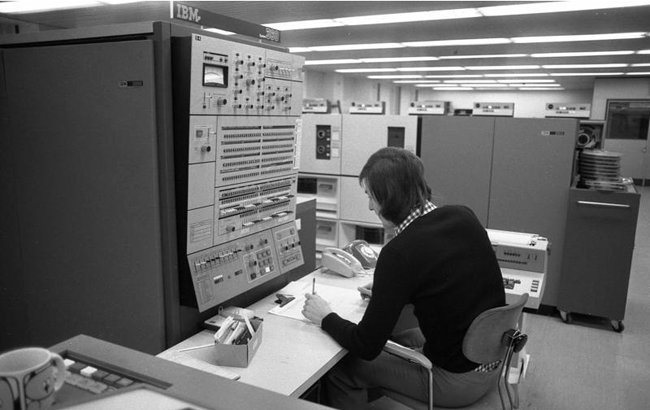

Even way back in the dark ages of the 1970s, most people could tell you that a computer program is a series of instructions that a computer uses to “do things.” Back then, people probably imagined a bunch of nerds standing around complicated-looking mainframe terminals in a brightly-lit college building, which was probably pretty close to the truth. In fact, we have photographic evidence. This guy must have been important because he had two telephones:

But if you want to write programs, saying they “do things” isn’t good enough. You have to ask yourself, how does a program work? Well, it runs on a computer, so it computes. Answers like these are like explaining how a car works by saying you put gas in the hole at one end, and that makes the car go. Learning to program is like learning to become an auto mechanic. You’ll need to know what happens between the hole where the gas goes and the wheels, and why that makes the car go. A mechanic must understand those concepts so that when the car doesn’t go, or they decide to build a car in their garage, they know how all the pieces work together, and why some pieces are needed in one place but not another. Earlier I said that good programmers don’t think about things in specific programming languages, which is similar to the way a good mechanic can work on different types and brands of cars. Mostly they work the same way, so a good mechanic starts by learning things that apply to all cars. That’s what we’re doing in these introductory articles.

One simple definition of a program is that it turns inputs into outputs. Imagine a programming language that uses nothing but basic arithmetic. A program could look like this:

1

1 + 2 = ?

In this “program” the numbers 1 and 2 are the inputs and ? is the output you want the program to determine (which is 3, obviously). But a computer doesn’t know what to do if you just throw numbers at it, programs also need commands that control what a computer does with inputs and outputs. Believe it or not, this “program” also has two commands. The plus-sign tells the computer to add the inputs, and the equal-sign tells the computer to output the result of adding them together.

Modern languages and libraries (I’ll explain libraries later) do a lot of things for you automatically, but you still have to tell a computer how to do almost everything when you write programs.

Of course, real computers do a lot more than simple math. Non-technical people often still believe that programming involves a lot of math, but that isn’t normally the case. Back in the computing dark ages, computers really did mostly just do math, but these days “inputs” involve things like the keyboard and mouse, touch screens, data stored on disk or the Internet, audio, and just about anything else you can imagine. Similarly, the commands used to process that data are also a lot more extensive than simple mathematical operations. We’ll get to all of that later. So if you don’t like math, don’t worry, most programming never involves anything more complicated than basic math. But if you do like math, you’re in luck, computers can do crazy-complicated math, although we aren’t going to cover any of that in this series.

Variables

At some point in everyone’s life, you are expected to learn algebra. When I learned to program, I was 8 years old and had probably never even heard the word. If you have learned algebra, you probably know what variables are. And even though I just wrote that programming rarely involves much math, it does rely very heavily on algebra’s concept of the variable. Just in case I have any readers who haven’t heard of algebra (or, like me, barely remember learning it), I’m going to explain what variables are. Skip ahead if you’re comfortable with the concept.

The simple math program shown earlier (1 + 2 = 3) isn’t very useful because it can only do one thing: add 1 and 2, and output 3. Specific values like 1, 2, and 3 are called literals. Variables give us a way to re-use those commands (the plus-sign and equal-sign) and the program’s logic with many different inputs and outputs instead of directly specifying literal values.

A variable is just a “bucket” that can store a value. When a programmer uses a variable in a program, the computer can use the value stored inside that bucket exactly as if the value itself was written directly into the program. Programs can take values out of a variable’s “bucket” but they can also put new variables into the “bucket” as well. The root-world of “variable” is “vary” and by definition. the value of a variable can change over time, as the program runs.

In the math world, a variable is usually just a letter, so we’ll change our program to use variables:

1

a + b = c

We’ve used a, b, and c as those variable “buckets” which can hold any number (notice we’ve also turned our ? placeholder into a variable). If we provide inputs by telling the computer that the a bucket contains the number 1, and the b bucket contains the number 2, the computer will put the number 3 into the c bucket. This is the variable-based version of the same thing we demonstrated earlier using the literal numbers 1 and 2, and always getting back 3. But since we’ve replaced specific numbers with variables that can hold any number, we can run our program with any two numeric inputs: assign 500 to a, and assign 250 to b, and when the computer processes our plus-sign and equal-sign commands, c becomes the total value, 750. You can see how this flexibility is very useful: one calculation program, many inputs and outputs.

Computer programs are literally just lots of and lots of variables, with various commands telling the computer what to do with all of those variables. A program does convert inputs to outputs, but more importantly it lets us re-use all of the commands in the program to process different inputs into different outputs.

In all modern computer languages, variables aren’t limited to single letters. Variables are normally full words or even short phrases which describe what their “bucket” is meant to hold. These more descriptive variables are called variable names. Using more detailed variable names helps programmers understand what the code is supposed to be doing. Let’s say we’re writing a shopping cart program. At checkout the total is the sum of the list price and the sales tax. Instead of having to remember that a is the price of something, and b is the sales tax, and c is the total cost, we can write our program using descriptive variable names:

1

listPrice + salesTax = totalCost

It’s exactly the same program, but now we know what it is meant to do, and it is easier to write.

In modern programming languages, variable “buckets” can hold more than numbers. For example, they can hold text, entire lists of values, references to other variables, and even small separate programs. Obviously these kinds of data aren’t used in mathetmatical calculations, but we will eventually cover all of these in later articles.

Variable Assignment

The concept of variable assignment answers the question, “How does the value 10 actually get stored into a variable bucket named listPrice?” In most programming languages, the equal-sign is used for assignment: storing values into a variable “bucket”.

First, we have to cover a minor technicality that applies to almost all programming languages. In a real programming language, our math program would almost always be written “backwards” compared to the “normal” way of writing a mathetmatical expression:

1

c = a + b

This “backwards” expression tells the computer, “set the value of variable c to the result of adding a and b”. This looks weird compared to normal math, but it’s this way mainly for historical reasons: it was easier for older computers to understand the program if written this way.

More importantly, it’s also easier for a programmer to read. In a real program you’re usually more interested in where the results are stored than in the details of how the program produces those results, so it’s natural for the target variable to show up first in the code.

As you have probably guessed, we also use that syntax to assign values to any variable, not just the result of calculations:

1

2

3

a = 1

b = 2

c = a + b

And suddenly, we have a real multi-line program with variable inputs – one of the most important core concepts of all modern programming. It reads the same way we just described for the one-line example:

- set the value of variable

ato the value ‘1’ - set the value of variable

bto the value ‘2’ - set the value of variable

cto variableaplus variableb

Written more realistically with full variable names, our program becomes:

1

2

3

listPrice = 10.00

salesTax = listPrice * 0.07

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

Notice the calculation in the second line. In most languages the asterisk * symbol is used to multiply numeric values, because the x symbol that everyone learns in school could be mistaken for a variable name. Also notice the calculation mixes the use of a variable and a numeric literal. In most places in a program, anywhere you can use a literal value, you can also use a variable, and vice-versa.

In math terminology, symbols like a multiply-sign or a plus-sign are called “operators” and in programming terminology the equal-sign is usually called the assignment operator.

Other Commands

Most programming languages consist of many different commands, most of which are used to interact with variables. In the next installment of this series, we’ll talk about common types of commands, but for now we’ll continue working with our simple made-up example to explore the kinds of things commands allow us to do.

In the previous section, we have the same problem we had in the original version of our program, 1 + 2 = 3, because literal numeric values are used. We’ve just moved the numeric values into variables, but they’re still literal numbers in the code – they can’t change. Another problem is that we don’t have a way to see the program output. We store it into the variable c but variable “buckets” are just a spot somewhere inside the computer’s memory.

Let’s pretend our language has two more commands. The command called input retrieves a user’s keystrokes, and the command called print shows the value stored in a variable’s bucket on the screen. (Many languages have a “print” command for historic reasons, dating back to the mainframe era when computers really did physically output results on paper using a printer – before screens were used at all. Notice in the mainframe picture at the start of the article there aren’t any screens, only a paper-output terminal over by Mr. Important’s two telephones.)

Now our program looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

print "Enter the price:"

listPrice = input

salesTax = listPrice * 0.07

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

print "Please pay:"

print totalCost

Earlier we mentioned variables can hold text, and you’ve already seen that variables and literals are usually interchangeable. We said that our print command shows the value of a variable, but here our first line specifies a text literal instead: the words Enter the price. In most languages, text literals are called strings and they are usually surrounded by quotation marks to help the computer figure out where the string starts and stops. So the first line of this program displays Enter the price: on the screen before it gets to the second line which says, “set the variable listPrice to the value the user typed on the keyboard”.

If you run this program, the user is asked for the price. If you type 10 as the input price, that gets stored to the listPrice variable and the third line calculates a 7% sales tax of 70 cents. Finally we calculate totalCost as 10.70 by adding the two numbers, we print another string literal to label the output, and we end by outputting the result of our calculations to the screen. The on-screen result would look like this:

1

2

3

4

Enter the price:

10

Please pay:

10.70

Functions

This next bit is as deep as the math gets in this series, and it’s really just background information:

Before there was programming, mathematicians understood the value of re-use. Even though most programmers never do any complicated math, computers and the first programming languages were invented by scientists, so they borrow a lot of concepts from math, such as variables. Another of those concepts is the function. In math, you might define a function using an expression like this:

f(x) = x + 1

In this case x becomes a placeholder (called an argument) for some other value, which can be replaced by a literal or a variable. This means, “x is some unknown value, and when somebody writes f(x) in their equation, add 1 to whatever x is” – so the value f(2) is 3 – we say the function f(2) returns the value 3. In other words, writing f(2) in an equation is the same as writing a literal 3 in the equation. As we saw while learning about variables, literals aren’t too useful when used that way: why bother with f(2) instead of cutting out the middleman and writing 3 directly? The real value of a function is when you can define f(x) as shown, but later then replace the argument x with another variable, such as f(a). If the value of a is 100, then f(a) returns 101 using the function defined above.

Math lesson over.

I mention all of that because most real programming languages are full of functions, and they follow that same general f(x) formatting. Luckily, like variables, we give them better names than “f”. In fact, input and print from our imaginary programming language would be examples of functions. Some functions like input don’t need any arguments, but we still use a set of parenthesis to identify them as functions. Other functions like print do require an argument, and some functions can take many arguments. Let’s clean up our program a little bit by adding parenthesis to our functions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

print("Enter the price:")

listPrice = input()

salesTax = listPrice * 0.07

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

print("Please pay:")

print(totalCost)

The example above demonstrates something about functions in the world of programming. In the math world, functions always return a value – that’s their whole point. In programming, functions “do stuff” which may include returning a value. In this simple example, the input() function returns whatever the user has typed. But the print(text) function doesn’t return anything, it just outputs the value of the text argument to the screen.

Functions in the mathetmatical sense are usually just one equation, but it’s important to understand that programming functions are small programs in their own right. In other words, the input and print functions are each made up from more programming code. Even though the text part of print(text) is the argument to the print function, inside the code that makes print do what it does, the text argument is used just like any other variable. We call it an argument instead of a variable to make it clear that it is input to a function.

This, too, is a core programming concept – we can re-use code by packaging it up inside functions that are easy to refer to by name. Most programs are just a series of functions that call each other to do work on variables. You can think of functions as a type of command (and in fact, with only a few low-level exceptions, most programming languages are built exactly that way).

Custom Functions

Since functions are so important, nearly all languages let you define your own functions. We’re reaching the point where our pretend-language is not useful, but let’s imagine you can do something like this to define a custom function, where you’d replace fn with your custom function name and arg with your function’s argument name, and the “…” represents the area where you add custom programming commands (the work performed by the function), and return is where your function definition stops, optionally returning the value of a variable used inside the function:

1

2

3

function fn(arg)

...

return

A simple function could look like this:

1

2

3

4

function CalculateTotal(price)

tax = price * 0.07

cost = price + tax

return cost

You can see we’re performing the same operations shown in our earlier examples, but now it is encapsulated inside a re-usable function named CalculateTotal. This means we can use that same logic over and over again throughout the program, without having to write those calculations out each time. Another important concept shown here is that variables inside a function aren’t normally accessible outside the function. Neither tax nor cost have any meaning outside of this function. Using them in the “outer” code would cause an error. Similarly, code inside a function normally can’t use variables outside the function. The function returns the value of the variable cost when it ends. The code using this function would store this return value somewhere in a variable known to the “outer” code.

We would use it in our program to replace our own calculations as shown below. Using a function from the “outer” code like this is known as a function call:

1

2

3

4

5

print("Enter the price:")

listPrice = input()

totalCost = CalculateTotal(listPrice)

print("Please pay:")

print(totalCost)

Here in the “outer” code our price is stored in the variable listPrice, which we pass into the CalculateTotal function as an argument. Inside that function, the same value is represented by the price argument, which is used just like any other variable inside the function. The function’s return value is assigned to the “outer” code’s totalCost variable. Remember, this outer code (usually referred to as the caller) can’t see the variables tax and cost inside the function – it only sees the return value, the actual numeric value that was calculated and stored in the cost variable while the code inside CalculateTotal was still running.

Conclusion

Although these examples use a simple, imaginary language, they cover most of the important core ideas that all programmers use every single day. Next time we’ll talk about slightly more complicated concepts that are also fundamental parts of writing software in any language.

Part 2: Data Types and Debugging

Comments