Securing Orleans Microservices with OpenID Connect

Validating JWT access tokens using an Orleans filter.

I’ve written before about the Microsoft Orleans platform, which I’ve found to be a great microservices hosting model. One shortcoming of the platform is that it’s completely unsecured. Part of the popular OpenID Connect (OIDC) specification includes service-layer security in the form of “access tokens” stored in the JWT (JSON Web Token) format. I’ve recently written about how to obtain and manage those with Blazor server-side applications (and there is more to come, on that subject) but today we’re going to look at how to use them in an Orleans-hosted API.

To quickly recap, in Orleans terminology a host is a “silo” and the various services it can host are “grains”. We’ll build a simple ASP.NET Core MVC site that can authenticate against an OIDC authority (specifically, the publicly available IdentityServer4 demo authority), a sample secured service in the form of a grain that can add two integers, and a different Orleans component called a filter which performs the access token validation process.

Code for this article is in my repository: MV10/OrleansJWT. It is based on ASP.NET Core 3.1 and Microsoft Orleans 3.0.

App Program Main

The App project began as a new copy of the ASP.NET Core “Web Application” template without Identity support (which I’ve ranted about before, so I’ll spare you now). In Program.cs I haven’t been a fan of the strange pattern Microsoft follows with the separate CreateHostBuilder method, rather than dumping those few lines into Main. It turns out that’s yet another of those poorly-documented “conventions”, apparently needed by Entity Framework. So there are probably millions of non-EF applications out there blindly following this pattern without the slightest need or idea why… Anyway, we do away with that, moving our startup process into Main.

We don’t need anything special for the ASP.NET Core side of the house, but we’re also going to host the Orleans silo under the same Generic Host process, so that requires adding a few NuGet packages. We need just one, the 3.0 release of Microsoft.Orleans.Server, then we can write our bare-bones Main method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

public static async Task Main(string[] args)

{

var host = Host.CreateDefaultBuilder(args);

host.UseOrleans(builder =>

{

builder

.UseLocalhostClustering()

.Configure<EndpointOptions>(options => options.AdvertisedIPAddress = IPAddress.Loopback)

.AddIncomingGrainCallFilter<AccessTokenValidationFilter>()

.ConfigureApplicationParts(parts =>

{

parts.AddApplicationPart(

typeof(SecureAdderGrain).Assembly)

.WithReferences();

});

});

host.ConfigureWebHostDefaults(webBuilder =>

{

webBuilder.UseStartup<Startup>();

});

await host.RunConsoleAsync();

}

We’ll talk about the SecureAdderGrain and the AccessTokenValidationFilter a bit later.

App Startup

Over in the Startup.cs file we only need two simple additions for OIDC support. Again, this authenticates against the publicly-accessible IdentityServer4 demo server, which allows you to login using your federated Google identity, or using the locally-defined (local to the demo server) user/password combos “bob/bob” or “alice/alice”. I chose to use one of the interactive login client IDs so that it would be easier to show what happens when the user calls the service when they aren’t authenticated, but it would be easy to configure this same demo for the machine-to-machine (m2m) non-interactive API-only authentication, also available with the same demo server.

Add this code to the end of ConfigureServices:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

services.AddAuthentication(options =>

{

options.DefaultScheme = "Cookies";

options.DefaultChallengeScheme = "oidc";

})

.AddCookie("Cookies")

.AddOpenIdConnect("oidc", options =>

{

options.Authority = "https://demo.identityserver.io/";

options.ClientId = "interactive.confidential";

options.ClientSecret = "secret";

options.ResponseType = "code";

options.SaveTokens = true;

options.GetClaimsFromUserInfoEndpoint = true;

options.Scope.Add("openid");

options.Scope.Add("api");

options.Scope.Add("offline_access");

});

Also add authentication support to Configure:

1

2

3

app.UseRouting();

app.UseAuthentication(); // add this

app.UseAuthorization();

These additions are pretty standard for OIDC-secured apps, so I won’t spend time going over them. Several of my recent articles do discuss some aspects of these options if you wish to read more about it. Next we’ll make a couple quick changes to provide basic login/logout capabilities.

App Index Page

At the top of Index.cshtml we add support for an optional handler argument, the MVC Razor convention for route-based mapping to page model methods like OnGet[handler] and OnPost[handler]:

1

@page "/{handler?}"

Then at the end of the page we’ll add links to perform a login or logout, and to execute the API call we’ll build later:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

<p>

@if (User.Identity.IsAuthenticated)

{

<a class="btn btn-outline-primary" href="/Logout">Logout</a>

}

else

{

<a class="btn btn-outline-primary" href="/Login">Login</a>

}

<a class="btn btn-outline-primary" href="/CallAPI">Call API</a>

</p>

<p>

UTC now:<br />

@DateTimeOffset.UtcNow

</p>

<p>

Login UTC expiration:<br/>

@Model.LoginExpiration

</p>

Now jump to the page model code in Index.cshtml.cs and change the code as shown:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

public string LoginExpiration;

public string FilterResult;

public string ApiResult;

public async Task OnGet()

{

ApiResult = "(click Call API button)";

FilterResult = ApiResult;

LoginExpiration =

await HttpContext.GetTokenAsync("expires_at")

?? "(no expiration claim)";

}

public IActionResult OnGetLogin()

{

var authProps = new AuthenticationProperties

{

IsPersistent = true,

ExpiresUtc = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow.AddHours(15),

RedirectUri = Url.Content("~/")

};

return Challenge(authProps, "oidc");

}

public async Task OnGetLogout()

{

var authProps = new AuthenticationProperties

{

RedirectUri = Url.Content("~/")

};

await HttpContext.SignOutAsync("Cookies");

await HttpContext.SignOutAsync("oidc", authProps);

}

Specifying the IdentityServer demo-specific api scope and the OIDC-defined offline_access scope is critical here – that’s how you obtain the access token we need to call the secured service. It also returns a refresh token, but refreshing the access token is outside the scope of this article.

There isn’t much else to say about this, it’s pretty self-explanatory and I’ve written about it many times before. If you temporarily disabled the Orleans silo startup (since we haven’t yet seen the grain and filter classes it needs), at this point you could run the project and perform a login/logout, but that’s it. We’ll come back to the Index page later to actually execute the API call and show the results.

SecuredGrain Project

A .NET Standard 2.0 library is home to our service grain and the token validation filter (normally they’d be separate libraries since filters are usually intended to be widely reusable). The project requires several NuGet packages. It’s easiest to just double-click the project name in Solution Explorer and paste this into the csproj file directly:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<ItemGroup>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Orleans.Client" Version="3.0.0" />

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Orleans.CodeGenerator.MSBuild" Version="3.0.0">

<PrivateAssets>all</PrivateAssets>

<IncludeAssets>runtime; build; native; contentfiles; analyzers; buildtransitive</IncludeAssets>

</PackageReference>

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Orleans.Core.Abstractions" Version="3.0.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.IdentityModel.Tokens.Jwt" Version="5.6.0" />

</ItemGroup>

API Response Wrapper

When you build a remotely-accessible service, it’s best to return more than the raw results expected from the call itself. For example, HTTP isn’t well-suited to propagation of .NET-style exception information, so you should at least support an indication of success or failure alongside your return value. Also, the specifics of your user base and application will dictate how much information you return about a failure, for the same reason a production ASP.NET site typically disables stack trace dumps on error message pages.

For this project, we’re creating an Orleans filter to secure our service calls, so we’ll wrap the service call return data in a SecuredResponse object. This requires a generic <TResult> argument tho define the service call’s return data type, provided in a Result property. It implements an interface called ISecuredResponseValidation with just two properties, Success and Message. The rationale for the interface will become clear later.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public interface ISecuredResponseValidation

{

bool Success { get; set; }

string Message { get; set; }

}

public class SecuredResponse<TResult>

: ISecuredResponseValidation

{

public TResult Result { get; set; }

public bool Success { get; set; }

public string Message { get; set; } = string.Empty;

}

We’ll explain how and why later, but simply returning Task<SecuredResponse<T>> is all a grain method must do in order to be secured by the validation filter. No extra declarations, attributes, configuration, or other wiring-up is required.

API Service Grain

The SecureAdderGrain is a very simple service which simply adds two numbers. We define it as an Orleans [StatelessWorker] because we don’t care about state and we don’t have a reason to do anything special with grain keys for this demo.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

public interface ISecureAdderGrain

: IGrainWithIntegerKey

{

Task<SecuredResponse<int>> Add(int value1, int value2);

}

[StatelessWorker]

public class SecureAdderGrain

: Grain, ISecureAdderGrain

{

public Task<SecuredResponse<int>> Add(int value1, int value2)

=> Task.FromResult(new SecuredResponse<int>

{

Result = value1 + value2

});

}

As promised, notice the grain doesn’t do anything related to exception handling, nor does it do anything security-related apart from wrapping the return data in our SecuredResponse class.

Calling the API

Now we can go back to the Index page and update it to execute an API call. Add these two lines to the end of Index.cshtml to output the results of our call:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

<p>

API call result:<br/>

@Model.ApiResult

</p>

<p>

Filter result:<br/>

@Model.FilterResult

</p>

Then in the Index.cshtml.cs page model, we’ll implement the handler to make the API call:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

private readonly Random random = new Random();

private readonly IClusterClient clusterClient;

public IndexModel(IClusterClient clusterClient)

{

this.clusterClient = clusterClient;

}

public async Task OnGetCallAPI()

{

var accessToken = await HttpContext.GetTokenAsync("access_token");

RequestContext.Set("Bearer", accessToken);

var adder = clusterClient.GetGrain<ISecureAdderGrain>(0);

int v1 = random.Next(1, 100);

int v2 = random.Next(1, 100);

var result = await adder.Add(v1, v2);

ApiResult = result.Success

? $"Add({v1}, {v2}) = {result.Result}"

: "(unsuccessful)";

FilterResult = result.Message ?? "(no message)";

}

This is pretty self-explanatory. We inject the Orleans cluster client (silo-startup registers it automatically) and we create a new random number generator.

During the API call handler, we get the OIDC access token from the ASP.NET Core-managed authentication cookie, and we use the special Orleans static class RequestContext to store it as a bearer token. The contents of that class will be serialized with every call, so in a real project this could actually be set once after login, and updated whenever a refresh token was used to update the access token.

We generate two random numbers, we await the API call, and we output the results. Very simple.

If you run the project now, the API call works regardless of whether you’re logged in, or even if you’re logged in but the access token has expired.

Validating the Access Token

The Orleans documentation uses the term “filter” and “interceptor” interchangeably, which is a little confusing at first. I decided to stick with the term “filter” since that’s what all the intefaces, classes, and methods use in the real code.

The filter must implement just one method with this signature:

1

public async Task Invoke(IIncomingGrainCallContext context)

Filters are pretty simple to understand – Orleans is a messaging-driven remote-method-invocation system, so a filter receives a message before the grain receives it. The filter decides when (or if) the grain actually receives the message. The filter is called with a context object which exposes everything about the call in properties using standard reflection-style types like MethodInfo. Crucially, there is also a Response property which contains the result of executing the grain call, and the filter is free to read or write to this property both before and after grain invocation.

It’s important to remember that Orleans itself uses the same messaging infrastructure for things like silo-to-silo cluster management, so you can’t blindly apply your logic to every call which hits the filter. Because of this, I’m a little surprised Orleans doesn’t have a standardized way to differentiate between your own messages versus internal messages.

We could naively check whether the targeted grain is our sample class with a line like this:

1

2

3

4

if(context.Grain is SecureAdderGrain)

{

// etc.

}

However, that isn’t very flexible. Since we know all secured services return a SecuredResponse object, it’s better to inspect the ReturnType property of the method being called. At first I thought I could test whether the return data implements the ISecuredResponseValidation because an interface-check is fast and easy. That’s when I bumped into the fact that the filter will also see Orleans’ internal message traffic.

Since Orleans absolutely requires wrapping all calls in a Task, the ReturnType is always a Task of some kind, and it turns out many of the internal message Task returns are non-generic. At that point checking for the interface became more complicated than looking for the SecuredResponse<> open generic type.

I wrote a simple type-checking method local to the Invoke method so that it could capture the context argument. It returns either a reference to the full SecuredResponse<TResult> type defined inside the Task<T> method return type, or a null if any of the conditions fail before it can find our supported type. We call that method as the first step in the filter’s Invoke implementation:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

public async Task Invoke(IIncomingGrainCallContext context)

{

var securedResponseType = GetSecuredResponseType();

if(securedResponseType == null)

{

await context.Invoke();

return;

}

// TODO - process a secured grain

// captures the Invoke method's context argument:

Type GetSecuredResponseType()

{

var task = context.ImplementationMethod.ReturnType;

if (!task.IsGenericType) return null;

if (!task.GetGenericTypeDefinition().Equals(typeof(Task<>))) return null;

var taskArg = task.GetGenericArguments()[0];

if (!taskArg.IsGenericType) return null;

if (!taskArg.GetGenericTypeDefinition().Equals(typeof(SecuredResponse<>))) return null;

return taskArg;

}

}

Note that we assume the grain doesn’t do anything weird with our SecuredResponse class, such as Task<string, SecuredResponse<int>> – that won’t be recognized and the call will be processed without any access token validation.

If we don’t get back a type describing a SecuredResponse we simply invoke the target and bail out – the filter isn’t being executed for a secured service. However, if we do get something back from GetSecuredResponseType, it’s time to validate the access token.

First, we’ll add another local method:

1

2

3

4

5

void SetSecuredResponse(bool success, string message)

{

((ISecuredResponseValidation)context.Result).Success = success;

((ISecuredResponseValidation)context.Result).Message = message;

}

This is where the ISecuredResponseValidation interface comes in handy. The context.Result property is just an object which must be cast to something else to make it useful. However, our grain method returns a SecuredResponse<TResult> type, and we can’t know in advance what <TResult> will be, so it’s impossible to perform a cast or conversion. But we only need part of the response, which is exactly what interfaces are for.

The TODO comment in the earlier code is replaced by this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

try

{

var accessToken = (string)RequestContext.Get("Bearer");

if (string.IsNullOrWhiteSpace(accessToken))

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (bearer token missing in RequestContext)");

await ThrowIfTokenInvalid(accessToken);

await context.Invoke();

SetSecuredResponse(true, "Authorized");

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

context.Result = Activator.CreateInstance(securedResponseType);

SetSecuredResponse(false, $"{ex.GetType().Name}: {ex.Message}");

}

We retrieve the access token from the Bearer-keyed entry of Orleans’ RequestContext static dictionary, and we confirm that some value was actually provided. Next, we call a new method, ThrowIfTokenInvalid which does nothing if the access token passes all validation checks, or throws an exception if a problem is found.

Finally, we invoke the target grain method, and as long as no exception was thrown, we assume success and return the filter-result message of “Authorized”.

The catch block is the reason our local GetSecuredResponseType method returns a type instead of a boolean: when something goes wrong, context.Result will still be null. We need a way to create a new SecuredResponse<TResult> so that we can set the Success and Message properties in the event of an exception.

JWT Validation Process

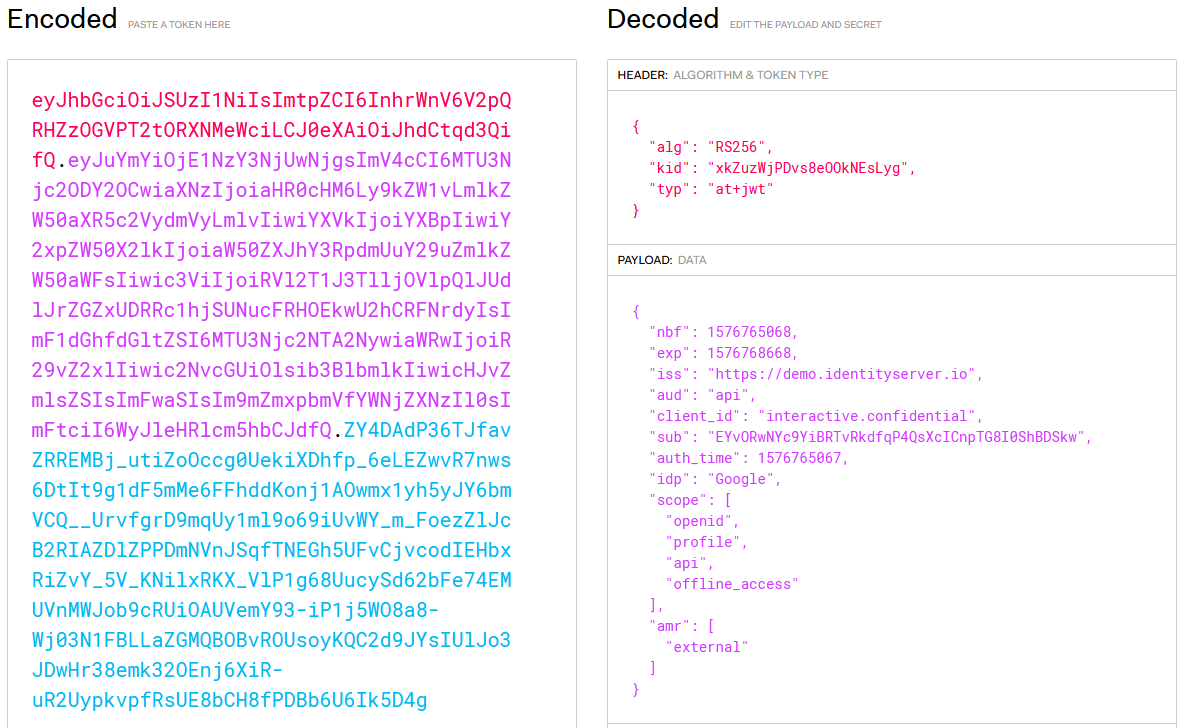

A JWT is just an encoded JSON data object. It isn’t necessarily encrypted, and even encrypted tokens are easily decrypted with publicly-available keys. Consequently you can paste it somewhere like JWT.io to view the contents (although you shouldn’t do this with tokens issued for anything important, as you’re literally giving away data that can be used to execute service calls). When we put one of the IdentityServer demo server tokens into JWT.io, we find something that looks like this:

This makes it easy to use a JWT on the server side, but it also means a JWT by itself can’t be trusted because anyone can easily generate a JWT that is formatted correctly. You have to confirm that the token was really issued by an authority. There are several ways to do this and I will link to additional information later. This example illustrates one approach: OIDC defines a “token introspection endpoint” for authority servers that you can pass a token into and get back information about the token. During that process the authority validates the token, which tells you that you can trust it (with the implied assumption that you trust the authority itself; there is no security value in contacting an authority you don’t recognize).

Because network calls have a lot of overhead, you should cache a validated token so that you can recognize it on subsequent calls without another network call to the authority server. You can check for expiration without a round-trip, and there are other claims on the token that you can verify locally.

These are the steps we’ll implement to validate access tokens (in this order):

- Is it a real token?

- Has the token already expired?

- Does the token apply to the correct scope, called an Audience?

- Is this really an access token (and not, for example, a refresh token)?

- If any of the above are false, remove the token from cache, if applicable.

- If the above were passed and the token is in the cache, allow it to be used.

- If the token is new (not in the cache), validate with the authority server.

- Check whether the authority server has revoked the token.

- Cache the token for later calls.

There is a minor loophole here. After you cache the token, you will no longer be aware of token revocation before the token expires, since you can only discover revocation by contacting the token authority again. Revocation virtually never happens, though, so this risk is minor compared to the elimination of network traffic to validate a token on every API call.

How you cache the tokens is an implementation detail. Access tokens have relatively short lifespans (typically an hour or two), so ideally choose a caching system that can auto-expire cache entries based on time.

JWT Validation Code

Since we have to contact the OIDC authority, we’ll need a few more packages and some extra setup code. We add four new packages to the Orleans grain project:

1

2

3

4

<PackageReference Include="IdentityModel" Version="4.1.1" />

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Extensions.Caching.Abstractions" Version="3.1.0" />

<PackageReference Include="Microsoft.Extensions.Http" Version="3.1.0" />

<PackageReference Include="System.IdentityModel.Tokens.Jwt" Version="5.6.0" />

The web app only needs one additional package:

1

<PackageReference Include="IdentityModel" Version="4.1.1" />

Then in the ConfigureServices method of Startup.cs in the web app, we need to register a few additional services for injection. We’re using the ASP.NET Core IMemoryCache because we don’t need persistence or features like sharing our cache across multiple servers – it’s relatively minor overhead to have each server in a cluster validates the same token.

Once again, your specific implementation needs should dictate how you set up the cache. For this simple example, we’re foregoing real-world considerations like cache entry expiration and settings to limit the size of the cache. As shown below, this cache would simply grow forever, as long as the server remained up and ready.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

services.AddMemoryCache(); // NOT PRODUCTION-FRIENDLY (needs configuration)

services.AddHttpClient();

services.AddSingleton<IDiscoveryCache>(sp =>

{

var factory = sp.GetRequiredService<IHttpClientFactory>();

return new DiscoveryCache(

"https://demo.identityserver.io",

() => factory.CreateClient());

});

Back in the AccessTokenValidationFilter class, we need to inject those same services by adding these fields and a constructor:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

private readonly IMemoryCache memoryCache;

private readonly IDiscoveryCache discoveryCache;

private readonly IHttpClientFactory httpClientFactory;

public AccessTokenValidationFilter(

IMemoryCache memoryCache,

IDiscoveryCache discoveryCache,

IHttpClientFactory httpClientFactory)

{

this.memoryCache = memoryCache;

this.discoveryCache = discoveryCache;

this.httpClientFactory = httpClientFactory;

}

We add a one-liner method to produce our standardized cache key. Bear in mind the cache is system-wide, so you’ll want to generate keys that won’t collide with other possible uses of the cache. Here we’re using the subject ID (how the authority identifies the logged-in identity) prefixed by the text accesstokensid: which should be pretty unique:

1

2

private string GetCacheKey(JwtSecurityToken jwt)

=> $"accesstokensid:{jwt.Subject}";

Now we can implement the validation logic. Recall that the filter’s Invoke method executes something called ThrowIfTokenInvalid. That method looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

private async Task ThrowIfTokenInvalid(string accessToken)

{

var handler = new JwtSecurityTokenHandler();

var jwt = handler.ReadToken(accessToken) as JwtSecurityToken;

try

{

if (jwt.ValidTo <= DateTime.Now)

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (token expired)");

if (!jwt.Audiences.Any(a => a.Equals("api")))

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (api scope required)");

if (!jwt.Header.ContainsKey("typ")

|| !jwt.Header["typ"].Equals("at+jwt"))

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (wrong token type)");

}

catch

{

var key = GetCacheKey(jwt);

memoryCache.Remove(key);

throw;

}

if (!IsKnownToken(jwt))

await VerifyAndCacheToken(jwt);

}

The JwtSecurityTokenHandler object has a variety of other methods you might wish to review, such as validating that the token format is correct. Oddly, that is only documented in relation to Azure even though it comes from a NuGet package that has no obvious Azure references. Even more oddly, the ReadToken method actually returns a SecurityToken object, which is a very limited class. The docs and the Intellisense summary claims it returns the more complete JwtSecurityToken object. It does not, but it can be cast to one.

Once we have our decoded JWT, we can apply our validation tests. The first three can be run locally before we ever try contacting the authority: has it already expired, does it apply to the correct scope (scope is an OIDC term, audience is the JWT equivalent), and is it the correct type (an access token)?

If any of those fail, we throw an exception. The catch block will remove the token if it was previously cached, then re-throws the exception so that our Invoke method will return the failure to the client.

If those succeed, we test whether the token has been cached on some previous call. If so, we consider the token valid and exit. The cache-check is implemented by IsKnownToken:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

private bool IsKnownToken(JwtSecurityToken jwt)

{

var key = GetCacheKey(jwt);

if (!memoryCache.TryGetValue(key, out var cachedValue)) return false;

if (!cachedValue.Equals(jwt.RawData))

{

memoryCache.Remove(key);

return false;

}

return true;

}

It’s a pretty simple piece of code. The value stored in the cache is the token itself. In theory we could improve security by hashing the token before storing it, but if an attacker has access to run code to expose values in of your web server’s in-memory cache, you have bigger problems than API access token leakage to worry about.

If the key (the user’s subject ID) is found but the token doesn’t match, it’s an old token, so we remove it from the cache.

If the token is not in the cache, this means we haven’t seen it before and we should proceed with back-channel authentication (that is, contacting the OIDC authority to verify the authenticity of the token). That happens in the VerifyAndCacheToken method:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

private async Task VerifyAndCacheToken(JwtSecurityToken jwt)

{

var discovery = await discoveryCache.GetAsync();

if (discovery.IsError)

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (authority discovery failed)");

var client = httpClientFactory.CreateClient();

// this user/pass combo is specific to the IdentityServer demo authority,

// and the use of scope as the username is generally specific to IdentityServer

client.SetBasicAuthenticationOAuth("api", "secret");

var tokenResponse = await client.IntrospectTokenAsync(

new TokenIntrospectionRequest

{

Address = discovery.IntrospectionEndpoint,

ClientId = "interactive.confidential",

ClientSecret = "secret",

Token = jwt.RawData

});

if (tokenResponse.IsError)

throw new Exception($"Unauthorized (introspection error: {tokenResponse.Error})");

if (!tokenResponse.IsActive)

throw new Exception("Unauthorized (token deactivated by authority)");

var key = GetCacheKey(jwt);

memoryCache.Set(key, jwt.RawData);

}

The IdentityModel helper-class IDiscoveryCache is used to locate “well-known endpoints” of an OIDC server. In our case we need the “token introspection” endpoint. Before we can call that, we have to set a Basic Authentication header on the HttpClient object. This is recommended by the OIDC specification, although the spec doesn’t require a specific implementation. The spec illustrates using the OIDC client ID and client secret as the username and password, but IdentityServer expects the requested scope and client secret (and annoyingly, the Identity Server docs don’t mention that fact anywhere that I could find, which wasted about three hours of my life). The call to SetBasicAuthenticationOAuth is a helper-extension which also comes from the IdentityModel package.

We prepare a few arguments that are passed to the introspection endpoint, and we check the response for success. Finally, we call IsActive to confirm that the token was not revoked, then we cache the result and exit.

From that point the token has been validated and the API call is executed. The Invoke method updates the SecuredResponse properties to indicate success, and everything flows back to the client.

Test Run

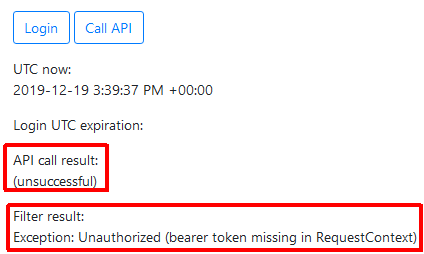

And just to show that it works – if you aren’t logged in and try to execute the API call, you’ll see this:

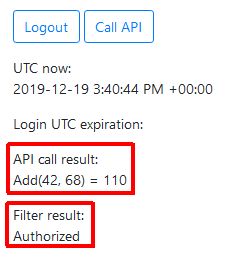

After logging in, all the validation tests succeed and the secured grain service adds the two random numbers sent by the client:

Conclusion

Note there are many other options and processes to validate the contents of a JWT. Most for-pay authorities such as Auth0, Okta, or connect2id have guides and blog posts about it (with varying dependencies on the specifics of their tokens and/or frameworks and libraries) which are worth reviewing.

Microsoft Orleans hasn’t (yet) taken the microservices world by storm, but I hope this relatively simple example helps demonstrate just how capable and easy-to-use that platform is.

Comments