System Tray Icons with WPF in the .NET Core 3.0 Preview

WPF support in .NET Core 3.0 Preview 1 is remarkably complete.

When .NET Core 2.0 finally arrived, I completely wrote off the .NET Framework. It bothered me there wasn’t a good way to write native Windows applications in .NET Core, but given the massive resources Microsoft was pouring into .NET Core, I figured that situation wouldn’t last long. Just one year later my suspicions were proven correct: in May 2018, Microsoft announced that an optional SDK for .NET Core 3.0 will add support for Windows desktop applications based upon either the positively ancient WinForms model or the WPF/XAML model. The Preview 1 release has been out for a couple of months, so I thought I’d take it for a spin.

Last year I was thinking about a little utility I’d like to write which would live in the System Tray. That utility isn’t important to the article, but after a few days of messing around with the idea in .NET Core 2.x, I realized it was never going to happen. I was rapidly digging deeper and deeper into the Win32 API DLLs and at that point I might as well either go back to the .NET Framework or dust off my C compiler. Recently I realized the new WPF preview might have what I need.

Speaking of the System Tray, I can’t quite figure out what Microsoft calls that part of the Task Bar these days. It sort of seems to go by the name Notification Area, but I thought that also applied to the big vertical bar where Windows dumps pop-up messages and annoying advertisements for OneDrive. I’m sticking with System Tray.

WinForms has System Tray icon support built right in, but WPF never has. Developers have asked for this for about ten years, but Microsoft’s position was that the System Tray is an OS feature, whereas WPF is presentation-focused. I’m not sure I understand the distinction, but fast forward to 2019 and this stance is pretty ironic given that Microsoft now says they won’t make WPF cross-platform because… it’s too tightly tied to Windows. If Microsoft can have their cake and eat it too, maybe we’ll get System Tray support in WPF some day, too.

The WPF NotifyIcon Library

Most of the WPF tray icon examples out there pull in the WinForm assemblies. I was planning to go the Win32 API route when I stumbled across a cool little library from Philipp Sumi called WPF NotifyIcon – or possibly the other way around, his BitBucket repo and the project name is NotifyIconWPF. Regardless, it has a ton of features and works well. I cloned his code and got to work. No point in reinventing the wheel.

Much to my surprise, it was easy to get the library and his sample code running under .NET Core 3.0. There were zero changes required to the C# or XAML. Getting it working was strictly a matter of setting up the projects correctly, and that’s what this article is all about. I uploaded the completed results to GitHub here … but again, none of that code is mine. Also, keep in mind that my repo is tied to preview/alpha builds, and I can’t guarantee I’ll keep it up to date when this stuff goes to release status (although I’m hoping Philipp will run with these changes and produce a Core-friendly NuGet package).

I didn’t want to clutter up my machine with pre-release code, so I fired up a VirtualBox VM with Win10 Pro and installed the .NET Preview SDKs and Visual Studio 2019 Preview there. The only real stumbling block I encountered relating to the SDKs was that some namespaces were missing in Preview 1, so I had to install one of the daily builds for the fix. The GitHub discussion is here, the fix will be in Preview 2 (coming soon but not yet available as I write this).

Creating the Library Project

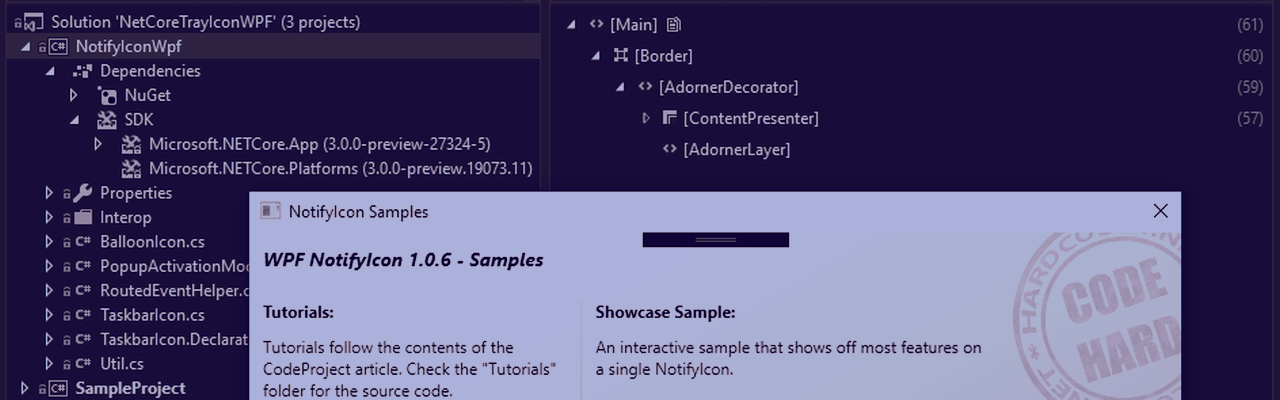

The important parts of Philipp’s code are provided by a library project, so I began by creating a new solution, and inside that I created a new .NET Core 3.0-based library project. After removing the default Class1.cs file, I simply copied the code from the old .NET Framework version to my new project’s folder, excluding the Properties folder and the AssemblyInfo.cs file it contains (more about that later).

At this point I took a look at the code and not surprisingly, there were many missing System.Windows.* references. I knew I needed to reference the new Windows Desktop SDK, but how?

Microsoft has explained that the VS 2019 preview doesn’t yet support the creation of .NET Core WPF projects. They must be created from the command-line for now. The obvious next step was to see what a .NET Core WPF project looked like inside. I knew Philipp’s sample programs would have to be created this way anyway, so I created a SampleProject folder, changed to the directory, and ran the command dotnet new wpf and after a few seconds of churning I had a new project ready to add to the solution.

At first I was a little dismayed. I opened up the new csproj and saw this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

<PropertyGroup>

<OutputType>WinExe</OutputType>

<TargetFramework>netcoreapp3.0</TargetFramework>

<UseWPF>true</UseWPF>

<RootNamespace>Samples</RootNamespace>

</PropertyGroup>

Microsoft has been doing all sorts of wonky stuff with the csproj file format lately, and unfortunately the documentation is incomplete. <UseWPF> wasn’t very helpful, so I went digging through the Solution Explorer Dependencies list where I found a reference to Microsoft.WindowsDesktop.App (3.0.0-preview-27324-5) and sure enough, after setting NuGet to show pre-release versions, I was able to find it and pull it into the other library project.

And that was literally all it took to get the library to build. I figured I was on Easy Street.

The Sample Project

Since I had already created a WPF template project in my SampleProject folder, and because the library project (which involves a lot of WPF-specific stuff) was so easy to build, I was hoping the samples would go just as smoothly. I changed the project’s default namespace to Samples to match the old project, then I deleted the default App.xaml and MainWindow.xaml and code-behind files, crossed my fingers, copied the old code, and tried to build the project.

The compiler complained about unresolved XML namespace references in about 20 XAML files. Fortunately, there were only two problems across all of those files. Many of the files have nodes which look like the following, and the x:Type argument was unresolved:

1

<ObjectDataProvider ObjectType="{x:Type sys:Enum}" ... />

This was a bit disconcerting. The x namespace has been defined by the bone-stock XAML templates for more than 10 years. Worse, the correction suggested by Intellisense looked reasonable but didn’t help at all:

1

xmlns:x1="clr-namespace:System;assembly=System.Runtime"

After a few minutes of GitHub issue-searching, I learned this was an oversight in the Preview 1 SDK’s WPF implementation (explained in the issue I linked to earlier). Installing the daily build instantly resolved that problem, and these fixes will be part of the Preview 2 SDK, due to be released soon. I wound up with the .NET Core SDK versioned as 3.0.100-preview-010184 and the Desktop SDK versioned as 3.0.0-preview-27325-3.

Unfortunately there were also a large number of unresolved project-specific references. Specifically, all references to the tb namespace, which is the home of all the TaskBar* classes defined by the library project. This namespace was defined at the top of each XAML file as follows:

1

xmlns:tb="http://www.hardcodet.net/taskbar"

This time the suggested fix from Intellisense worked:

1

xmlns:tb="clr-namespace:Hardcodet.Wpf.TaskbarNotification;assembly=NotifyIconWpf"

However, I didn’t like that such a radical change was necessary. If you’re an experienced WPF developer, the issue is probably as plain as day. I hadn’t worked with WPF in several years and had forgotten that assemblies can define custom XML namespaces. Worse, I searched the library project for that namespace string and it wasn’t anywhere to be found.

Earlier I wrote that Microsoft has been making sweeping changes to the csproj file format, and one of those changes was to move many of the attributes formerly defined in AssemblyInfo.cs (such as Company Name) to csproj XML nodes. As a result, a .NET Core project doesn’t include the venerable Properties folder or an AssemblyInfo.cs file by default, and when I had copied the old code, I ignored those as a matter of course. As any experienced WPF developer can tell you, custom XML namespaces are defined there, so that was the fix.

I created a Properties folder in the library project, added a new AssemblyInfo.cs file with the following code, and recompiled. The references in the sample project were resolved. (Technically this code doesn’t need to be stored in AssemblyInfo.cs, nor is there any requirement to store it in a folder named Properties, but I didn’t have any particular reason to break with tradition.)

1

2

3

4

using System.Windows.Markup;

[assembly: XmlnsPrefix("http://www.hardcodet.net/taskbar", "tb")]

[assembly: XmlnsDefinition("http://www.hardcodet.net/taskbar", "Hardcodet.Wpf.TaskbarNotification")]

At this point the sample project compiled and ran. Hooray!

This time, however, I did remember enough about WPF to realize the resource dictionaries also needed to be defined as assembly attributes. In the sample project folder, I again added an AssemblyInfo.cs class to a new Properties folder, this time with the default resource dictionary definition. (I also opened a GitHub issue where we’re discussing the suggestion that the default template should include these assembly attributes.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

using System.Windows;

[assembly: ThemeInfo(

ResourceDictionaryLocation.None,

ResourceDictionaryLocation.SourceAssembly

)]

Missing Resources

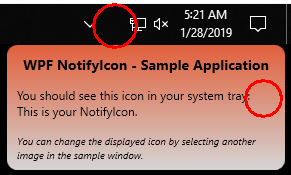

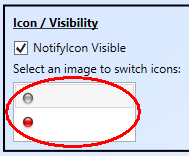

At this point the program ran, but all of the images were missing. The sample should show a gray dot icon in the System Tray area and in the balloon pop-up, but instead it was blank. The icon had been successfully created in the System Tray area since the gap was visible, but the graphics were missing. Then I noticed graphics were missing everywhere else, too.

This was annoying because I knew I’d correctly defined the resource dictionary attributes. I noticed the old project had a Resources.resx file, and it turns out .NET Core resource files are currently limited to string data only (discussion here), but that was a false lead – it didn’t have many of the images that were missing, and that file isn’t used by the project (although it’s needed for the tutorial Philipp posted to CodeProject). I could see the *.ico and *.png files that the resource dictionaries referenced.

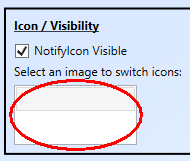

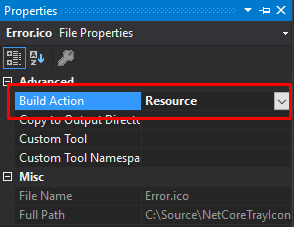

I had once again forgotten a part of WPF which older Visual Studio versions handled automatically, but was not working correctly in the VS2019 Preview release: files destined for storage in a resource dictionary must have their Build Action property set to “Resource”. There is an open issue here about this VS2019 problem.

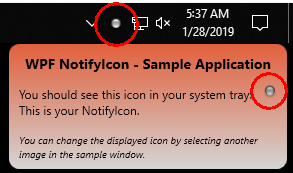

With this easy fix, the sample project was fully functional!

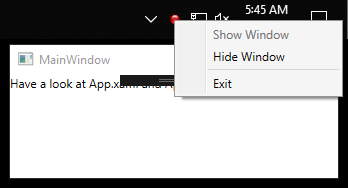

Windowless Sample

The other useful sample project is the windowless version of a System Tray icon. Right-clicking the icon displays a context menu which can open and close a separate window on demand. There isn’t a lot to say about this one, it required exactly the same steps used to get the more elaborate sample project working. The only gotcha I ran into was that I forgot to check and set the correct default namespace, which should be Windowless_Sample which caused the build of the resource dictionary to fail.

Conclusion

As the introduction suggested, I was pleasantly surprised at how complete WPF support seems to be in this early alpha release. I later copied several other WPF applications and everything I tried just worked out of the box, project configuration details notwithstanding. Despite the entire stack being in preview status, I didn’t encounter any bugs at all. I was able to debug into the projects without issues, they ran stand-alone just fine, and so on. Pretty impressive if you ask me, WPF is neither small nor simple.

Are you an enterprise web-app developer who thinks desktop apps have lost their relevance? Question your assumptions!

Whatever reasons you may have to build Windows desktop applications, I highly recommend setting up a VM and giving these preview bits a test drive.

Comments