Learning to Program Part 2, Data Types and Debugging

A beginner-level programming series.

In Part 1 of this series, I explained how variables allow programs to perform tasks on different pieces of information, such as user input. In that article, we used variables to hold numbers as well as text. In most programming languages, a variable which holds text is called a “string”. Strings are just one of many data types, a term that describes the kind of information that a variable can store. Today we’ll talk a bit more about data types, because they’re pretty important in most languages.

Programmers say a language is loosely typed or strongly typed. Most languages are strongly typed, which means a variable can only store a specific kind of information – the variable’s data type, often abbreviated to just type. The most popular loosely typed language is JavaScript, which is mostly used in web browsers. Usually even loosely typed variables are used in a strongly typed way, because it can be very difficult to deal with variables that change the kinds of information they store. I won’t be spending time on loosely typed languages in this series.

We’re also going to talk about a common programming chore called debugging, which is the process of identifying logic errors in a program. I’m trying to avoid geting into specific language details for the early parts of this series, and the details of debugging are often tightly tied to both the language itself as well as the tools used to write programs (collectively known as Integrated Development Environments, or IDEs), but even at this early stage, mistakes are easy to make. (All programmers make mistakes, and it has been suggested that all software contains undiscovered bugs.)

Bugs and Debugging

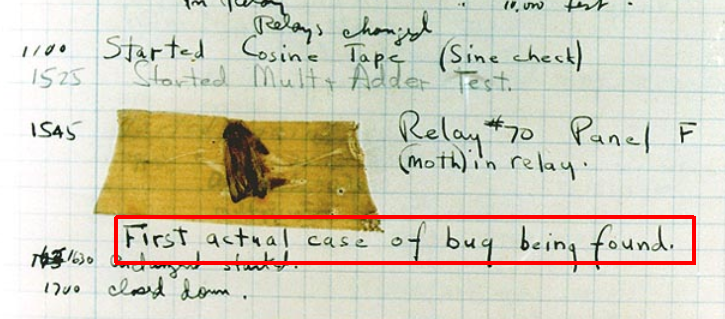

Most likely you’ve heard the computer term bug which refers to a flaw in the logic of a program. Although the term is a very old way of describing any technical design problem (Wikipedia’s History section has non-computer-related examples from the 1870s), there is an amusing story from 1947 in which an actual bug – a moth – caused a problem in Harvard’s Mark II computer. They even taped the moth to the logbook documenting the day’s work next to the note, “moth in relay”:

You’ve probably also heard the term debug which refers to the process of (hopefully) fixing a bug. Programmers spend a lot of time debugging. Modern computer languages and their IDEs are very good at catching some typos and other simple misuse of the language, but logic errors are harder to spot.

One of the short, simple programs in the first article in this series had a bug. The section titled Functions explained why functions in most programming languages follow the formatting of functions from the world of math, which is f(x). Specifically f is the name of the function, and (x) lists the variables passed into the function (called parameters or arguments). I’ve already fixed the first article (so that the mistake won’t confuse new readers), but this is the code with the bug:

1

2

3

4

5

6

print("Enter the price:")

listPrice = input()

salesTax = listPrice * 0.07

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

print("Please pay:")

print totalCost

The last line is missing a pair of parenthesis. It should read:

1

print(totalCost)

This is an example of the type of bug a modern development environment will probably catch – most likely as you’re typing the code. Generally we refer to such mistakes as syntax errors and the development environment usually won’t even let you try to run a program with a problem like this.

The kind of bugs you’re more likely to encounter after the program is written are logical errors. For example, the output of the program above would be very different if the salesTax calculation multiplied the listPrice by 0.7 instead of 0.07. You can see how such a mistake could be easy to make, yet the IDE has no way to know whether the calculation should use 70% or 7%, so it would happily run the program either way.

I won’t say too much more about bugs and debugging, but the existence of a typo in the very first installment made this a great opportunity to explain the concept.

Data Types

In the first article, we discussed two kinds of variables – numbers and text strings. These were the variables’ data types, or types. In real programming languages there are usually many numeric types, often at least two text types, and usually other specialized types for specific information like dates. There is even an object data type in most languages that can refer to almost any kind of data (which usually comes with a lot of restrictions), but we won’t worry about that one until a later article.

It’s safe to say that most languages at least have two numeric types. One can hold integer values and the other can hold decimal values. Why? Because calculations with integers are much faster. Also, programmers often use numbers as “codes” to represent other information. For example, a variable whose value is 1 may represent the color red, while the value 2 may represent white, and 3 is blue. In such cases, having the ability to represent fractional values like 1.5 isn’t useful.

Many languages have at least two ways to represent text – a character type, which can hold exactly one character, such as “A” or “@”, or the string type we talked about in the first article, which is any group of characters, such as “hello” or “who’s a good dog?”

Usually a program has to explicitly tell the computer what kind of data a variable will hold. We call this declaring the variable. Let’s go back to our made-up language from the first article. Most languages have a keyword called string which identifies a text data type, and we’ll assume our language also has a decimal keyword to identify a numeric data type that can store decimal data (many languages actually do have a decimal type).

This the sales tax example with some new lines at the beginning which declare several variables. This way the computer knows what kind of data each type of variable can store:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

decimal listPrice

decimal salesTax

decimal taxRate

decimal totalCost

string prompt

prompt = "Enter the price:"

print(prompt)

listPrice = input()

salesTax = listPrice * 0.07

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

print("Please pay:")

print(totalCost)

Data types have default values. If you check the value of listPrice immediately after declaring it as a decimal, it will be zero. In most languages, you can provide a starting value for the variable when you declare it, so we could combine the string prompt declaration with the next line that sets the value. We call this initializing the variable:

1

2

string prompt = "Enter the price:"

print(prompt)

Sometimes programmers use variables even when the value won’t change. In this simple program, we could use a taxRate variable to store the value 7%, which would reduce the chances of accidentally typing 0.7 somewhere in the program instead of 0.07. A variable that isn’t meant to change is called a constant. (We won’t spend time on it here, but many languages have special features to support constants, such as ensuring the value isn’t changed somewhere else in the program.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

decimal listPrice

decimal salesTax

decimal totalCost

decimal taxRate = 0.07

string prompt = "Enter the price:"

print(prompt)

listPrice = input()

salesTax = listPrice * taxRate

totalCost = listPrice + salesTax

print("Please pay:")

print(totalCost)

Data Types and Memory

Although I’ve used many computer languages in my life (I stopped counting at close to 50 – a long, long time ago), for most of the past 20 years, I’ve primarily used a language called C# (prounounced “C sharp”). There is a whole family of “C-like” languages based on an old (but still popular) language called simply C. I don’t want these early articles to be too language-specific, but I do want to talk about some real-world data types, and most of those I’ll describe are similar across many languages, especially C-like languages.

Data types have some rules that will seem strange to a beginning programmer. For example, most languages have an integer type but they also have something called a long integer. In the same way that an integer can’t store decimal values, an integer can only store a limited range of numbers. The long integer exists because it can store a much larger range of numbers. The ranges are language-specific, but I’ll show some examples in a moment.

You’ve probably heard the word byte, which is one of the smallest units for measuring computer memory. A byte is a way of representing a number from 0 to 255. You’ve probably also heard that computers operate on ones and zeros – these are called bits and one byte is 8 bits. A bit can have two states (one or zero), so eight raised to the power of two is 256. This is why a byte can store a number in the range of 0 to 255. Earlier I mentioned the character data type, which can hold a single character like “X” or “!”. Early computers only recognized 256 different characters, because one byte represented one character and it was stored as a number (0 to 255). Modern characters are a lot more complicated, but we won’t get into that any time soon. The important part is that the amount of memory a data type uses is closely related to the amount and range of data a variable can store.

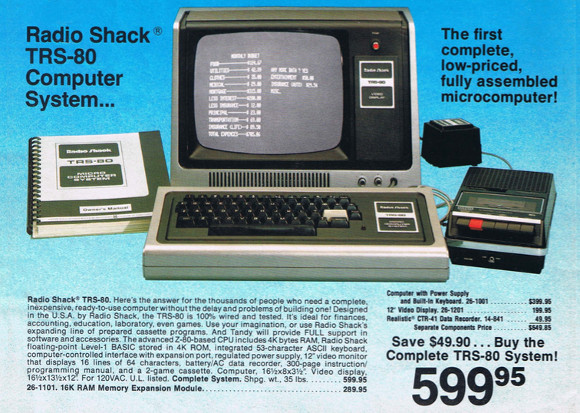

In the old days, computers didn’t have much memory. We often had to be very careful with the data our programs stored and used. Way back in 1978, my first computer, a TRS-80 Model I, had just 4K of memory – 4096 bytes. That’s not much memory – the first article I ever posted on my blog is more than 3K (not including the pictures) and it’s just four short paragraphs. (Yes, that’s a cassete-tape deck next to the keyboard, that’s how we stored programs and data.)

Examples of Data Types

Other than the types and ranges of information that can be stored by each data type, each data type uses different amounts of memory. Modern programmers mostly don’t worry about that too much, but that factor still imposes certain technical limitations on most data types, which is why an integer data type supports a smaller range of numbers than a long integer data type – the long integer is stored across more bytes of memory.

For example, in the C# language that I use most often, the integer data type, called an int (or sometimes Int32 because it is stored as a 32-bit number, which is 4 bytes), can represent the range of values from -2,147,483,648 to 2,147,483,647. If you need an integer over 2.14 billion, you need to use the long integer data type, called simply long. That’s an 8-byte (64-bit) number that can represent -9,223,372,036,854,775,808 to 9,223,372,036,854,775,808.

Most languages also have several kinds of decimal data types. Fractional numbers are harder for a computer to store and calculate with, and for highly technical reasons, they have varying levels of accuracy. For example, one kind of decimal data type is called a float because the decimal point is said to be “floating”, which has to do with the way the fractional portion is stored. Floating point math is very, very fast so it’s popular in graphics applications where speed is more important than accuracy. In fact, modern 3D graphics cards are mostly just super-fast floating point math processors. However, you’d never want to use it for financial calculations where the errors can be significant. Most languages also have single and double types, standing for single-precision and double-precision (which relates to the accuracy of the fractional portion). The double-precision data type is commonly used for financial calculations, but some languages have money or currency data types, some have a decimal data type, and specialized languages may have much more exotic numeric data types.

Many languages also have “unsigned” versions of these data types. You’ll notice the range of an int is negative two billion to positive two billion. If you don’t need to work with negative numbers at all, you can double the largest number using the same amount of memory. (The negative/positive indicator uses up one of those 32 bits used to store the int, so if you use that for data instead, the power-of-two factor means the largest value is doubled.) An unsigned integer, called a uint, has the range of 0 to 4,294,967,295. It is also a 4-byte value. You probably won’t see these used very often, however.

Specialized Data Types

Programs frequently need variables to track whether something is true or false. It may indicate the outcome of some previous operation, it could track a user’s preference, the availability of some external resource, or literally any other thing you can imagine that has a definite true-or-false state. In our little sales tax program, for example, we might use a true/false variable to indicate whether the item is tax-free. If true, we would skip the tax calculation completely.

In the old days we’d just store an integer 0-or-1. Normally 0 indicates false and 1 indicates true, but there were cases where -1 was treated as true, and less-clear cases where 0 meant an operation was successful, which you’d normally think of as true. This kind of ambiguity is a common source of bugs, but for many years we simply had no choice.

These days, many languages represent true/false with a specialized data type known as the Boolean, which is often declared as bool. This strange name was chosen in honor of George Boole, a famous mathematician from the 1800s. He invented a type of algebra that only involves the values zero and one, which is obviously a pretty important concept in the computing world. As you have probably guessed, a bool variable can only store one of two values. For convenience, most languages work with the special keywords true and false instead of the literal numeric digits “0” and “1”, which helps us avoid any ambiguity. (Some languages also have a bit data type which does use the numeric representation, but those are typically used for actual numeric Boolean operations, rather than true/false indications.)

In a later article we’ll talk about ways to conditionally run code, where you’ll see how true/false values are very important.

The point where most languages diverge completely is how they support other specialized data. For example, date-and-time in the language I use is often stored in the DateTime data type, or a newer, more accurate variation called DateTimeOffset. Many other languages have the same concept, but they generally are not standardized to the same degree. For example, another popular programming language called Java also has a DateTime data type, but the details of how you work with that data, and even basic concepts like the supported range of dates are almost completely different.

Conclusion

In this installment we took a brief look at programming mistakes, called bugs, and the process of fixing them, called debugging. We also reviewed how variables in a program are declared as different data types, which controls the type of information they hold. We then reviewed of some real data types and how they differ. All of these concepts are a basic part of every programmer’s day to day work.

So far, we’ve worked with a made-up language and a very short, simple program: it only does one thing, and it only runs once then stops. In the next installment, we’ll start looking at ways to control the flow of a program using other foundational concepts that programmers use all the time.

Comments