Event Sourcing with Orleans Journaled Grains

Event sourcing with logging and snapshots for Microsoft Orleans

Earlier this summer I began playing around with Microsoft Orleans, a “virtual actor model” framework for building and running microservices with features like automatic cluster load-balancing. One-off services, called “grains”, are very easy to create. I recently wrote a couple of articles (Sept-18 and Nov-04) about this.

There are a few architectural concepts that are commonly employed as part of a business-oriented microservices-based platform. These are domain-driven design (DDD), event sourcing (ES), and command-query responsibility separation (CQRS). Event sourcing itself adds two more concepts, event stream logging, and snapshots. Orleans offers something called a “journaled grain” which is supposed to provide event sourcing support.

This article is an exploration of how to get a realistic implementation of that working. The Orleans documentation is badly out of date, many of the code samples are incomplete or unclear, and the only event sourcing sample code is many years out of date. Additionally, it’s difficult to understand how the sample code relates to real-world usage. I hope to correct all of that with this article.

The repository for this article can be found on Github at OrleansEventStreamLog. It is based upon .NET Core 3.0 and Orleans 3.0.

Architecture Buzzwords

Although many of these concepts can be applied to things like games or spreadsheet applications, I’ll work from the assumption that we’re interested in enterprise-style in-house line-of-business software. You could spend weeks reading definitions, discussions, and arguments about what all of these things mean, and advice about what to do, or not do. I’m going to do a 50,000 foot view, not because I want to throw my hat into that arena, but because I want to talk about how they’re related.

You can think of domain-driven design as the combination of a business-oriented data model (the “domain model”) and capturing how the business manipulates the data stored in that model. I’ve been working on a large, complex domain model recently, and one useful rule of thumb we apply is to ask whether a non-technical business person would understand each object or data element and the relationships to other parts of the model. If not, it’s probably a technology concern and doesn’t belong in the model. There are a lot of other concepts that go along with DDD with complicated-sounding names like “ubiquitous language” and “bounded contexts” (and they’re important concepts), but “pure-business data model” is a good quick-and-dirty explanation of the primary goal of DDD.

Command-query responsibility separation, or CQRS, is rooted in the concept that many data storage systems can be optimized for reads or writes, but exhibit less-optimal performance when reading and writing is mixed. The high-level idea is that you separate your APIs and the underlying data according to write-focused activity (commands) and read-focused activity (queries). This ends up being a good match for the business operations captured by domain-driven design. You can think of CQRS-style services as the API for working with the domain model. (In more complex, real-world systems, it’s more common to have another layer sometimes called the API Gateway or Aggregation layer, which then talks to individual CQRS services, but that’s an implementation detail not relevant to this article.)

Event sourcing is a natural extension of DDD and CQRS. The basic concept is that a series of events are used to describe the evolving state of the domain model. As commands (reflecting business operations) are issued to the CQRS service layer, the service emits events (“domain events”) which represent how those commands changed the model. Thus, events are always described using past-tense names, and they are persisted to some storage medium. In other words, events are logged. In ES terms, the log becomes the domain model’s “source of truth” – if it isn’t in the log, it never happened, and logged events are never changed, the log is append-only.

The term “event stream” is often used to refer to the series of logged domain events applied to a given domain model. Theoretically, a pure event sourcing system will “replay” the full event stream to determine the current state of the domain model. In practice this is usually impractical, so ES introduces the concept of snapshots – a point-in-time dump of the domain model, which can be used in place of replaying the logged events leading up to the snapshot.

It’s important to understand that these concepts should not be applied to the system as a whole. In particular, it took me a long time to warm up to the idea of event sourcing. However, each time I employed DDD and CQRS, I found myself also building what amounted to ES. In my case, the problem I had with ES is that the examples I had seen were so over-simplified that it was difficult to understand why anyone would bother. For example, everyone seems to love the stereotypical online shopping-cart example, and trivial features like logging an event to change the quantity of an item in the cart. And in fact, many teams struggle with the granularity of their events. ES began to make sense to me when it arose naturally from truly business-oriented DDD and CQRS implementations. No business user would describe changing a shopping cart quantity as a discrete business operation, but changing the shipping address might be. Once you get the granularity right, the concepts start to click together cleanly and the value becomes obvious.

Although the primary focus of the article is how to implement event sourcing using an Orleans JournaledGrain, this article is also an attempt to provide a realistic, yet easy-to-grasp example of these architectural concepts.

Domain Model

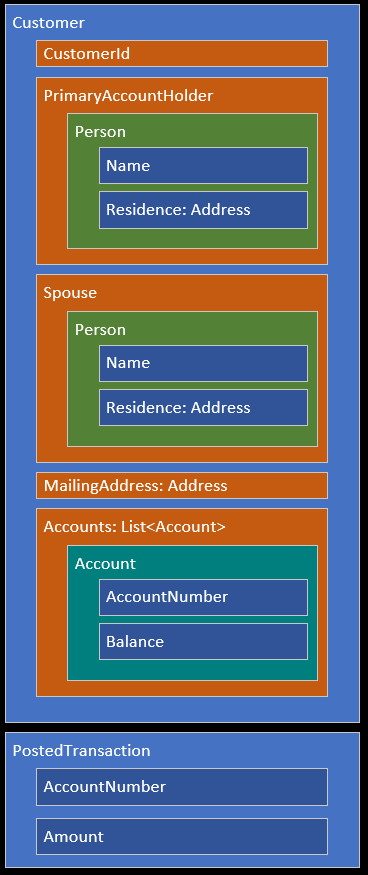

I work in the financial sector, so I decided to model a simple banking customer’s data. These are POCO (Plain Old C# Object) classes – just easily serializable fields, no methods or other code at all (not even property accessors, although they’re usually a good idea for a real-world implementation). The solution has these in a library project called DomainModel. There are just five classes, although some are reused in interesting ways.

The root element is the Customer class, which has a CustomerId string field, two instances of the Person class, which are the PrimaryAccountHolder and Spouse fields, an Address field called MailingAddress, and a generic list of Account objects. Additionally, each Person class has its own Address field named Residence, plus the usual information like name and tax ID. The Account class has fields like AccountNumber and Balance. Finally, there is one more class not directly referenced by the others called PostedTransaction, which stores an AccountNumber, an Amount, and other relevant information such as a timestamp. We’ll see how PostedTransaction relates to the model towards the end of the article.

Domain Events

As explained earlier, domain events describe (in past-tense language) changes that were made to the domain model data. A well-designed domain model tends to naturally reflect how it interacts with the necessary business operations, and as a result, the domain events often flow naturally from this relationship.

Looking at our model above, we can imagine events such as updating addresses or adding new accounts. I settled on the following domain events for this model. The last one is a special case that I will discuss later. Domain events are represented as classes which are also part of the DomainModel library.

CustomerCreatedAccountAddedAccountRemovedMailingAddressChangedResidencePrimaryChangedResidenceSpouseChangedSpouseChangedSpouseRemovedTransactionPostedInitialized

Clearly a real banking system would have many more associated operations and events, but this is a pretty robust list for example purposes, and some have interesting characteristics.

Commands and Queries

Because this domain model is so simple, the CQRS commands are just a one-to-one mapping for each event. However, in a real system, a given command could trigger none, one, or many events depending on the data, inputs, and applicable business rules. Our command list looks like this:

NewCustomerAddAccountRemoveAccountUpdateMailingAddressUpdatePrimaryResidenceUpdateSpouseResidenceChangeSpouseRemoveSpousePostAccountTransaction

You can see how commands are action-oriented business operations, whereas the corresponding domain events are past-tense descriptions of what changed.

Our system has a relatively simple set of CQRS queries:

FindCustomerFindAllCustomerIdsCustomerExists

The commands and queries are handled by Orleans StatelessGrain classes called CustomerCommands and CustomerQueries, respectively. The solution has these in the ServicesCustomerAPI library project. The StatelessGrain feature allows one or more copies of the grain to run locally on each Orleans silo server, which significantly improves response time. The classes are also marked as Reentrant which means it’s safe to interleave the calls, further improving overall throughput.

Event Payloads

Earlier we said that the logged events describe changes to the domain model. We call this “mutating state.” There are other theories about how to implement event sourcing, but the approach we’ll take is often referred to as logging “deltas”. Only changes are logged. This implies that the logged event must contain the details of what changed. Each of the domain events listed has different fields that specifically describe the change.

For example, the AccountAdded event contains an instance of the Account class from our domain model. Similarly, the AccountRemoved event contains an AccountNumber field. Events are cumulative, moving forward in time, so you wouldn’t store the entire Account object for the AccountRemoved event – it’s already in the aggregate domain model from some earlier AccountAdded event logged in the event stream. One interesting event is SpouseRemoved which has no additional fields. When that event is triggered, the Customer.Spouse field is set to null and no further information is required other than the event itself.

How are these events sequenced? A simple integer does the job. Each domain event class inherits from a base class called DomainEventBase. The base class adds two fields – a Timestamp and something called ETag which is the integer sequence value. The term “ETag” stands for entity tag and was originally used in HTTP synchronization, but has become popular in other areas such as database operations. Many event sourcing systems call this a version instead of ETag. Orleans mostly refers to versions as well, but the concept is identical for our purposes, and I prefer ETag because “version” is often a reserved keyword in many languages, including TSQL.

Database Support

The project assumes you’re using SQL Server. There is a connection string hard-coded into the CQRS CustomerCommands and CustomerQueries classes, and in the grain CustomerManager class, and those classes also have hard-coded SQL statements. It assumes the use of a database named OrleansESL in the SQL Server local-instance installed with Visual Studio.

This project needs two database tables – one to store the sequence of events, and another to store periodic snapshots of the entire domain model. The table definitions are shown below. The script in the repository has some additional comments and some index definitions, but there’s nothing terribly interesting or surprising about this part of the system.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[CustomerEventStream] (

[CustomerId] VARCHAR (20) NOT NULL,

[ETag] INT NOT NULL,

[Timestamp] CHAR (33) NOT NULL,

[EventType] VARCHAR (MAX) NOT NULL,

[Payload] VARCHAR (MAX) NOT NULL

);

CREATE TABLE [dbo].[CustomerSnapshot] (

[CustomerId] VARCHAR (20) NOT NULL,

[ETag] INT NOT NULL,

[Snapshot] VARCHAR (MAX) NOT NULL

);

Log Consistency Providers

Orleans JournaledGrain classes need something called a “log consistency provider.” You can think of this as a kind of manager which orchestrates the logging of domain events and the evolution of the associated domain model state.

Orleans provides three log consistency providers, but surprisingly, none of them are considered ready for production usage out-of-the-box. The StateStorage provider doesn’t actually log events at all, it only logs the final result of applying those events. It is a snapshot-only implementation. The LogStorage provider is the exact opposite, only storing events and never snapshots, and always replaying events when the grain is activated. It is a pure event streaming implementation.

We’re interested in the third log consistency provider, called CustomStorage. At first glance, implementation doesn’t seem too complicated. The interface requires you to implement two methods, ReadStateFromStorage and ApplyUpdatesToStorage. As you’ve probably guessed, the devil is in the details.

For the rest of the article, we’ll assume we’re implementing the CustomStorage approach. Some of my statements wouldn’t apply to other approaches, but again, the Orleans team themselves don’t recommend using the other providers except experimentally.

Journaled Grains

The classes and interfaces in this section can be found in the ServicesCustomerManager library project.

An Orleans JournaledGrain has several important duties to perform. It must manage the domain model state, which includes reading from storage as well as applying new events, and it must manage the persistence of new events to storage. I named this class CustomerManager for reasons I’ll explain later.

Defining a JournaledGrain requires identifying the class which represents the domain model state, and the base class for domain events. We discussed DomainEventBase earlier, but the class representing the domain model state must provide more functionality than is appropriate for our POCO domain model. Namely, it is expected to mutate state by applying the domain events. (You can omit the event base class, in which case Orleans will just use object, but we must declare it because our base class has additional fields that apply to all events – which is likely to be the case for any real system.)

The documentation shows two approaches for managing domain model state changes. Either the state class itself can expose many Apply overloads with a arguments matching each of the domain events, or the grain class can override one big TransitionState method which presumably uses something like a switch statement to process each domain event. There are pros and cons to each approach. The one-big-method option seemed rather clumsy, although it would encapsulate all event sourcing behaviors within the CustomerManager grain. However, the Apply-overloads approach results in code that I found easier to read, so I created a new class, CustomerState, which inherits from our Customer domain model. This subclass is where you’ll find the various Apply overloads.

Earlier we mentioned that the domain events have payloads relevant to the event. This is what the method looks like for applying the MailingAddressChanged event. It simply reassigns the MailingAddress field (inherited from the Customer domain model base class) to the Address object attached to the domain event.

1

2

3

4

public void Apply(MailingAddressChanged e)

{

MailingAddress = e.Address;

}

Remember that business logic is in the API Gateway and/or CQRS layers (and ideally, further separated into a business rules library, for a real application). At this level the decision has already been made to change the data, we’re simply making that change happen.

Orleans makes heavy use of interfaces. The grain interface initially looked like this, although later we’ll change this to require one more interface:

1

2

3

4

public interface ICustomerManager

: IGrainWithStringKey,

ICustomStorageInterface<CustomerState, DomainEventBase>

{ }

Like any normal grain, it declares the data type of the primary key (the grain’s unique identifier), which in our domain model will match the CustomerId string field. It also requires implementing the ICustomStorageInterface which also declares the domain model state class and the domain event base class described above. The grain base class itself also declares the state and event classes, and this also shows the default implementations for ICustomStorageInterface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

public class CustomerManager

: JournaledGrain<CustomerState, DomainEventBase>,

ICustomerManager

{

public async Task<KeyValuePair<int, CustomerState>> ReadStateFromStorage()

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

public async Task<bool> ApplyUpdatesToStorage(IReadOnlyList<DomainEventBase> updates, int expectedversion)

{

throw new NotImplementedException();

}

}

Figuring out how to implement those two methods is where the “fun” begins.

ReadStateFromStorage

The Orleans documentation provides this guidance, which is simple enough:

ReadStateFromStorage is expected to return both the version and the state read. If there is nothing stored yet, it should return zero for the version and a state that matches corresponds to the default constructor for StateType.

Considering that we’re storing both the event stream and snapshots, this means the method must perform the following steps:

- Create the state object (this corresponds to ETag, or version, zero).

- Read the latest snapshot, if any, and update the ETag to match.

- Apply any newer events that were logged after the snapshot (by ETag).

- Return the ETag and the final state.

And that’s exactly what it does. (The single-line non-block-scoped version of the using statement is new in C# 8.0, which required changing all of the solution’s library projects to target netstandard2.1 instead of the default 2.0 target.)

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public async Task<KeyValuePair<int, CustomerState>> ReadStateFromStorage()

{

using var connection = new SqlConnection(ConnectionString);

await connection.OpenAsync();

var (etag, state) = await ReadSnapshot(connection);

var newETag = await ApplyNewerEvents(connection, etag, state);

if (newETag != etag) await WriteNewSnapshot(connection, newETag, state);

etag = newETag;

await connection.CloseAsync();

return new KeyValuePair<int, CustomerState>(etag, state);

}

The method returns a KeyValuePair as a sort of poor-man’s tuple since Orleans event-sourcing support dates back to the C# 5.0 days. Since C# has real tuple types now, our custom private ReadSnapshot method returns one of those instead. If there is no snapshot in the database, etag is zero and state is a new CustomerState object with only the CustomerId field initialized (matching the primary key used to create the JournaledGrain instance).

Now that we have some type of state available, we call the private ApplyNewerEvents method, passing along the etag we got from the snapshot call. Any logged events with a higher etag will be “replayed” by calling each event’s Apply method on the domain model state object. The state argument is modified directly, and the method returns the new etag.

One quirk of JournaledGrain is that it doesn’t provide any convenient places to periodically write updated snapshots. Later I’m going to look at options like pub/sub, as it’s commonplace to handle snapshots out-of-band (in ES terminology this is often called a “projection”), but this project simply updates the snapshot after newer events have been replayed. We compare the final replay etag to the snapshot etag, and if the new one is different, we call our private WriteNewSnapshot method. Snapshots are serialized with JSON.Net.

Finally, we return the etag and state class in a KeyValuePair.

Applying Logged Events

There isn’t much to say about the private methods used by ReadStateFromStorage, with one exception. In the middle of the SqlDataReader loop in the ApplyNewerEvents method, the logged events are deserialized as the DomainEventBase class:

1

2

3

4

5

var eventbase =

JsonConvert.DeserializeObject(payload, JsonSettings)

as DomainEventBase;

state.Apply(eventbase);

JSON.Net is able to deserialize the real event class type (thanks to the TypeNameHandling setting), but because .NET is statically-typed, our code has to reference the base class. Originally I used a giant switch statement to map the base class to the correct derived class, similar to this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public void Apply(DomainEventBase eb)

{

switch (eb)

{

case AccountAdded e:

Apply(e);

break;

case AccountRemoved e:

Apply(e);

break;

case CustomerCreated e:

Apply(e);

break;

// etc.

}

}

It was ugly, but I liked it better than the use of dynamic in the Orleans default implementation of TransitionState (which you can see in the source here). However, with just two lines of reflection code in the ApplyNewerEvents method, that last line (state.Apply(eventbase)) goes away, becoming:

1

2

3

4

5

MethodInfo apply =

typeof(CustomerState)

.GetMethod("Apply", new Type[] { eventbase.GetType() });

apply.Invoke(state, new object[] { eventbase });

Given the overhead of the Dynamic Language Runtime, I’m not sure why Orleans doesn’t do it this way.

Grain Primary Key

Another minor item that bears mentioning is accessing the grain’s primary key.

Our JournaledGrain was declared with a string-based primary key, and we’ve mentioned that it corresponds to the CustomerId value in our domain model (a field in the Customer class). For most grains, you can reference this any time by calling GetPrimaryKeyString. However, this wasn’t available for a JournaledGrain, which was annoying since I wanted this to initialize a new CustomerState instance. It turns out that it’s accessible by casting the JournaledGrain object to Grain, which led to this property getter:

1

2

3

4

private string GrainPrimaryKey

{

get => ((Grain)this).GetPrimaryKeyString();

}

ApplyUpdatesToStorage

Long before I wrote any code, I suspected the ApplyUpdatesToStorage method was going to be trouble, and I was right. The arguments are a list of new events to store, and an etag number called expectedversion. Of this last argument, the documentation says:

[the method] must return false if the expected version does not match the actual version.

This left me scratching my head. The actual version before or after I write the events to storage? I decided to check the source code. The abstract version has a summary tag which says:

Applies the given array of deltas to storage, and returns true, if the version in storage matches the expected version. Otherwise, does nothing and returns false. If successful, the version of storage must be increased by the number of deltas.

To me, this sounds like expectedversion is supposed to match the version after the events are persisted to storage, but in fact, the opposite is true. The expectedversion argument represents the newest event already in storage that the log consistency provider is aware of. This makes sense in hindsight: Orleans does this in case some other silo in the cluster running the same JournaledGrain (with the same primary key) has written new events to the stream that this silo is unaware of, but it took a great deal of trial and error to figure that out.

At first glance, the method must perform the following steps:

- Get the etag of the newest event already in storage.

- If the etag doesn’t match

expectedversion, exit withreturn false. - For each event in

updates, increment the etag and write to storage. - Exit with

return true.

This immediately causes a problem. The default state is treated as etag #0, as required by the ReadStateFromStorage method. However, the default constructor state doesn’t actually correspond to a logged domain event. It’s a side-effect of some other domain event – in our system, calling the NewCustomer command issues a CustomerCreated event. That would be passed to ApplyUpdatesToStorage in the updates argument. However, the flow above would persist that as etag #1 – the event stream would never contain etag #0.

This required adding a special-case domain event I called Initialized. When there are no events in storage yet, Initialized is written with etag #0. I also used that special-case to write a snapshot, because SQL requires you to choose between an INSERT or UPDATE statement. We can be sure the special-case of etag #0 will always need INSERT and once we know a record exists, everything else will always need UPDATE.

Now the correct steps are:

- Get the etag of the newest event already in storage.

- If the etag doesn’t match

expectedversion, exit withreturn false. - If the etag is #0:

- Write the

Initializedevent. - Write the first snapshot.

- Write the

- For each event in

updates, increment the etag and write to storage. - Exit with

return true.

Like state snapshots, domain events are serialized using JSON.Net.

Apply Comes Last

The other thing which wasn’t clear to me from the documentation is when the changes are actually applied to the domain model state.

It turns out this doesn’t happen until after ApplyUpdatesToStorage succeeds. You can see all of the logic in the WriteAsync method of the CustomStorage provider’s LogViewAdaptor class starting here. Line 182 calls ApplyUpdatesToStorage and line 206 calls UpdateView which loops over the events calling Apply via the dynamic code linked to earlier.

This actually makes sense: the logged events are the “source of truth”, so if they aren’t logged yet, the changes shouldn’t be reflected by the model.

Actor Encapsulation

Orleans is based upon the actor model, and that model assumes the data and code are fully self-contained units. This is encapsulation taken to extremes. If we were to embrace this completely, the grain itself would be called Customer because it actually is the customer, including all the operations that can be performed on any data associated with the customer. There are pros and cons to the actor model, and this mentality is one of the cons, in my opinion.

The fact that our customer-handling system violates that assumption is why the grain is called CustomerManager instead of Customer – I wanted to clearly establish that the grain is not the model, nor does it host the business operations which can be performed against the model.

Orleans’ implementation of JournaledGrain reflects the “purist” actor-model mentality, which makes it a little more difficult to implement the separation inherent in a DDD + CQRS + ES architecture. There are two specific problems to solve. The domain model state managed by the grain is not exposed to the outside world, nor is the RaiseEvent method (and several related methods). In the world of actors, it’s assumed that those are internal to the grain’s functioning.

The grain interface we showed earlier was expanded to add an additional interface I call IEventSourcedGrain, which identifies the domain model class (not the domain model state class) and the domain event base class:

1

2

3

4

5

public interface ICustomerManager

: IGrainWithStringKey,

IEventSourcedGrain<Customer, DomainEventBase>,

ICustomStorageInterface<CustomerState, DomainEventBase>

{ }

With one exception, that new interface is simply a list of pass-through calls to the protected JournaledGrain event-signalling methods. Since Orleans is a distributed system, clients use grains through an asynchronous proxy object, so all publicly-exposed calls must be Task-wrapped.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public interface IEventSourcedGrain<TDomainModel, TEventBase>

where TDomainModel : class

where TEventBase : class

{

Task<TDomainModel> GetManagedState();

Task RaiseEvent<TEvent>(TEvent @event) where TEvent : TEventBase;

Task RaiseEvents<TEvent>(IEnumerable<TEvent> events) where TEvent : TEventBase;

Task<bool> RaiseConditionalEvent<TEvent>(TEvent @event) where TEvent : TEventBase;

Task<bool> RaiseConditionalEvents<TEvent>(IEnumerable<TEvent> events) where TEvent : TEventBase;

Task ConfirmEvents();

}

Instead of implementing that interface on the grain class, I created another class called EventSourcedGrain which inherits from JournaledGrain and provides implementations for the methods listed in the IEventSourcedGrain interface:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public class EventSourcedGrain<TDomainModel, TDomainState, TEventBase>

: JournaledGrain<TDomainState, TEventBase>,

IEventSourcedGrain<TDomainModel, TEventBase>

where TDomainModel : class

where TDomainState : class, new()

where TEventBase : class

{

// omitted: implementations of IEventSourcedGrain methods

}

The various RaiseEvent methods allow the CQRS service to raise events. Refer to the source if you’re interested in the implementations, they’re just pass-throughs to the base class.

Exposing the state is easy. I wanted to emphasize to the caller that they’re retrieving a copy of managed data, so I called the method GetManagedState. I say it’s a copy because in ES terms, the real data is the logged event stream, which only the grain is allowed to manipulate. If some external code modifies the “copy” of the domain model data, that change won’t be reflected by any logged event and that change will eventually be lost. (This also implies that the application should constantly retrieve new “copies” of the domain model data, rather than storing it or passing it around to other methods, since the copy should be considered stale as soon as it is obtained.)

The grain CustomerState data is derived from our Customer domain-model POCO, so we return that, effectivelly stripping off the Apply functionality required by the JournaledGrain system. The resulting implementation is:

1

2

public Task<TDomainModel> GetManagedState()

=> Task.FromResult(State as TDomainModel);

Finally, we have to change the CustomerManager class to derive from this new class instead of JournaledGrain:

1

2

3

4

5

6

public class CustomerManager

: EventSourcedGrain<Customer, CustomerState, DomainEventBase>,

ICustomerManager

{

// code omitted

}

Events from Commands

Now that we can access RaiseEvent from outside the grain, it’s time to implement our CQRS commands and queries. Let’s look at a simple one, the UpdateMailingAddress command:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

public async Task<APIResult<Customer>> UpdateMailingAddress(string customerId, Address address)

{

try

{

var mgr = OrleansClient.GetGrain<ICustomerManager>(customerId);

await mgr.RaiseEvent(new MailingAddressChanged {

Address = address

});

await mgr.ConfirmEvents();

return new APIResult<Customer>(await mgr.GetManagedState());

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

return new APIResult<Customer>(ex);

}

}

The Orleans IClusterClient instance was injected via the CustomerCommand constructor. It uses the normal GetGrain<T> method to obtain a proxy for the CustomerManager with the given customer ID. Next, we simply call RaiseEvent on the grain, then ConfirmEvents. This last step is important – if you don’t wait for the events to be written, the data model will not be updated and a subsequent call to GetManagedState could return a view of the domain model before the events had been applied to it.

Most of the commands are one-to-one mappings for the events they produce, but earlier we mentioned commands can result in no events, or any number of events. Earlier we also mentioned that this layer is where business logic can be implemented. Let’s look at the more complex PostAccountTransaction command:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

public async Task<APIResult<Customer>> PostAccountTransaction

(string customerId, string accountNumber, decimal amount)

{

try

{

var mgr = OrleansClient.GetGrain<ICustomerManager>(customerId);

var acct = (await mgr.GetManagedState()).Accounts.Find(a => a.AccountNumber.Equals(accountNumber));

if (acct == null) return new APIResult<Customer>("Account not found");

var oldBalance = acct.Balance;

var newBalance = oldBalance + amount;

if (oldBalance >= 0 && newBalance < 0) return new APIResult<Customer>("Insufficient funds");

await mgr.RaiseEvent(new TransactionPosted

{

AccountNumber = accountNumber,

Amount = amount,

OldBalance = oldBalance,

NewBalance = newBalance

});

await mgr.ConfirmEvents();

return new APIResult<Customer>(await mgr.GetManagedState());

}

catch (Exception ex)

{

return new APIResult<Customer>(ex);

}

}

Once again we begin by retrieving a reference to the CustomerManager grain. Next, we verify the requested AccountNumber is valid. If it isn’t, the response is a failure message and no event is logged. Otherwise we proceed to modify the account balance. If the transaction would create an overdraft, another failure message is returned and no event is logged. Finally, we set up the TransactionPosted payload and pass the event to the grain for storage and processing.

Demo Projects

The solution also contains two console programs named DemoHost and DemoClient. The host program uses the newer .NET Core Generic Host approach, which requires a little more code but is much more capable. There isn’t much to say about the host except that you should run it first, and press CTRL+C to terminate it. The logging configuration suppresses most of the log-noise generated by Orleans, leaving only Warning-level and more critical messages. (If you run the host in debug under Visual Studio, all log output will be shown in the Debug window.)

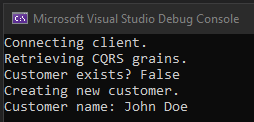

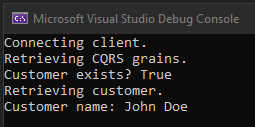

The client program is intended to demonstrate two things. At startup, it issues a query to determine whether customer ID 12345678 already exists. If it does not exist, a NewCustomer command is issued to create the customer data. It then dumps the customer name to the console to demonstrate that the domain model was updated accordingly. If the customer ID does already exist, it retrieves the domain model and again dumps the customer name to the console.

Let’s take a look at the data after these operations. On the first run, this is the client console output:

This is the host debug log output (modified to eliminate some of the ‘info’ line noise):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

CustomerCommands

NewCustomer: start

NewCustomer: get manager

NewCustomer: manager is null? False

NewCustomer: raising CustomerCreated event

CustomerManager

ReadStateFromStorage: start

ReadSnapshot: start

ReadSnapshot: exit returning etag 0

ReadStateFromStorage: ReadSnapshot loaded etag 0

ApplyNewerEvents: start for etags newer than 0

ApplyNewerEvents: exit returning etag 0

ReadStateFromStorage: returning etag 0

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: start, expected etag 0, update count 1

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: checking persisted stream version

CustomerCommands

NewCustomer: confirming events

CustomerManager

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: persisted version 0 is expected? True

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: etag 0 special-case write Initialized event

WriteEvent: start for Initialized

WriteEvent: exit

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: etag 0 special-case write snapshot

WriteNewSnapshot: start write for etag 0

WriteNewSnapshot: exit

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: update ver 1 event CustomerCreated has etag -1

WriteEvent: start for CustomerCreated

WriteEvent: exit

ApplyUpdatesToStorage: exit

CustomerCommands

NewCustomer: returning GetManagedState

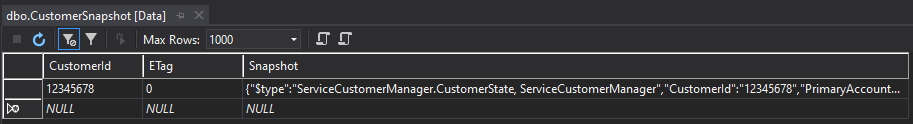

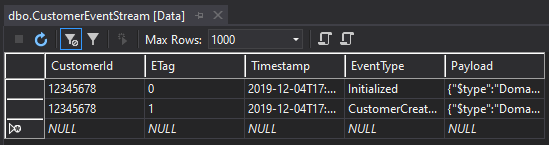

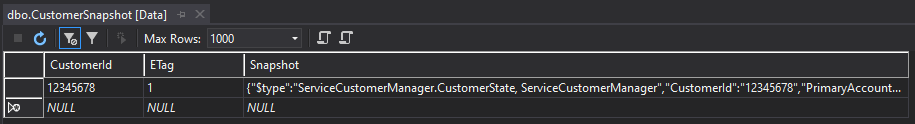

The CustomerSnapshot table only contains the etag #0 version of our domain model, which corresponds to the special-case Initialized domain event:

However, the CustomerEventStream table contains both the Initialized event and the CustomerCreated event:

On the second run, the client console output is slightly different, since the customer ID was found:

The host debug log output reflects the new processing flow (the CQRS queries were not instrumented on this run):

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

CustomerManager

ReadStateFromStorage: start

ReadSnapshot: start

ReadSnapshot: found snapshot to load

ReadSnapshot: exit returning etag 0

ReadStateFromStorage: ReadSnapshot loaded etag 0

ApplyNewerEvents: start for etags newer than 0

ApplyNewerEvents: applying event for etag 1

ApplyNewerEvents: exit returning etag 1

WriteNewSnapshot: start write for etag 1

WriteNewSnapshot: exit

ReadStateFromStorage: returning etag 1

Now the CustomerSnapshot table has been updated to a view of the domain model which includes the CustomerCreated event (notice the ETag column shows 1). Recall that updating a snapshot to match the newest event is a side-effect of the log consistency provider’s initial call to ReadStateFromStorage. Since no new events were triggered on this run, the CustomerEventStream table is unchanged.

Conclusion

This was an especially long article that covered a lot of ground. Even so, I skipped over a few points, such as the risk that ApplyUpdatesToStorage can loop endlessly if a serious problem occurs. I will be considering that problem further, and there’s a good chance it will lead to another article.

While the Orleans JournaledGrain provides a lot of functionality, I’m not yet convinced it’s the best route to Orleans-based event sourcing. However, it was necessary to fully understand how it works before drawing conclusions.

If you have use for this type of feature, or if you have experience with Orleans and/or the JournaledGrain class, I’d love to hear from you in the comments.

Comments