Blazor Login Expiration with OpenID Connect

Correctly expiring OIDC login tokens for Blazor server-side apps

In my earlier article, Blazor Authentication with OpenID Connect, we wired up a Blazor server-side application to the IdentityServer4 public demo site for user login and logout, and also demonstrated support for anonymous access to content. However, logins normally have associated expiration behaviors, and because OIDC is inherently cookie-based, which is an HTTP concept, Blazor server-side apps do not currently have a mechanism to honor the expiration since Blazor is SignalR-based, which doesn’t use cookies (or HTTP).

This article demonstrates how to solve that problem. Like the earlier article, it is based on ASP.NET Core 3.1, and I have updated the same repository, MV10/BlazorOIDC.

Expiration Options

The OIDC protocols are a bit difficult to understand. It turns out there are four ways a login can expire. Three of them are cookie-based, which is how non-Blazor ASP.NET applications ultimately manage login expiration (usually). In no particular order:

One is a simple expiration timestamp. If your login token is still valid (it hasn’t expired), but your cookie has expired, you’ll be logged out of the client. On your next trip to IdentityServer (and probably other OIDC authorities), the cookie for that domain may still be valid, in which case you’ll be automatically logged back in with no login UI presented. (This is the problem I addressed in January of 2018 in SignOutAsync and IdentityServer Cookies).

Another way is browser-session-based. The browser destroys the cookie when the user exits the browser. Setting the cookie to be persistent disables this behavior. (I addressed this scenario last year, too.)

Probably the most common approach is a “sliding expiration”. The cookie expires after a certain period of inactivity. If the user performs some server-based activity in the app (navigating to a new page, downloading content, etc.) before that timespan expires, halfway through the expiration period the server will issue a new cookie, resetting the clock on the expiration.

Finally, there is a way which isn’t directly cookie-driven: a specific point in time after which the login token is considered invalid, and the user must authenticate again from scratch. There are still cookies involved but they do not control login expiration (as long as the cookie expiration exceeds the login expiration, which is normally the case).

It’s important to note that OIDC does not provide a mechanism to renew a login short of a full new logout / login cycle. (OIDC refresh tokens only work for API-scoped access tokens. You don’t even get a refresh token back in response to a login-only auth request.)

Applying Login Expiration

The code for the earlier article just accepted whatever login expiration the IdentityServer demo happened to use by default, which is 14 days. We’ll modify the login and logout handlers in _HostAuthModel so that they each create their own AuthenticationProperties object. The login process is where we specify the desired expiration date, and we ensure the cookie is persistent to prevent cookie deletion at the end of the browser session.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public IActionResult OnGetLogin()

{

var authProps = new AuthenticationProperties

{

IsPersistent = true,

ExpiresUtc = DateTimeOffset.UtcNow.AddHours(15),

RedirectUri = Url.Content("~/")

};

return Challenge(authProps, "oidc");

}

public async Task OnGetLogout()

{

var authProps = new AuthenticationProperties

{

RedirectUri = Url.Content("~/")

};

await HttpContext.SignOutAsync("Cookies");

await HttpContext.SignOutAsync("oidc", authProps);

}

Later I’ll show some debug logging that better explains the effect of setting the ExpiresUtc property and how we’ll use it.

DIY Token Monitoring

I find it puzzling that Microsoft doesn’t appear to be too concerned that their fancy new flagship UI solution has such terrible support for authentication. You can either use their Entity-Framework-based Identity template (and all the baggage that comes with EF, not to mention reinventing the wheel for every app), or they provide integration with Azure Active Directory, and that’s it. Perhaps worse, the Azure option claims to support other models, but it does not. Worst of all, if you track down GitHub issues where people are asking for guidance about this, the answers range from “we’ll probably support that eventually” to “just go do it yourself.”

So… DIY. In the earlier article, the Index.razor page injected something called the AuthenticationStateProvider which gave us access to the authenticated identity, from which we could grab claims like the user’s name and assigned subject ID. One of the behind-the-scenes jobs of this class is to ensure the login token is still valid. In one of those passing “do it yourself” comments, someone from Microsoft posted an obsolete link that apparently demonstrated how ASP.NET Core’s Identity system does that validation. Although the link is no good, it referred to something called RevalidatingServerAuthenticationStateProvider which was the key to unlocking all of this.

The Revalidating... class is an abstract subclass of AuthenticationStateProvider which requires us to implement a RevalidationInterval property and a method called ValidateAuthenticationStateAsync. The method passes in an AuthenticationState object and a cancellation token. From there, you’re on your own, although fortunately ASP.NET Core does handle periodically calling the implementation at the defined interval. The class is completely undocumented (another ongoing gripe I have about Microsoft of late), and while it isn’t hard to understand what it should do, it wasn’t easy figuring out how to do it. But that’s why you’re here, right?

No HttpContext

There is a lot of bad advice out there about how to set up Blazor auth, which is also why I’m so annoyed that Microsoft isn’t giving the subject adequate attention or support. Since Blazor isn’t HTTP-based, your various .razor files don’t have access to the HttpContext object that is so important in other ASP.NET scenarios. It turns out you need HttpContext almost constantly while working with OIDC authentication. Based on non-Blazor ASP.NET, most developers will inject IHttpContextAccessor which does work – until you deploy the app, then it is null. Microsoft’s guidance when somebody raised an issue about this? “Don’t do that.” They left the guy hanging without a solution, and then a bot auto-closed the discussion. Just when I think they “get it” when it comes to open source and interacting with the public … but I digress.

The validation method should compare the current time to the ExpiresUtc property that was set during login. That property is part of the token data that is stored inside the cookie. Unfortunately you can only access cookie data through HttpContext, which isn’t available in Blazor-land. The lack of HttpContext is part of the reason the earlier article added the _HostAuthModel class. Adding another handler there provides the solution: we have to cache the information needed by the validator, but there is some groundwork to do before that can happen.

Caching Token Expiration

For my first pass, I built the cache into the validation class. More of the bad advice you’ll find is that the validator object should be registered as a singleton DI service. It seemed to work until I opened another browser and logged in under a different account. The first browser switched to that account. Since the validator inherits from AuthenticationStateProvider, and that class manages a single Identity, a new login overwrites a previous login’s Identity when you register it as a singleton. The solution was to register the cache as a simple singleton service, and separately register the validator as a scoped service. A scoped service’s lifetime matches the life of the HTTP request, and in the case of Blazor, the only HTTP request is to _Host.cshtml, which exists for the entire lifetime of the Blazor-side content.

I created the following simple data structure to hold the data we need to cache:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public class BlazorServerAuthData

{

public string SubjectId;

public DateTimeOffset Expiration;

public string AccessToken;

public string RefreshToken;

}

For the purposes of this article, we don’t actually need the access or refresh token information, but if you use API scopes to access headless services, having those in the cache will be handy. (I’ll probably write another article about that.) Also, it seems the validator could handle token refresh, although it isn’t clear to me yet if this is architecturally sound (so don’t quote me!).

The cache service is equally simple, wrapping a few bits of a ConcurrentDictionary keyed on the subject ID claim and storing the data object shown above:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

public class BlazorServerAuthStateCache

{

private ConcurrentDictionary<string, BlazorServerAuthData> Cache

= new ConcurrentDictionary<string, BlazorServerAuthData>();

public bool HasSubjectId(string subjectId)

=> Cache.ContainsKey(subjectId);

public void Add(string subjectId, DateTimeOffset expiration, string accessToken, string refreshToken)

{

var data = new BlazorServerAuthData

{

SubjectId = subjectId,

Expiration = expiration,

AccessToken = accessToken,

RefreshToken = refreshToken

};

Cache.AddOrUpdate(subjectId, data, (k, v) => data);

}

public BlazorServerAuthData Get(string subjectId)

{

Cache.TryGetValue(subjectId, out var data);

return data;

}

public void Remove(string subjectId)

{

Cache.TryRemove(subjectId, out _);

}

}

Finally, register it at the very end of ConfigureServices in Startup.cs:

1

services.AddSingleton<BlazorServerAuthStateCache>();

Populate the Cache

As explained earlier, we need the cache because the validator can’t directly use HttpContext to inspect the auth cookie. We need more code in _HostAuthModel to populate the cache. Let’s begin by injecting a reference to the cache singleton service:

1

2

3

4

5

6

public readonly BlazorServerAuthStateCache Cache;

public _HostAuthModel(BlazorServerAuthStateCache cache)

{

Cache = cache;

}

Originally I populated the cache using a redirect after the login challenge, but I quickly realized that doesn’t work for persistent authentication. If cold-start the application then navigate there with a persistent login cookie from an earlier session, the application recognizes your login but the validator doesn’t work – nothing is in the cache.

Fortunately, the default handler has everything it needs to populate the cache. The non-Blazor User.Identity also has an IsAuthenticated property, and when that is true, we grab the subject ID from the list of claims and check whether it has already been cached. If not, we populate the cache. Since the host only runs once, this is pretty efficient.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

public async Task<IActionResult> OnGet()

{

if (User.Identity.IsAuthenticated)

{

var sid = User.Claims

.Where(c => c.Type.Equals("sid"))

.Select(c => c.Value)

.FirstOrDefault();

if (sid != null && !Cache.HasSubjectId(sid))

{

var authResult = await HttpContext.AuthenticateAsync("oidc");

DateTimeOffset expiration = authResult.Properties.ExpiresUtc.Value;

string accessToken = await HttpContext.GetTokenAsync("access_token");

string refreshToken = await HttpContext.GetTokenAsync("refresh_token");

Cache.Add(sid, expiration, accessToken, refreshToken);

}

}

return Page();

}

At the end of the article, I’ll mention some additional code that goes here for real-world applications.

Now we’re ready to validate authentication states.

The Auth Validator

The validator needs access to our cached expiration data, and it also needs an instance of ILogger to pass to the base class:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public class BlazorServerAuthState

: RevalidatingServerAuthenticationStateProvider

{

private readonly BlazorServerAuthStateCache Cache;

public BlazorServerAuthState(

ILoggerFactory loggerFactory,

BlazorServerAuthStateCache cache)

: base(loggerFactory)

{

Cache = cache;

}

}

The required RevalidationInterval property is a TimeSpan. There is probably no “correct” interval for this, but one minute or even a few minutes seems reasonable, and it would be trivial to make this externally configurable. However, for development purposes, I set this to ten seconds so that I wasn’t waiting around to see if a particular code change worked as intended.

1

2

protected override TimeSpan RevalidationInterval

=> TimeSpan.FromSeconds(10); // TODO read from config

The real work is the ValidateAuthenticationStateAsync method. It returns true or false, indicating whether the auth state is still valid. We grab the subject ID from the AuthenticationState object passed into the method, find our expiration data in the cache, and do a simple comparison to the current time. If the login has expired, we remove the data from the cache and return false. That’s literally all it takes.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

protected override Task<bool> ValidateAuthenticationStateAsync(AuthenticationState authenticationState, CancellationToken cancellationToken)

{

var sid =

authenticationState.User.Claims

.Where(c => c.Type.Equals("sid"))

.Select(c => c.Value)

.FirstOrDefault();

if (sid != null && Cache.HasSubjectId(sid))

{

var data = Cache.Get(sid);

if(DateTimeOffset.UtcNow >= data.Expiration)

{

Cache.Remove(sid);

return Task.FromResult(false);

}

}

return Task.FromResult(true);

}

This does such a tiny amount of work, it didn’t seem important to test the cancellation token.

Finally, we go back to Startup.cs and register our validator, again at the very end of ConfigureServices (specifically, after the line where we register the cache):

1

2

services.AddSingleton<BlazorServerAuthStateCache>();

services.AddScoped<AuthenticationStateProvider, BlazorServerAuthState>();

First Test Run

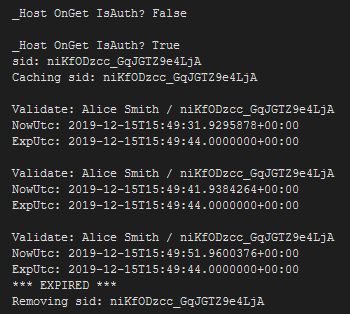

I added a bit of debug logging – something to show the result of the IsAuthenticated check in the _Host OnGet handler, and various bits of information about the caching and validation process. I also set the login ExpiresUtc to just 30 seconds so that I wouldn’t have to wait to see a five minute expiration in action. Here is the result using the IdentityServer demo site’s “alice” local account:

This was encouraging, but I noticed something a little strange: the Blazor UI didn’t respond to this. The login identity was gone, because the Index.razor page showed “Hello,” at the top (where an authenticated user name should appear), but I could still navigate to the various Razor component pages.

More Bad Advice

In the earlier article, I added some MVC authorization-policy code to Startup that looks like this:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

services.AddMvcCore(options =>

{

var policy = new AuthorizationPolicyBuilder()

.RequireAuthenticatedUser()

.Build();

options.Filters.Add(new AuthorizeFilter(policy));

});

In an MVC program, this will require authentication througout the application by default, and every reasonable-looking attempt I’ve found online to get OIDC working with Blazor includes that snippet. Unfortunately, it’s wrong, Blazor completely ignores this. You don’t need it. In a project like ours, it does apply the policy to the _Host.cshtml file because “real” Razor Pages live in MVC-land, but we disable that policy with an [AllowAnonymous] attribute, so it’s useless to us. Consequently, the [AllowAnonymous] attribute we added in the previous article is also not needed when the code above is removed.

The downside is that Blazor currently has no way to require authenticated users for every page, at least not officially. In theory, you have to add this to the top of every .razor page in a Blazor application:

1

@inject [Authorize]

Not ideal, to say the least.

(As an aside, I’ve always wondered why the attribute is “authorize” rather than “authenticate”. I suppose it’s a side effect of the policies being driven by authorizations (entitlements/permissions), but in general the use of each term seems a bit mixed up within the various class names and namespaces in .NET security overall.)

I did find a hack that seems to work: you can add the attribute just once in the _Imports.razor file instead, because it is applied to every page and component in the app. The file is intended to contain using statements, but it works.

Unfortunately the Blazor template’s reaction to de-authentication isn’t ideal either.

Second Test Run

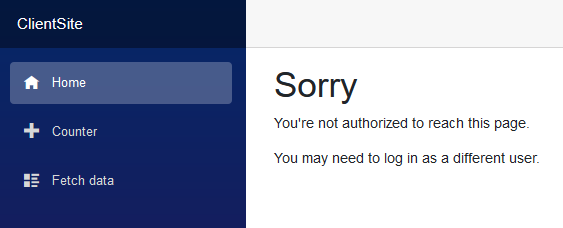

After adding [Authorize] to _Imports.razor and running the test again, when the validator expires the login, the UI immediately changes to show this… no navigation required:

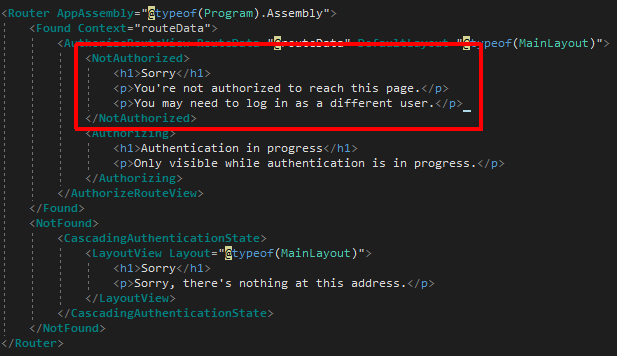

That comes from the <NotAuthorized> section of App.razor, which is wired up to the AuthenticationStateChanged event fired by the base class of our validation logic:

Fixing Automatic Logout

Look at the screenshot of the UI again carefully. Notice that only the Index.razor area shows the message, even though the [Authorize] attribute is in _Imports.razor which should apply everywhere. The sidebar navigation menu is still there and active because it’s part of MainLayout.razor which is external to <NotAuthorized>. I didn’t check whether the auth tags work further up the hierarchy because there is a bigger problem.

The user isn’t really logged out at this point. Like the January 2018 article about IdentityServer logout, only the user’s local login cookie is removed – the user is still logged in, as far as Identity Server is concerned.

We can kill two birds with one stone by changing the <NotAuthorized> section of App.razor:

1

2

3

4

5

@inject NavigationManager NavManager

<NotAuthorized>

@{ NavManager.NavigateTo("/Logoff", true); }

</NotAuthorized>

The second argument is forceLoad which sends the path to the browser without checking routing rules. Without it, we’d get the <NotFound> content from App.razor because the router would not recognize /Logoff, since it isn’t known in Blazor-land and Startup doesn’t define any MVC-style routing.

This way, when the de-authentication event fires, our user will be redirected to the _HostAuthModel logout handler, which both ensures a clean logout and replaces the entire UI with our anonymous-user content.

From a purely technical standpoint, we’re done.

Better UX

This demonstrates how to completely support and manage login timeouts, but this behavior isn’t great UX. The user will be working in the app, then BAM… logged out. No warning, no chance to save their work.

A user-friendly way of dealing with this depends heavily on your user base and the specifics of your application.

For my real application (an enterprise-style in-house line-of-business app), I know my users log out daily and that it’s ok to keep them logged in all day. We apply a 20-hour expiration, and there is additional code in the _HostAuthModel default handler that checks whether the user’s existing login is either from a previous day or within 2 hours of expiration, since our users are typically only in the application for sessions lasting less than one hour. If either rule applies, they’re redirected to the /Logout handler immediately, so that they begin using the app in a logged-out state.

For a public-facing site, it’s normal to have much longer persistent logins (days, weeks, even a full month). You might implement similar logic when the user is approaching login expiration – either force a logout on their initial visit, or present a warning with the option to login again (by first forcing logout when the user agrees to proceed).

Another option might be a custom Razor component added to App.razor to show a “save your work” popup warning based on a new event raised by the custom validator class when expiration is approaching.

Conclusion

These are early days for Blazor-based UI, and it’s amazing to see what Microsoft has accomplished in a very short period of time. However, it bothers me that something as critical as security is being handled so poorly, and that Microsoft team members seem dismissive of developers who are struggling to figure out how to do it correctly. Security is hard to do correctly even when it’s well supported, and OIDC / OAuth2 is arguably the most widely used standard auth scheme on the Internet today.

I hope these two articles help others who find themselves with a need to get this working.

Comments